In a scene in the movie Foreign Letters, a recent immigrant to the United States from Israel expresses to her husband her amazement that in America to be called a Jew is considered offensive, while to be called Jewish is perfectly acceptable. I, too, have noticed this odd distinction, and like the woman in the film, I don't understand it either.

That are other distinctions that are equally curious. It is, for example, considered offensive to refer to "colored people," while "people of color" is proper. To anyone who has lived in this country for a few decades, it will be clear why one of these phrases contains cultural baggage the other does not, but imagine how confusing this must be to a relative newcomer.

I noticed the Census Bureau has decided to stop using the word Negro, long after most others stopped using it. I don't know why Negro should be offensive, but it is to many people, so it's best to avoid it. Most people prefer black or African-American, even though many black persons are neither black nor Americans (nor Africans).

Similarly, Asian is considered proper, while Oriental is not. For some strange reason, it is wrong to refer to a person's race, but OK to refer to the geographical origin of that race. This is true, even though not all Asians are Oriental, and not all Africans are Negro.

White people don't seem to mind being called Caucasian, although I've noticed that white people are routinely referred to as Europeans in Canada. The fact that they may have never been within 1,000 miles of Europe makes no difference.

Native Americans is now the common way to refer to American Indians. This has always annoyed me because the word native refers to one's birth. I was born in Ohio, thus I am both a native Ohioan and a native American, even though my ancestors came from Europe. Even "native Americans" originally came from somewhere else, so they are really no more native than I am. Their families just came before mine did, just like the Mayflower families came before mine did.

All these unwritten rules about how one should and should not refer to people must be very confusing to immigrants. They are confusing to me, and I'm a native.

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Monday, February 25, 2013

Not a pudd'nhead

Yet there is something about the novel that never seems to grow stale: the triumph of the underdog. We all love underdogs, whether in sports or in stories. The appeal of television detectives like Monk and Columbo lies, to a great extent, in the fact that they seem like such unlikely heroes. The killers always make a mistake when they underestimate them. In the same way, when we watch reruns of The Andy Griffith Show, some of our favorite episodes are those in which, whether because of Andy's intervention or dumb luck, hapless Barney Fife comes out the hero. Twain has this sort of thing going for him in Pudd'nhead Wilson.

When Wilson comes to this Mississippi River town, he promptly wins the nickname Pudd'nhead when he makes a witticism that his hearers do not understand as wit. It doesn't help that he collects the fingerprints of townspeople, a foolish hobby in the eyes of others, or that he has never practiced law, even though he was trained it. For most of the story, Wilson is just a minor character, an underdog waiting in the wings.

The main plot has to do with Roxy, a slave woman who is mostly white. Her baby son is even more white than she is and, in fact, looks just like her master's infant son. So, to save her son from slavery, she switches the two babies. Years later after the murder of a prominent man, Pudd'nhead is called on to defend the accused. Of course, Wilson's interest in fingerprinting proves to be the key to discovering what really happened that night, as well as to exposing Roxy's long-ago deception.

Much about this novel, including Twain's use of language, will disturb today's readers, but the triumph of the underdog will, as ever, bring satisfaction.

Friday, February 22, 2013

Second-rate second edition

1. To add new information.

2. To correct errors.

In both of these respects, the second edition of The U.S. Women's Soccer Team: An American Success Story by Clemente A. Lisi is a disappointment. To be sure, the first edition of the book, published in 2010, has been updated in the 2013 version. Lisi, a reporter for the New York Post, adds coverage of the team through the 2012 Olympics. Yet this new chapter seems hurriedly written and will not satisfy anyone who remembers the Americans' gold medal victory and might hope for something more than what was read in newspaper coverage last summer.

And while parts of the book have been updated, other parts have not been. In his introduction, Lisi writes, "Women's Professional Soccer hopes to pick up where the Women's United Soccer Association left off -- and, this time, succeed. The jury is still out on what the outcome will be and whether the league will be a viable, moneymaking operation." On page 147, he reports that Women's Professional Soccer folded in 2012.

