No matter how cool you may have thought you were in high school, when you look at your yearbook a decade or more later you are likely to laugh, not just at yourself but also at all the other cool kids. That's because clothing styles and hairstyles change with time, making earlier styles laughable. Fashions change in other kinds of things, also, such as cars, furniture and architecture. One thing we don't usually think of as going out of fashion, however, is language, and yet it does.

Read something written 200 years ago and you are likely find that the past tense of swim was swimmed, not swam. The past tense of dig was digged, not dug. The past tense of hang was hanged, not hung. Today's those older past-tense verbs seem laughable. They are long out of fashion. If we could go back in time, proper English speakers would likely laugh at the way we talk.

Pronouns, too, change with the times. Today it is fashionable to use they as a singular pronoun, when our English teachers probably taught us to use either he or she, and when in doubt, use he. That was the fashion then. But if you read William Shakespeare and certain other writers from earlier times, you will find they used they as as singular pronoun, too. This is a fashion, like hemlines, that goes one way, then the other.

Reading a Jules Verne novel recently I was reminded once again that writers of his era, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, were fond of the word singular. Some people still use that word on occasion, but today we much prefer unique. The use of singular has simply gone out of fashion. So have the words thee and thou.

You may have heard of Strunk and White Elements of Style or the AP Stylebook. These are guides for English usage, the latter often used by journalists, the former by writers in general. The word style in these titles is suggestive of the fashionable nature of language. The writers of these guides are saying, in effect, there may be other ways of saying this, but this is the way we approve. This is what's fashionable here and now.

Wednesday, July 27, 2016

Monday, July 25, 2016

Of tea, plans and partners

There might have been no scientific connection between drinking tea and getting one's thoughts in order, but that was the way it seemed, at least in Mma Ramotswe's opinion. Tea brought about focus, and that helped.

I just finished my morning cup of tea, and now I am ready to start writing. So I understand Precious Ramotswe's point of view. Others swear by that mug of coffee in the morning. Others require a cigarette to achieve the focus they desire. For still others something else may be needed. I used to find that the 30-minute drive into work every morning prepared my brain for what lay ahead, just as the 30-minute drive home later cleared my mind and helped me escape work for the night.

So maybe it isn't tea or coffee or cigarettes or anything else that does the job, but simply the habit itself. Caffeine and nicotine may strengthen the habit, but perhaps it is just the routine, the sense of the familiar and comfortable that we need to focus our minds. For Mma Ramotswe and me, that means a cup of hot tea.

I am still in the early chapters of Alexander McCall Smith's The Handsome Man's Deluxe Cafe and already I've found three passages worth a comment. That was the first. Here is No. 2:

Mma Ramotswe slipped the business plan into a drawer. The trouble with plans, she thought, was that they tended to be expressions of hope. Everybody, it seemed, felt that they should have a plan, but for most people the plan merely said what they would like to happen rather than what they would actually achieve. Most people do what they wanted to do, whether or not that was what their plan said they should do.

Again I agree with Mma Ramotswe. I have never worried much about plans, whether career plans or financial plans or any other kind of plans. Right now I am vacationing in a Tennessee cabin, but do I have a vacation plan, other than a date to leave and go back home? No. That's what makes it a real vacation, as far as I'm concerned.

Nor have I ever cared for listing objectives or writing mission statements. I would hate when as a copy editor charged with building newspaper pages, I was told by management to state my objectives for the coming year. These had to be stated in numerical form for easy measurement and show improvement over the previous year's production. But if I designed x number of pages a day last year, do I really want to say I will do x+1 pages in the future? I was already doing my best. Was I supposed to sacrifice quality for quantity? No, I was more likely to be criticized for making errors than for being slow. So, like Mma Ramotswe, I "slipped the business plan into a drawer," metaphorically speaking, and went on doing what I had been doing.

Partner, though, had come to mean something else -- as Mma Ramotswe had read in a magazine -- and she felt a different word was needed.

So what do you call that person you are living with, especially if that person is of the same sex? The word partner seems to be the one that has been chosen, never mind the anxiety it has produced for lawyers, cops and many others who for years have had partners in a non-sexual sense? Mma Ramotswe is certainly is not alone in feeling the use of the term could now be misunderstood. Nowadays when a cowboy calls someone "pardner" in an old western movie, the audience is likely to giggle.

