Something about the 1998 film The Big Lebowski inspires not just repeated viewings but repeated books about the film. I finished reading another one of them a couple days ago, namely The Big Lebowski: An Illustrated, Annotated History of the Greatest Cult Film of All Time by Jenny M. Jones. Just in my personal library I find The Big Lebowski:The Making of a Coen Brothers Film, I'm a Lebowski, You're a Lebowski: Life, The Big Lebowski, and What Have You, Two Gentlemen of Lebowski, The Dude Abides: The Gospel According to the Coen Brothers, The Coen Brothers: The Life of the Mind and Coen Brothers. The latter three books discuss Coen a Brothers films in general. And a few nights ago I watched the movie yet again. Maybe that's what makes a cult film: it's one you just can't get enough of.

Like The Wizard of Oz and It's a Wonderful Life, among others, The Big Lebowski was not a hit when it was first released. Critics panned it. Moviegoers ignored it. I'm proud to say I got it the first the first time I saw it with my son in a south Pittsburgh theater, although I'm not at all certain why I liked it as much as I did. It has many things I don't normally like in movies, including loads of f-words and Jeff Bridges. But I loved The Big Lebowski from the first, and still do.

The Jones book, suitable for Christmas gifts and coffee tables, is a gem, filled with discussions of just about anything you might want to know about the movie, plus lots of illustrations.

Is The Big Lebowski a detective story, a western, a musical, a sports movie or an offbeat comedy. Jones answers yes to all these questions. She views it as a remake of The Big Sleep, The Searchers and even The Wizard of Oz. The Wizard of Oz? I guess I'll just have to watch it again.

Thursday, October 29, 2015

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

It's a scandal

My first experience with a shopping mall came in the 1950s at the Westgate Shopping Center in Toledo. It still exists, at least as recently as a couple of years ago, but today it seems little more than a strip mall. Back in my youth, however, going to that mall with my family was a very big deal. The first McDonald's I ever saw was located nearby, which doubled the excitement of a trip to Westgate.

Back then the malls in many cities seemed to have a "gate" in their names -- Westgate, Northgate, etc., depending upon which end of town they were located. That practice ended in the early 1970s with Watergate, the biggest political scandal in American history. The scandal was named after the hotel where the breakin occurred that started the whole thing. A second Watergate scandal nearly occurred in the late 1970s when I spent a night at the hotel when I was in Washington for some briefings at the state department. I ordered a pheasant dinner in the Watergate's fanciest restaurant. In my very first bite of rice I felt something hard and spit it back out onto my plate. It was broken glass. I found other pieces of broken glass in the rice. Fortunately I didn't swallow any. Some people get pheasant under glass. I got glass under pheasant. At least it resulted in a free meal, plus a good story.

The Watergate Hotel, so called because it is located along the Potomac River, still exists. The scandal may have even been good for business. Not so for shopping malls, however. They don't want their names to sound like another scandal, for nowadays virtually every scandal, large or small, has a "gate" at the end. The New England Patriots have their Deflategate, Hillary Clinton has her Emailgate and Chris Christie had his Bridgegate. We have also heard Filegate, Nannygate, Pardongate, Troopergate, Weinergate, Bountygate, Rathergate and dozens of others. The gate suffix seems to be as popular in other countries as it is in the U.S. Britain had its Camillagate, Australia had its Choppergate, Finland had its Iraqgate and Sweden had its own Nannygate, and there are many others.

Centuries ago some English prisons had the gate suffix, namely Newgate and Ludgate. Before that walled cities had gates, and those gates had names. Way back then, a "gate" in a name meant an actual gate. Imagine that.

Back then the malls in many cities seemed to have a "gate" in their names -- Westgate, Northgate, etc., depending upon which end of town they were located. That practice ended in the early 1970s with Watergate, the biggest political scandal in American history. The scandal was named after the hotel where the breakin occurred that started the whole thing. A second Watergate scandal nearly occurred in the late 1970s when I spent a night at the hotel when I was in Washington for some briefings at the state department. I ordered a pheasant dinner in the Watergate's fanciest restaurant. In my very first bite of rice I felt something hard and spit it back out onto my plate. It was broken glass. I found other pieces of broken glass in the rice. Fortunately I didn't swallow any. Some people get pheasant under glass. I got glass under pheasant. At least it resulted in a free meal, plus a good story.