On page 77, we are told Christine Lilly "remains an active member of the squad." On the very next page, we read that she retired in 2010.

As for typos, there are more than you would expect in a second edition (or even a first edition, for that matter). Lisi describes a "hunderbolt shot" and writes about "brining Solo back." Writing about the 2004 Olympics, he says, "Germany could have forced a penalty-kick shootout had Renate Lingor's free kick slid wide of Scurry's goal." Surely there should be a not in there somewhere.

The book reads like a collection of excerpts from press clippings, which is exactly what it is to judge from the notes at the end of each chapter. Only occasionally does Lisi dig below the surface, as when he analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of the team's various coaches.

This is a book that will appeal only to the most diehard fans of women's soccer. I happen to be one of these, so I read it with interest, albeit also with disappointment.

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Almost human

- The dog's name and number were once listed in the Los Angeles telephone directory.

- He earned more for his movies than human actors did, once making $1,000 a week for a silent picture when the lead human actor made only $150.

- Rin Tin Tin was named a co-respondent in a divorce case, a position normally taken by the other woman.

- In Academy Awards voting one year, Rin Tin Tin got the most votes in the Best Actor category, although Emil Jannings was eventually given the Oscar.

Rin Tin Tin's entire story is an amazing one, starting with his discovery, along with other puppies, on a French battlefield at the close of World War I by Lee Duncan, an American soldier. Duncan brought the dog home with him at the end of the war, trained him and eventually turned him into one of the biggest stars of the silent era in Hollywood. Decades later, one of his descendants using the same name became a huge star in a popular television series (although other dogs actually appeared on the screen).

Yet Orlean's book is not just the story of a famous dog. It is also the story of the less famous people behind the dog, including Duncan, who made Rin Tin Tin the center of his life; Bert Leonard, a colorful Hollywood producer responsible for The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin on television in the 1950s (he also produced Route 66 and Naked City); and Janniettia Brodsgaard and Daphne Hereford, two Texas women responsible for keeping Rin Tin Tin's breeding line alive.

Of course, to that list must now be added the name of Susan Orlean, whose long research and excellent story-telling ability have brought Rin Tin Tin back into the public eye.

Friday, February 15, 2013

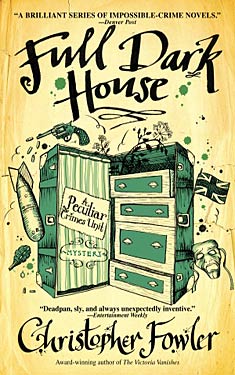

Peculiar crimes

Christopher Fowler's 2003 mystery novel Full Dark House, the first in his series of books featuring the unconventional detectives Arthur Bryant and John May, begins with Bryant's death in an explosion. Killing off one of the heroes in the first chapter of the first book hardly seems like the way to start a series, but in Full Dark House, as in presumably the novels that follow, the unusual becomes the expected.

Christopher Fowler's 2003 mystery novel Full Dark House, the first in his series of books featuring the unconventional detectives Arthur Bryant and John May, begins with Bryant's death in an explosion. Killing off one of the heroes in the first chapter of the first book hardly seems like the way to start a series, but in Full Dark House, as in presumably the novels that follow, the unusual becomes the expected.May, an old man as story opens, is determined to discover who killed his partner, and he suspects it has something to do with their very first case together, some 60 years previously, when the two very young men are put in charge of the Peculiar Crimes Unit of Scotland Yard. They would seem to be the intended scapegoats for crimes too difficult for more experienced police officers to solve.

The 1940 case involves an apparent phantom of the opera, a strange creature who picks off members of the cast of a new London musical production and then disappears, seemingly through walls. These murders continue even after Bryant and May are on the scene, virtually witnesses to the crimes they are supposed to be solving.

Every few chapters we return to the 21st century and May's investigation of his eccentric partner's death. How these very peculiar crimes, including a dancers who disappears from a locked room, are solved and everything set right again makes for amusing and suspenseful reading, and I am looking forward to reading some other Bryant and May adventures.