Alexander McCall Smith, The Handsome Man's Deluxe Cafe

I just finished my morning cup of tea, and now I am ready to start writing. So I understand Precious Ramotswe's point of view. Others swear by that mug of coffee in the morning. Others require a cigarette to achieve the focus they desire. For still others something else may be needed. I used to find that the 30-minute drive into work every morning prepared my brain for what lay ahead, just as the 30-minute drive home later cleared my mind and helped me escape work for the night.

So maybe it isn't tea or coffee or cigarettes or anything else that does the job, but simply the habit itself. Caffeine and nicotine may strengthen the habit, but perhaps it is just the routine, the sense of the familiar and comfortable that we need to focus our minds. For Mma Ramotswe and me, that means a cup of hot tea.

I am still in the early chapters of Alexander McCall Smith's The Handsome Man's Deluxe Cafe and already I've found three passages worth a comment. That was the first. Here is No. 2:

Mma Ramotswe slipped the business plan into a drawer. The trouble with plans, she thought, was that they tended to be expressions of hope. Everybody, it seemed, felt that they should have a plan, but for most people the plan merely said what they would like to happen rather than what they would actually achieve. Most people do what they wanted to do, whether or not that was what their plan said they should do.

Again I agree with Mma Ramotswe. I have never worried much about plans, whether career plans or financial plans or any other kind of plans. Right now I am vacationing in a Tennessee cabin, but do I have a vacation plan, other than a date to leave and go back home? No. That's what makes it a real vacation, as far as I'm concerned.

Nor have I ever cared for listing objectives or writing mission statements. I would hate when as a copy editor charged with building newspaper pages, I was told by management to state my objectives for the coming year. These had to be stated in numerical form for easy measurement and show improvement over the previous year's production. But if I designed x number of pages a day last year, do I really want to say I will do x+1 pages in the future? I was already doing my best. Was I supposed to sacrifice quality for quantity? No, I was more likely to be criticized for making errors than for being slow. So, like Mma Ramotswe, I "slipped the business plan into a drawer," metaphorically speaking, and went on doing what I had been doing.

Partner, though, had come to mean something else -- as Mma Ramotswe had read in a magazine -- and she felt a different word was needed.

So what do you call that person you are living with, especially if that person is of the same sex? The word partner seems to be the one that has been chosen, never mind the anxiety it has produced for lawyers, cops and many others who for years have had partners in a non-sexual sense? Mma Ramotswe is certainly is not alone in feeling the use of the term could now be misunderstood. Nowadays when a cowboy calls someone "pardner" in an old western movie, the audience is likely to giggle.

Thursday, July 21, 2016

Making up words

Barbara Wallraff calls it "recreational word coining," that practice of making up new words just for fun. It sounds like something that could use a new word.

I suspect that most of us play this game whether we realize it or not, sometimes just making up new words on the spot. Families often have their own unique words for things that you won't find in any dictionary. When I tell my wife I am going rest-roaming, she knows I am off in search of a restroom in an unfamiliar restaurant, mall or whatever. I have never heard anyone else use that word and never expect to.

Several books have been dedicated to recreational word coining, including Wallraff's own Word Fugitives. In a column she writes for The Atlantic Monthly, she asks readers to suggest new words for something that doesn't have a word but should. Her book collects some of the best suggestions.

Shouldn't there be a word for choosing the slowest-moving line in a grocery store or fast-food restaurant? Among the best suggestions are misqueue and misalinement. The trouble is we already have the words miscue and misalignment. The suggested words are clever puns, but they probably have no staying power as words.

How about a word to describe trying to avoid someone, like an ex-spouse, who happens to be in the same room? Among the suggestions are snear miss, snubterfuge and can't-standoffish. Again clever puns and not much else.

Similarly, fridgety was suggested as a word to describe when you repeatedly look into the refrigerator, more because of restlessness than hunger. Numblers seems like a good term for people who recite their phone numbers so quickly on answering machines that you can't hope to remember them. And virtuecrat nicely describes those people, in the words of Joseph Eptein who coined it, "whose sense of their own high virtue derives from their nauseatingly enlightened political opinions." Don't you know such people?

Such words are amusing, but will they ever find their way into a dictionary? Sometimes they do, as with scofflaw and couch potato, but usually they don't. To gain wide acceptance, new words must fill a need and must be repeated often enough that others will remember them and use them themselves. According to Allan Metcalf, author of Predicting New Words, new words should look old. They should give the impression they've been around for awhile, but we just haven't noticed them. Some words like snubterfuge and fridgety are just too clever. We couldn't have missed them.

I suspect that most of us play this game whether we realize it or not, sometimes just making up new words on the spot. Families often have their own unique words for things that you won't find in any dictionary. When I tell my wife I am going rest-roaming, she knows I am off in search of a restroom in an unfamiliar restaurant, mall or whatever. I have never heard anyone else use that word and never expect to.

Several books have been dedicated to recreational word coining, including Wallraff's own Word Fugitives. In a column she writes for The Atlantic Monthly, she asks readers to suggest new words for something that doesn't have a word but should. Her book collects some of the best suggestions.

Shouldn't there be a word for choosing the slowest-moving line in a grocery store or fast-food restaurant? Among the best suggestions are misqueue and misalinement. The trouble is we already have the words miscue and misalignment. The suggested words are clever puns, but they probably have no staying power as words.

How about a word to describe trying to avoid someone, like an ex-spouse, who happens to be in the same room? Among the suggestions are snear miss, snubterfuge and can't-standoffish. Again clever puns and not much else.

Similarly, fridgety was suggested as a word to describe when you repeatedly look into the refrigerator, more because of restlessness than hunger. Numblers seems like a good term for people who recite their phone numbers so quickly on answering machines that you can't hope to remember them. And virtuecrat nicely describes those people, in the words of Joseph Eptein who coined it, "whose sense of their own high virtue derives from their nauseatingly enlightened political opinions." Don't you know such people?

Such words are amusing, but will they ever find their way into a dictionary? Sometimes they do, as with scofflaw and couch potato, but usually they don't. To gain wide acceptance, new words must fill a need and must be repeated often enough that others will remember them and use them themselves. According to Allan Metcalf, author of Predicting New Words, new words should look old. They should give the impression they've been around for awhile, but we just haven't noticed them. Some words like snubterfuge and fridgety are just too clever. We couldn't have missed them.

Wednesday, July 20, 2016

A collective activity

"Literature," I went on, "has always been a collective activity. Writers adapting plots from other writers, sharing ideas and characters and images, all the way back to Homer. Shakespeare didn't invent a single one of his plots. You have nothing to be ashamed of."

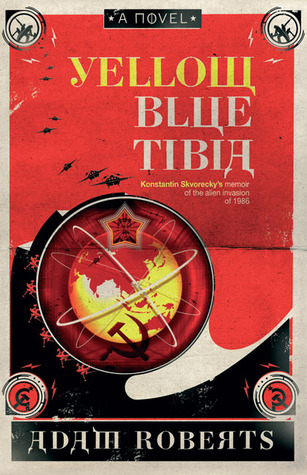

The speaker in the Adam Roberts novel quoted above is one Soviet science fiction writer talking to another who has just admitted most of his books have just been rewrites, little more than Russian translations, of books by western writers. Yellow Blue Tibia is a humorous novel, and this passage is intended to be amusing. Yet it does contain a germ of truth. Writing, perhaps the most solitary of occupations, is, in at least three senses, "a collective activity."

1. Writers, as the Adam Roberts character suggests, do feed off other writers. Plots, character types, metaphors and styles are imitated or recycled again and again. As I mentioned once before here, I congratulated Mark Winegardner on his novel Crooked River Burning, which I said reminded me of John Dos Passos. My comment must have surprised him, as his reply surprised me. He said he had been reading Dos Passos before writing the novel. He had, whether deliberately or not, imitated another writer's style.

Later Winegardner wrote one or more of those Godfather novels, using characters and plot lines developed by the late Mario Puzo. And so, while plagiarism may be wrong, writers do borrow from other writers all the time.

2. Wes Anderson quotes Austrian writer Stefan Zweig in the screenplay for his film The Grand Budapest Hotel, "It is an extremely common mistake: people think the writer's imagination is always at work, that he is constantly inventing an endless supply of incidents and episodes, that he simply dreams up his stories out of thin air. In point of fact, the opposite is true. Once the public knows you are a writer, they bring the characters and events to you -- and as long as you maintain your ability to look and carefully listen, these stories will continue to seek you out."