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Spelling is secondary

Before we came to Florida for the winter, my wife, Linda, volunteered a couple times a week in a second-grade class at Taft Elementary School in Ashland, Ohio. A few days ago, she received an envelope full of handmade valentines from these second-graders. Here are a few excerpts from the notes they wrote on these valentines:

"I can't waite to see you."

"Have a nice treip."

"You are the best techer ever."

"Thanks for the neacklits (necklaces). I loved them."

"You are so luky to be up thear in florda in the nice worm sunny Breezy weather and get to go to the beach and swim in that nice cold water and I am haveing a great time in school."

"I am so happy about you that u are having a good time on your vaction."

"I am coat up now because of you!"

"We miss you so much we hop you are having a great vackashan."

"I miss you so much and you are so lukcy."

"You are the best techer ever day You are cute.

"Hope you have a wounderfull time thair."

"How is it up in florda? thank you for helping us on all our work."

I chose these lines from the pupils' letters not to make fun of their writing, but rather to applaud them for being willing to write what was on their minds and in their hearts despite not yet knowing enough about spelling, punctuation, grammar or geography to do it perfectly. I also applaud their teacher, Sally Carr, for leaving her red pen capped and not giving the letters back to the kids to do over. These are, after all, not school papers or even business letters, but personal notes. We all get a little sloppy in personal notes, e-mail and, especially text messages. It's not a crime.

There was a time a few centuries ago, before dictionaries helped standardize spelling, when everyone, even the most educated people, wrote pretty much the way these children wrote their letters. They knew what the words sounded like, and they just guessed how they should be spelled. William Shakespeare, still considered the greatest writer in English ever, apparently didn't even know how to spell his own name. In the existing signatures, Shakespeare twice abbreviated his name as Shakp and Shakspe. Other times he signed it Shaksper, Shakspere and Shakspeare, never Shakespeare.

Robert Recorde is the person credited with devising the equals sign (=) in 1557. He explained his reasoning thusly: "bicause noe .2. thynges, can be moare equalle." We can understand what Robert Recorde wrote, and we can understand our second-graders, too. Good spelling is important, but not as important as having something to say and then getting it down on paper.

"I can't waite to see you."

"Have a nice treip."

"You are the best techer ever."

"Thanks for the neacklits (necklaces). I loved them."

"You are so luky to be up thear in florda in the nice worm sunny Breezy weather and get to go to the beach and swim in that nice cold water and I am haveing a great time in school."

"I am so happy about you that u are having a good time on your vaction."

"I am coat up now because of you!"

"We miss you so much we hop you are having a great vackashan."

"I miss you so much and you are so lukcy."

"You are the best techer ever day You are cute.

"Hope you have a wounderfull time thair."

"How is it up in florda? thank you for helping us on all our work."

I chose these lines from the pupils' letters not to make fun of their writing, but rather to applaud them for being willing to write what was on their minds and in their hearts despite not yet knowing enough about spelling, punctuation, grammar or geography to do it perfectly. I also applaud their teacher, Sally Carr, for leaving her red pen capped and not giving the letters back to the kids to do over. These are, after all, not school papers or even business letters, but personal notes. We all get a little sloppy in personal notes, e-mail and, especially text messages. It's not a crime.

There was a time a few centuries ago, before dictionaries helped standardize spelling, when everyone, even the most educated people, wrote pretty much the way these children wrote their letters. They knew what the words sounded like, and they just guessed how they should be spelled. William Shakespeare, still considered the greatest writer in English ever, apparently didn't even know how to spell his own name. In the existing signatures, Shakespeare twice abbreviated his name as Shakp and Shakspe. Other times he signed it Shaksper, Shakspere and Shakspeare, never Shakespeare.

Robert Recorde is the person credited with devising the equals sign (=) in 1557. He explained his reasoning thusly: "bicause noe .2. thynges, can be moare equalle." We can understand what Robert Recorde wrote, and we can understand our second-graders, too. Good spelling is important, but not as important as having something to say and then getting it down on paper.

Monday, February 11, 2013

Book learnin'

Here are some language-related items I picked up from my recent reading:

Oslo: Harry Hole, the protagonist in Jo Nesbø's crime novel Nemesis, explains the origins of Norway's capital city's name to a visitor, "The 'Os' of Oslo means 'ridge,' the hillside we're sitting on now. Ekeberg Ridge. And 'lo' is the plain you can see down there."

Thus, Oslo means simply ridge-plain. Quite a number of place names, like River Road or Lakeville, are little more than descriptions of local geography. These names sound much more exotic in another language. Cuyahoga, an Iroquois word, means nothing more than "crooked river." Most rivers are crooked, however, so Clevelanders are probably happy to with Cuyahoga River.

Inner wear: Ever notice that we wear underwear and outerwear? Why not innerwear and outerwear or underwear and overwear? In Victorian London, Liza Picard informs us that in Victorian times they did speak of inner wear. Somehow this more logical term got lost over time.

The whole nine yards: This common expression, which became the title of an amusing Bruce Willis movie several years ago, basically just means "the whole thing." Writing in his Dwight D. Eisenhower biography, Ike: An American Hero, Michael Korda says the phrase dates only from World War II. The belts of .50-caliber ammunition for the machine guns on American bombers were 27-feet long. When gunners had fired "the whole nine yards," it was time to reload.

Oslo: Harry Hole, the protagonist in Jo Nesbø's crime novel Nemesis, explains the origins of Norway's capital city's name to a visitor, "The 'Os' of Oslo means 'ridge,' the hillside we're sitting on now. Ekeberg Ridge. And 'lo' is the plain you can see down there."

Thus, Oslo means simply ridge-plain. Quite a number of place names, like River Road or Lakeville, are little more than descriptions of local geography. These names sound much more exotic in another language. Cuyahoga, an Iroquois word, means nothing more than "crooked river." Most rivers are crooked, however, so Clevelanders are probably happy to with Cuyahoga River.

Inner wear: Ever notice that we wear underwear and outerwear? Why not innerwear and outerwear or underwear and overwear? In Victorian London, Liza Picard informs us that in Victorian times they did speak of inner wear. Somehow this more logical term got lost over time.

The whole nine yards: This common expression, which became the title of an amusing Bruce Willis movie several years ago, basically just means "the whole thing." Writing in his Dwight D. Eisenhower biography, Ike: An American Hero, Michael Korda says the phrase dates only from World War II. The belts of .50-caliber ammunition for the machine guns on American bombers were 27-feet long. When gunners had fired "the whole nine yards," it was time to reload.

Friday, February 8, 2013

Not a beginner's novel

Aaron, perhaps because of his physical handicaps, is a prickly young man, the sort of person who takes offense at just about anything anyone says to him. When he marries Dorothy, a plump physician who lacks what her patients might term "a good bedside manner," their marriage is filled with little spats over little things. Interestingly, when she appears to Aaron periodically after her death, the spats continue. They both have trouble showing, not to mention telling, how much each means to the other.

With his older sister, Aaron runs a publishing house that specializes in vanity titles, books that authors pay to have published, but also puts out an endless series of "Beginner's" books on the order of "Idiot's Guides." This provides us with the title of Tyler's novel, which basically just repeats the eternal truth that, if you have something to say to those you love, do it while they are still alive.

If there is not quite as much depth here as one finds in most Tyler novels, The Beginner's Goodbye is still an excellent story, skillfully told, that is likely to be remembered long after the final page is read.

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

Mysteries of the north

Northern Europe seems to be a hotbed for mystery novels, mostly of the hard-boiled variety. The books by Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo (Sweden) have been popular since the 1960s. Henning Mankell (Sweden) became widely known for his Kurt Wallander novels in the 1990s. More recently Stieg Larsson, also from Sweden, has written international bestsellers.