Perhaps some ideas do originate entirely in the author's mind, but usually ideas come from a variety of sources -- other writers (as mentioned above), experiences, newspapers, magazines, television, stories told by friends and acquaintances, etc. -- and are then mulled over in the writer's mind until they are ready to emerge in an entirely original form. Writers may need to be alone to write, but if they are too alone they will have nothing to write about.

3. Finally, writers need readers. I met Mark Winegardner at the Buckeye Book Fair held each November in Wooster, Ohio. Similar events are held throughout the country to introduce authors to readers in hopes some of those readers will buy their books. Authors and publishers depend on book events, including book signings, to sell copies. Not all writers can support themselves with their writing. Whether they can or not depends on readers. Their work, after all, is a collective activity.

Adam Roberts, Yellow Blue Tibia

The speaker in the Adam Roberts novel quoted above is one Soviet science fiction writer talking to another who has just admitted most of his books have just been rewrites, little more than Russian translations, of books by western writers. Yellow Blue Tibia is a humorous novel, and this passage is intended to be amusing. Yet it does contain a germ of truth. Writing, perhaps the most solitary of occupations, is, in at least three senses, "a collective activity."

|

| Mark Winegardner |

Later Winegardner wrote one or more of those Godfather novels, using characters and plot lines developed by the late Mario Puzo. And so, while plagiarism may be wrong, writers do borrow from other writers all the time.

2. Wes Anderson quotes Austrian writer Stefan Zweig in the screenplay for his film The Grand Budapest Hotel, "It is an extremely common mistake: people think the writer's imagination is always at work, that he is constantly inventing an endless supply of incidents and episodes, that he simply dreams up his stories out of thin air. In point of fact, the opposite is true. Once the public knows you are a writer, they bring the characters and events to you -- and as long as you maintain your ability to look and carefully listen, these stories will continue to seek you out."

Perhaps some ideas do originate entirely in the author's mind, but usually ideas come from a variety of sources -- other writers (as mentioned above), experiences, newspapers, magazines, television, stories told by friends and acquaintances, etc. -- and are then mulled over in the writer's mind until they are ready to emerge in an entirely original form. Writers may need to be alone to write, but if they are too alone they will have nothing to write about.

3. Finally, writers need readers. I met Mark Winegardner at the Buckeye Book Fair held each November in Wooster, Ohio. Similar events are held throughout the country to introduce authors to readers in hopes some of those readers will buy their books. Authors and publishers depend on book events, including book signings, to sell copies. Not all writers can support themselves with their writing. Whether they can or not depends on readers. Their work, after all, is a collective activity.

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

Grace under pressure

In the same way that a badly adjusted set of binoculars gives you two overlapping images, the two McCains don't come together for me. It must be frustrating for his handlers to be be unable -- due to some internal blockage in the candidate -- to get the amiable self onstage instead of the less palatable one who shows up for debates and now hollered speeches.

My beloved granddaughter has played soccer almost from the time she could run. This fall she will begin playing for her Pennsylvania high school team. A few days ago my son, her father, told me how beautifully she played in a recent scrimmage. He lamented that she rarely played that well in actual games when she knew people were watching and any mistake on her part could be costly. As Dick Cavett similarly laments about presidential candidate John McCain in 2008, this young soccer player "gives you two overlapping images."

As a newspaper journalist, and especially as an editorial page editor for so many years, I got to know many politicians, and I observed that McCain was not alone in seeming one way when campaigning for votes, or newspaper endorsements, and another way in more casual circumstances. In fact, many of us, probably most of us, behave differently under pressure. Some students know the material but do badly on tests. People can speak effortlessly in small groups but freeze up if asked to give a speech to a crowd. I have observed that even beauty contestants often look so much better after the pageant is over. Their smiles are no longer forced, their gestures no longer posed. They become real women again.

Newspaper deadlines force reporters to write under under pressure, sometimes great pressure. I did it for many years, but I never felt I did my best writing under such circumstances. I thought I did better with my weekly column when I had days to write and rewrite.

All this brings me around to Mike Royko, the great Chicago columnist, who turned out five pieces a week, mostly for the Chicago Daily News. I recently started reading One More Time, a collection of his best columns published in 1999 after his widow and several friends sorted through the nearly 8,000 columns he wrote. "Considering the gems Mike regularly wrote, selecting the best was not an easy job," said Judy Royko, his widow.