In addition, one can now find English translations of novels by K.O. Dahl (Norway), Håkan Nesser (Sweden), Ysra Sigurðardóttir (Iceland), Camilla Läckberg (Sweden), Jan Kjærstad (Norway), Åsa Larsson (Sweden), Åke Edwardson (Sweden), Arnaldur Indriðason (Iceland), Karin Fossum (Norway), Anne Holt (Norway), Gunnar Staalesen (Norway), Mari Jungsted (Sweden), Jørn Lier Horst (Norway), Jan Arnald (Sweden), Karin Alvtegen (Sweden), Helene Tursten (Sweden), Inger Frimansson (Sweden), Johan Theorin (Sweden), Unni Maria Lindell (Norway), Andrey Yuryevich Kurkov (Ukraine), and probably a few others I haven't heard about.

In addition, one can now find English translations of novels by K.O. Dahl (Norway), Håkan Nesser (Sweden), Ysra Sigurðardóttir (Iceland), Camilla Läckberg (Sweden), Jan Kjærstad (Norway), Åsa Larsson (Sweden), Åke Edwardson (Sweden), Arnaldur Indriðason (Iceland), Karin Fossum (Norway), Anne Holt (Norway), Gunnar Staalesen (Norway), Mari Jungsted (Sweden), Jørn Lier Horst (Norway), Jan Arnald (Sweden), Karin Alvtegen (Sweden), Helene Tursten (Sweden), Inger Frimansson (Sweden), Johan Theorin (Sweden), Unni Maria Lindell (Norway), Andrey Yuryevich Kurkov (Ukraine), and probably a few others I haven't heard about.

Recently I've been reading two mysteries from that part of the world, The Princess of Burundi by Kjell Eriksson, set in Sweden, and Nemesis by Jo Nesbø, set in Norway. They are both pretty good, although I found the former easier to enjoy. Eriksson's novel is about the torture and murder of an unemployed family man, a former low-level criminal, with a passion for tropical fish. Nesbø begins with a bank robbery that leaves a woman dead but few clues about the identity of the killer.

Eriksson has no major character. Rather the mystery is solved by various officers in the police department, including a woman on maternity leave who just can't stop herself from becoming involved in the case. Nemesis, on the other hand, has the more traditional single hero, even if Harry Hole himself is hardly traditional. Hole is an alcoholic police officer who manages to keep his job only because he is a much better detective than anyone else on the force.

Unfortunately, Hole wakes up in a stupor one morning and discovers that the woman he thinks he may have spent the night with is dead, an apparent suicide. He doesn't think she killed herself, and he tries to discover what really happened without making himself a suspect in a murder case.

Much of Nemesis seems a little hard to swallow, and Harry Hole isn't a particularly likeable character. I found The Princess of Burundi (I love the title, considering it's a story set in Sweden) more rewarding.

Recently I've been reading two mysteries from that part of the world, The Princess of Burundi by Kjell Eriksson, set in Sweden, and Nemesis by Jo Nesbø, set in Norway. They are both pretty good, although I found the former easier to enjoy. Eriksson's novel is about the torture and murder of an unemployed family man, a former low-level criminal, with a passion for tropical fish. Nesbø begins with a bank robbery that leaves a woman dead but few clues about the identity of the killer.

Eriksson has no major character. Rather the mystery is solved by various officers in the police department, including a woman on maternity leave who just can't stop herself from becoming involved in the case. Nemesis, on the other hand, has the more traditional single hero, even if Harry Hole himself is hardly traditional. Hole is an alcoholic police officer who manages to keep his job only because he is a much better detective than anyone else on the force.

Unfortunately, Hole wakes up in a stupor one morning and discovers that the woman he thinks he may have spent the night with is dead, an apparent suicide. He doesn't think she killed herself, and he tries to discover what really happened without making himself a suspect in a murder case.

Much of Nemesis seems a little hard to swallow, and Harry Hole isn't a particularly likeable character. I found The Princess of Burundi (I love the title, considering it's a story set in Sweden) more rewarding.

Monday, February 4, 2013

Smarter than we think

Animals are smarter than we think. More to the point, they are smarter than scientists think, or at least most scientists until just a few years ago. Science writer Virginia Morell probes the question of just how surprisingly smart animals are in her book Animal Wise.

For years science told us animals don't really think, they just act according to instinct. Animals don't feel pain or experience emotions, they said. These were the same scientists who insisted man had evolved and was thus biologically related to animals, and yet somehow people had thoughts and feelings and mental capabilities way beyond that of animals.

Jane Goodall and her study of chimpanzees had a lot to do with changing the way science views animals. She had relatively little scientific education before she began observing chimpanzees in the wild, and this turned out to be an advantage. She broke all the rules because she didn't know what the rules were. She gave names to her subjects. She wrote about them as individuals with their own personalities. She referred to them as he or she, not it. She observed and reported chimpanzees making and using tools when everyone else in the scientific community believed only humans could do this. At first, her work was pooh-poohed by the scientific community, but eventually she made converts. Today many other scientists are studying various species in much the way Goodall did and making surprising discoveries in the process.

Morell visited many of these scientists and describes their work in her book, which is written more for the average reader than for scientists. She tells why some researchers think parrots name their children, why others are convinced fish feel pain when they have hooks in their mouths, how it is known that bowerbirds have an artistic sense and how it was discovered that some dogs can learn new words in much the same way children do, and much more. She writes about studies involving ants, birds, rats, elephants, dolphins, chimpanzees, dogs and wolves, and in each case the findings are astounding.

Some scientists are still not convinced, but we amateurs with pets won't have as much trouble with Morell's book.

House cats love looking out windows, and one day I noticed my cat staring for a long time at the only basement window in our house with a ledge where he might sit and look out, but the window was high and out of easy reach. The next day, as I watched the TV that was just a few feet from the window, I saw my cat climb onto the TV and position himself to leap from it to the window ledge. I held my breath because it looked to me like a risky jump. Apparently the cat decided the same thing because he eventually turned around and jumped down to the floor.

A day or two later I noticed my cat on the window ledge, looking outside. Further observation showed me he had gotten there the best possible way. He first jumped onto the wood box and from there leaped to the fireplace mantel. After crossing that, it was just a short leap to the ledge. A small child could have figured out these steps in a matter of seconds. It took my cat several days, but he figured it out. He solved the problem. He used his mind.

For years science told us animals don't really think, they just act according to instinct. Animals don't feel pain or experience emotions, they said. These were the same scientists who insisted man had evolved and was thus biologically related to animals, and yet somehow people had thoughts and feelings and mental capabilities way beyond that of animals.

Jane Goodall and her study of chimpanzees had a lot to do with changing the way science views animals. She had relatively little scientific education before she began observing chimpanzees in the wild, and this turned out to be an advantage. She broke all the rules because she didn't know what the rules were. She gave names to her subjects. She wrote about them as individuals with their own personalities. She referred to them as he or she, not it. She observed and reported chimpanzees making and using tools when everyone else in the scientific community believed only humans could do this. At first, her work was pooh-poohed by the scientific community, but eventually she made converts. Today many other scientists are studying various species in much the way Goodall did and making surprising discoveries in the process.

Morell visited many of these scientists and describes their work in her book, which is written more for the average reader than for scientists. She tells why some researchers think parrots name their children, why others are convinced fish feel pain when they have hooks in their mouths, how it is known that bowerbirds have an artistic sense and how it was discovered that some dogs can learn new words in much the same way children do, and much more. She writes about studies involving ants, birds, rats, elephants, dolphins, chimpanzees, dogs and wolves, and in each case the findings are astounding.

Some scientists are still not convinced, but we amateurs with pets won't have as much trouble with Morell's book.