My newspaper often used Royko 's column on our op-ed page, so I got to read many of them. They were always good, and even though they were mostly about Chicago, they still informed and entertained readers in Ohio. And to think, Royko wrote five columns a week, or one column each working day. From experience I know the difficulty of writing just one column a week. The pressure of doing five a week seems unbearable. Yet Royko did it, and did it well, for many years. There are some of us who can do our best even when the heat is on.

Dick Cavett, Talk Show

My beloved granddaughter has played soccer almost from the time she could run. This fall she will begin playing for her Pennsylvania high school team. A few days ago my son, her father, told me how beautifully she played in a recent scrimmage. He lamented that she rarely played that well in actual games when she knew people were watching and any mistake on her part could be costly. As Dick Cavett similarly laments about presidential candidate John McCain in 2008, this young soccer player "gives you two overlapping images."

As a newspaper journalist, and especially as an editorial page editor for so many years, I got to know many politicians, and I observed that McCain was not alone in seeming one way when campaigning for votes, or newspaper endorsements, and another way in more casual circumstances. In fact, many of us, probably most of us, behave differently under pressure. Some students know the material but do badly on tests. People can speak effortlessly in small groups but freeze up if asked to give a speech to a crowd. I have observed that even beauty contestants often look so much better after the pageant is over. Their smiles are no longer forced, their gestures no longer posed. They become real women again.

| Mike Royko |

All this brings me around to Mike Royko, the great Chicago columnist, who turned out five pieces a week, mostly for the Chicago Daily News. I recently started reading One More Time, a collection of his best columns published in 1999 after his widow and several friends sorted through the nearly 8,000 columns he wrote. "Considering the gems Mike regularly wrote, selecting the best was not an easy job," said Judy Royko, his widow.

My newspaper often used Royko 's column on our op-ed page, so I got to read many of them. They were always good, and even though they were mostly about Chicago, they still informed and entertained readers in Ohio. And to think, Royko wrote five columns a week, or one column each working day. From experience I know the difficulty of writing just one column a week. The pressure of doing five a week seems unbearable. Yet Royko did it, and did it well, for many years. There are some of us who can do our best even when the heat is on.

Friday, July 15, 2016

When sci-fi comes true

Combine Joseph Heller dialogue with a Kurt Vonnegut Jr. plot and you might get something like Adam Roberts's brilliant 2009 novel Yellow Blue Tibia.

Funnier than any story about an alien invasion, nuclear disaster and KGB assassins has any right to be, the novel starts wacky and keeps getting wackier. It begins after the close of World War II when Stalin gathers together some of the best Soviet science fiction writers and orders them to come up with a plot about an invasion from outer space. They concoct a wild story about "radiation aliens" who attack the Ukraine. Stalin likes it, files it away and swears them all to secrecy.

Years later during the winter of 1985-86, one of those writers, Konstantin Skvorecky, now an old man who works as a translator, is approached by another survivor from that strange writing project and told that their plot is all coming true. The aliens have invaded exactly as they described in their story.

Soon, pursued by the KGB, Skvorecky is taking a wild taxi ride to the Chernobyl nuclear plant with a former nuclear scientist, now a cab driver with an extreme fear of being touched by another man, and a fat American woman, a Scientologist, with whom he falls in love. They are trying to prevent the disaster they fear is coming before the KGB can catch up with them.

So is there an alien invasion or not? And is this novel science fiction or not? One must read to the end to find the answers.

Funnier than any story about an alien invasion, nuclear disaster and KGB assassins has any right to be, the novel starts wacky and keeps getting wackier. It begins after the close of World War II when Stalin gathers together some of the best Soviet science fiction writers and orders them to come up with a plot about an invasion from outer space. They concoct a wild story about "radiation aliens" who attack the Ukraine. Stalin likes it, files it away and swears them all to secrecy.

Years later during the winter of 1985-86, one of those writers, Konstantin Skvorecky, now an old man who works as a translator, is approached by another survivor from that strange writing project and told that their plot is all coming true. The aliens have invaded exactly as they described in their story.

Soon, pursued by the KGB, Skvorecky is taking a wild taxi ride to the Chernobyl nuclear plant with a former nuclear scientist, now a cab driver with an extreme fear of being touched by another man, and a fat American woman, a Scientologist, with whom he falls in love. They are trying to prevent the disaster they fear is coming before the KGB can catch up with them.