House cats love looking out windows, and one day I noticed my cat staring for a long time at the only basement window in our house with a ledge where he might sit and look out, but the window was high and out of easy reach. The next day, as I watched the TV that was just a few feet from the window, I saw my cat climb onto the TV and position himself to leap from it to the window ledge. I held my breath because it looked to me like a risky jump. Apparently the cat decided the same thing because he eventually turned around and jumped down to the floor.

A day or two later I noticed my cat on the window ledge, looking outside. Further observation showed me he had gotten there the best possible way. He first jumped onto the wood box and from there leaped to the fireplace mantel. After crossing that, it was just a short leap to the ledge. A small child could have figured out these steps in a matter of seconds. It took my cat several days, but he figured it out. He solved the problem. He used his mind.

Friday, February 1, 2013

On senior-citizen time

When we make reference to time we are, in most cases, talking nonsense. Consider the following statements:

"I'll be with you in a moment."

"It's been an eternity since I've seen her."

"I want you to pick up your toys this instant."

"Let's get together soon."

In all these statements, the time reference is, at best, an exaggeration and, at worst, an absurdity. Both a moment and an instant are gone by the time the sentence is finished. Eternity -- can there be more than one of them? -- is certainly longer than one lifetime, let alone the months or years that have passed between encounters between two people. The word soon, at least, is ambiguous enough to mean anything from a few minutes from now to never.

And what does now mean? Mark Forsyth writes in his book The Etymologicon, "These days, now has to have the word right stuck on the front or it doesn't mean a thing." For that matter, what does these days mean?

For the most part, ambiguity in our time references is fine with us. In fact, it is, in most instances, exactly what we want. We don't want to have to be too specific about when something will happen or when something happened. We seem to understand what other people mean even when they talk nonsense.

I must say, however, that I am having trouble adjusting to what I think of as senior-citizen time here in Florida, where I am spending the winter. I have always tried to be prompt. If I was supposed to start work at 6 a.m., I arrived at work as close to 6 a.m. as I possibly could. I never wanted to arrive "fashionably late" to parties. According to senior-citizen time, however, prompt means early and on time means late.

I have twice gone to men's breakfasts at a restaurant that are announced for 7 a.m. Both times I got there just before 7 to find everyone else seated, and it was obvious most of the men had been there for some time. I was regarded as a late-comer. My wife and I attend church dinners that are supposed to start at 5:45, but most people are seated and already eating their salads by 5:30. So it is obvious that even a specific time can be meaningless.

"I'll be with you in a moment."

"It's been an eternity since I've seen her."

"I want you to pick up your toys this instant."

"Let's get together soon."

In all these statements, the time reference is, at best, an exaggeration and, at worst, an absurdity. Both a moment and an instant are gone by the time the sentence is finished. Eternity -- can there be more than one of them? -- is certainly longer than one lifetime, let alone the months or years that have passed between encounters between two people. The word soon, at least, is ambiguous enough to mean anything from a few minutes from now to never.

And what does now mean? Mark Forsyth writes in his book The Etymologicon, "These days, now has to have the word right stuck on the front or it doesn't mean a thing." For that matter, what does these days mean?

For the most part, ambiguity in our time references is fine with us. In fact, it is, in most instances, exactly what we want. We don't want to have to be too specific about when something will happen or when something happened. We seem to understand what other people mean even when they talk nonsense.

I must say, however, that I am having trouble adjusting to what I think of as senior-citizen time here in Florida, where I am spending the winter. I have always tried to be prompt. If I was supposed to start work at 6 a.m., I arrived at work as close to 6 a.m. as I possibly could. I never wanted to arrive "fashionably late" to parties. According to senior-citizen time, however, prompt means early and on time means late.

I have twice gone to men's breakfasts at a restaurant that are announced for 7 a.m. Both times I got there just before 7 to find everyone else seated, and it was obvious most of the men had been there for some time. I was regarded as a late-comer. My wife and I attend church dinners that are supposed to start at 5:45, but most people are seated and already eating their salads by 5:30. So it is obvious that even a specific time can be meaningless.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)