So is there an alien invasion or not? And is this novel science fiction or not? One must read to the end to find the answers.

Wednesday, July 13, 2016

Adventure at sea

Sometimes the third time really is the charm. So it is with Alistair Maclean and me. I missed McLean entirely during his heyday when he was one of the world's most popular writers of thrillers, yet I had heard so many good things about his books that I finally decided to give them a try. The first two novels I read, Partisans and Puppet on a Chain, proved disappointing. My third attempt, however, produced different results.

San Andreas, published in 1984, is a World War II adventure that takes place entirely aboard a hospital ship in the North Atlantic in winter. Hospital ships, marked with big red crosses, are supposedly neutral, yet the Germans seem determined to stop, if not sink, the San Andreas. One or more saboteurs aboard keep destroying navigational equipment, while planes and submarines attack with relatively light arms, suggesting they want to do damage, but not too much damage. So what's going on?

When the ship's captain is badly wounded in one attack, the responsibility for getting the San Andeas to safety falls on Archie McKinnon, the bosun. The hospital ship has no weapons aboard, so McKinnon must defend the ship using the bad weather, the long winter nights and the ship itself. Then there are the problems of finding the saboteurs(s) and getting the ship to a friendly port.

McKinnon turns out to be my kind of hero, one who uses brains more than brawn, and the result proves thoroughly entertaining. San Andreas may be the name of a California fault line, but McLean's novel with that title turned out to be nothing like a disaster.

San Andreas, published in 1984, is a World War II adventure that takes place entirely aboard a hospital ship in the North Atlantic in winter. Hospital ships, marked with big red crosses, are supposedly neutral, yet the Germans seem determined to stop, if not sink, the San Andreas. One or more saboteurs aboard keep destroying navigational equipment, while planes and submarines attack with relatively light arms, suggesting they want to do damage, but not too much damage. So what's going on?

When the ship's captain is badly wounded in one attack, the responsibility for getting the San Andeas to safety falls on Archie McKinnon, the bosun. The hospital ship has no weapons aboard, so McKinnon must defend the ship using the bad weather, the long winter nights and the ship itself. Then there are the problems of finding the saboteurs(s) and getting the ship to a friendly port.

McKinnon turns out to be my kind of hero, one who uses brains more than brawn, and the result proves thoroughly entertaining. San Andreas may be the name of a California fault line, but McLean's novel with that title turned out to be nothing like a disaster.

Tuesday, July 12, 2016

Dubbed

Another word is accolade, originally from a French word meaning to embrace. The English used the word to refer to the bestowal of knighthood. Now almost any type of award or expression of approval can be called an accolade..

To take knighthood away from someone is termed degradation, a word now used in the fields of chemistry and geology, as well as when anyone or anything declines in condition or quality.

Thursday, July 7, 2016

Some like it again and again and again

Yes, the anniversary was a few years ago, but the book, like the movie, doesn't show its age. This is a coffee-table book, one that house guests are almost guaranteed to want to pick up and leaf through. It's filled with photos, both movie stills and publicity shots, plus a number of behind-the-scenes photographs you are unlikely to find anywhere else. Maslon also tosses in some choice excerpts from the script, photo copies of documents showing Monroe's frequent tardiness and absences from the set and other assorted goodies. He devotes an entire chapter to the various efforts to put Some Like It Hot on television and the stage over the years. An attempted sitcom never survived beyond the pilot.

For my money, the book's best feature is a two-page essay called, for some reason, "Spills, Thrills, a Laughs, and Games." Once you get past that silly title, the essay provides some fascinating insights into why this movie turned out to be as good as it is, other than those reasons already mentioned above. For example, it defies categorization. Is it a screwball comedy, a buddy picture, a gangster movie, a sex farce or a romantic comedy. Well, yes to all those. Just when you think it's one thing, it becomes something else.

Maslon's points out how the Wilder-Diamond script frequently recycles bits of dialogue for comic effect, such as when Joe and Jerry (Curtis and Lemmon) claim to have attended the Sheboygan Conservatory of Music, and later Sugar (Monroe), also trying to make a good impression, says she attended the same fictional school. Maslon's essay helped me enjoy the movie all the more when I watched it the other night.

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

Had Lincoln survived

Imagine that Abraham Lincoln survived John Wilkes Booth's assassination attempt but that Vice President Andrew Johnson, also a target of the plot that night, had been killed. Further imagine that it was then Lincoln, not Johnson, who was impeached by Congress during the political struggle over Reconstruction following the Civil War. This is what Stephen L. Carter imagines in his terrific 2012 novel The Impeachment of Abraham Lincoln.

Carter goes on to imagine that a brilliant and beautiful young black woman, fresh out of Oberlin College, becomes a part of Lincoln's legal defense team, albeit a lowly clerk responsible more for sweeping floors than determining legal strategy. Still Abigail Canner becomes central to the story, and what an exciting story it is.

The author paints a Congress in 1867 not so different from Congress today, a group of individuals more interested in political gain than anything else. With Johnson dead, the president pro tempore of the Senate is next in line to be president, yet it is the Senate that must vote on removing the president from office. Meanwhile several others, including Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, who presides over the impeachment trial, also have political ambitions that might benefit from Lincoln's departure. Clearly the deck is stacked against the president.

Carter gives us a riveting political thriller, legal thriller and, after the head of the defense team is found murdered in front of a brothel in the company of a black woman, crime thriller. Yet there are flaws. The impeachment of Lincoln proves easier to believe than certain other parts of the plot, such as that other members of Abigail's family also play important roles in the story. And the author leaves too many questions unanswered.

The novel leaves us with at least two conclusions about history. One is that even if Lincoln had survived Booth's attempt on his life, the aftermath of the war would have proceeded pretty much as it did. The other is that one thing that might have been different is our perception of Abraham Lincoln. Had Lincoln been caught in the middle of the Reconstruction fight, perhaps his historical reputation would have suffered, just as President John F. Kennedy's standing in history might have suffered had he not been assassinated.

Carter goes on to imagine that a brilliant and beautiful young black woman, fresh out of Oberlin College, becomes a part of Lincoln's legal defense team, albeit a lowly clerk responsible more for sweeping floors than determining legal strategy. Still Abigail Canner becomes central to the story, and what an exciting story it is.

The author paints a Congress in 1867 not so different from Congress today, a group of individuals more interested in political gain than anything else. With Johnson dead, the president pro tempore of the Senate is next in line to be president, yet it is the Senate that must vote on removing the president from office. Meanwhile several others, including Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, who presides over the impeachment trial, also have political ambitions that might benefit from Lincoln's departure. Clearly the deck is stacked against the president.

The novel leaves us with at least two conclusions about history. One is that even if Lincoln had survived Booth's attempt on his life, the aftermath of the war would have proceeded pretty much as it did. The other is that one thing that might have been different is our perception of Abraham Lincoln. Had Lincoln been caught in the middle of the Reconstruction fight, perhaps his historical reputation would have suffered, just as President John F. Kennedy's standing in history might have suffered had he not been assassinated.

Monday, July 4, 2016

Very different brains

"Yes," said Piglet, "Rabbit has Brain."

There was a long silence.

"I suppose," said Pooh, "that that's why he never understands anything."

A.A. Milne fills his Winnie-the-Pooh books with references to brains. Christopher Robin has the best one, and he is the one the other characters always turn to when they are really stumped. Owl, like Rabbit, has a brain, and earns respect because he can spell his own name, even if he does spell it WOL, and he can even "spell Tuesday so that you knew it wasn't Wednesday." Others of them just have fluff in their heads, we are told, and Pooh himself is "a Bear of Very Little Brain."

Yet Pooh writes songs, which he calls Hums, Tigger can bounce better than anyone else and Kanga is an excellent mother to Roo. Each character in the stories contributes something, and none of them can do everything. At one time or another, each depends on others in their group.

I don't watch many current television series, but I have become a belated fan of both The Big Bang Theory and Bones, and I have enjoyed Scorpion since the first episode. Each of these series, like others of recent vintage like Monk and the many variations on the Sherlock Holmes stories, features one or more characters with exceptional brains but who are deficient in social skills or are unable to understand such things as irony or sarcasm. On episodes of Bones, I've heard characters say things like, "I don't know what that means," "I'm not good with metaphor" and "that's slang, right?" The geniuses in these shows always have friends with more average brains to help them understand things their more powerful brains cannot grasp.

In one Calvin and Hobbes panel, Calvin defends himself after screwing up a class project by saying, "Some of us are too smart for the class." When a classmate scoffs, he adds, "You know how Einstein got bad grades as a kid? Well, mine are even worse!" Calvin is right about one thing. His brain does work differently than other brains, and in his own way, he is a genius.

A friend of mine was in an Eeyore kind of mood one day, a bit down on herself, and she said, "Nobody else seems to think the same way I do." "Nobody does," I told her. "That's why you are necessary."

There was a long silence.

"I suppose," said Pooh, "that that's why he never understands anything."

A.A. Milne, The House at Pooh Corner

Yet Pooh writes songs, which he calls Hums, Tigger can bounce better than anyone else and Kanga is an excellent mother to Roo. Each character in the stories contributes something, and none of them can do everything. At one time or another, each depends on others in their group.

I don't watch many current television series, but I have become a belated fan of both The Big Bang Theory and Bones, and I have enjoyed Scorpion since the first episode. Each of these series, like others of recent vintage like Monk and the many variations on the Sherlock Holmes stories, features one or more characters with exceptional brains but who are deficient in social skills or are unable to understand such things as irony or sarcasm. On episodes of Bones, I've heard characters say things like, "I don't know what that means," "I'm not good with metaphor" and "that's slang, right?" The geniuses in these shows always have friends with more average brains to help them understand things their more powerful brains cannot grasp.

In one Calvin and Hobbes panel, Calvin defends himself after screwing up a class project by saying, "Some of us are too smart for the class." When a classmate scoffs, he adds, "You know how Einstein got bad grades as a kid? Well, mine are even worse!" Calvin is right about one thing. His brain does work differently than other brains, and in his own way, he is a genius.

A friend of mine was in an Eeyore kind of mood one day, a bit down on herself, and she said, "Nobody else seems to think the same way I do." "Nobody does," I told her. "That's why you are necessary."

Friday, July 1, 2016

Dated title

When I read George Orwell's Nineteen Eight-Four in the early Sixties, the year 1984 still seemed far in the future. More than three decades after 1984, Orwell's novel is still being read, yet I wonder if its impact has somehow declined as 1984 has faded into the past. Has his choice of a title, plus the passage of time, turned a futuristic novel into, at least in some readers' minds, a historical novel?

This thought follows from my post of two days ago about time-related words like modern and new. You might also include the words contemporary, present, now, current, today, yesterday and tomorrow, among others. The passage of time can change the meaning of these words to the reader. In a similar way, dates mentioned in stories, especially in stories set in the future, can make those stories seem dated as time passes.

When setting a story in some future time, it might be wise to keep that time ambiguous, or at least put it far enough in the future that it will be a very long time before that future becomes past. When Orwell's novel was published in 1949, he probably didn't imagine people would still be reading it in the 21st century.

In the late Nineties I read a novel about the terrible things that happen on Jan 1, 2000, when the world's computers fail. I doubt anyone bothered to read that novel after that date, when nothing terrible happened at all.

Before Orwell wrote his visionary novel, Aldous Huxley wrote Brave New World, a book to which Nineteen Eight-Four is often compared. I don't think Huxley wrote the better book, but I do think he chose the better title. Brave New World will always suggest the future, something Nineteen Eight-Four can never do again.

This thought follows from my post of two days ago about time-related words like modern and new. You might also include the words contemporary, present, now, current, today, yesterday and tomorrow, among others. The passage of time can change the meaning of these words to the reader. In a similar way, dates mentioned in stories, especially in stories set in the future, can make those stories seem dated as time passes.

When setting a story in some future time, it might be wise to keep that time ambiguous, or at least put it far enough in the future that it will be a very long time before that future becomes past. When Orwell's novel was published in 1949, he probably didn't imagine people would still be reading it in the 21st century.

In the late Nineties I read a novel about the terrible things that happen on Jan 1, 2000, when the world's computers fail. I doubt anyone bothered to read that novel after that date, when nothing terrible happened at all.

Before Orwell wrote his visionary novel, Aldous Huxley wrote Brave New World, a book to which Nineteen Eight-Four is often compared. I don't think Huxley wrote the better book, but I do think he chose the better title. Brave New World will always suggest the future, something Nineteen Eight-Four can never do again.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)