The Watergate Hotel, so called because it is located along the Potomac River, still exists. The scandal may have even been good for business. Not so for shopping malls, however. They don't want their names to sound like another scandal, for nowadays virtually every scandal, large or small, has a "gate" at the end. The New England Patriots have their Deflategate, Hillary Clinton has her Emailgate and Chris Christie had his Bridgegate. We have also heard Filegate, Nannygate, Pardongate, Troopergate, Weinergate, Bountygate, Rathergate and dozens of others. The gate suffix seems to be as popular in other countries as it is in the U.S. Britain had its Camillagate, Australia had its Choppergate, Finland had its Iraqgate and Sweden had its own Nannygate, and there are many others.

Centuries ago some English prisons had the gate suffix, namely Newgate and Ludgate. Before that walled cities had gates, and those gates had names. Way back then, a "gate" in a name meant an actual gate. Imagine that.

Monday, October 26, 2015

Woolf words vs. Wodehouse words

It should surprise no one that P.G. Wodehouse used different words (and words differently) in his novels than Virginia Woolf did in hers. They were, after all, very different writers. Even so, a study of the two writers' use of words, reported by Vivian Cook in It's All in a Word, makes fascinating reading.

In a typical Wodehouse novel, Cook writes, the word girl appears an average of once every 869 words. In written English in general, that word appears just once out of every 3,942 words. In a Woolf novel, girl shows up once every 2,865 words. The reason for this is that a Wodehouse novel usually involves a young man's difficulties in love with a young woman, and in Wodehouse's world, a young, unmarried woman is always called a girl. Woolf sometimes referred to young women as girls, too, but her books are not the light-hearted romantic romps that Wodehouse's are, so the words appears much less often.

Also, Cook says, the Woolf novel The Voyage uses 9,542 different words, twice as many as are found in Wodehouse's My Man Jeeves. Nothing shocking here. Woolf wrote more challenging books for more sophisticated readers. Of course they employ a much larger vocabulary.

Also, Cook says, the Woolf novel The Voyage uses 9,542 different words, twice as many as are found in Wodehouse's My Man Jeeves. Nothing shocking here. Woolf wrote more challenging books for more sophisticated readers. Of course they employ a much larger vocabulary.

Cook goes on to say, "P.G. Wodehouse uses absolutely and pretty ten times as often, boy eight times as often, girl five times as often and old 3.5 times as often. In reverse Virginia Woolf uses people and Mrs. nine times more often, men and women five times more often and world four times more often."

Cook wonders, too, why Wodehouse uses the pronoun I three times as often as Woolf. "Is it just that his characters spend their time in light badinage about each other or is it a more profound aspect of their worldviews?" Or is it because Wodehouse often wrote in first person?

At one time literary critics didn't concern themselves with questions like these. Thanks to the computer, however, they have, for better or worse, so much more to talk about.

In a typical Wodehouse novel, Cook writes, the word girl appears an average of once every 869 words. In written English in general, that word appears just once out of every 3,942 words. In a Woolf novel, girl shows up once every 2,865 words. The reason for this is that a Wodehouse novel usually involves a young man's difficulties in love with a young woman, and in Wodehouse's world, a young, unmarried woman is always called a girl. Woolf sometimes referred to young women as girls, too, but her books are not the light-hearted romantic romps that Wodehouse's are, so the words appears much less often.

Also, Cook says, the Woolf novel The Voyage uses 9,542 different words, twice as many as are found in Wodehouse's My Man Jeeves. Nothing shocking here. Woolf wrote more challenging books for more sophisticated readers. Of course they employ a much larger vocabulary.

Also, Cook says, the Woolf novel The Voyage uses 9,542 different words, twice as many as are found in Wodehouse's My Man Jeeves. Nothing shocking here. Woolf wrote more challenging books for more sophisticated readers. Of course they employ a much larger vocabulary.Cook goes on to say, "P.G. Wodehouse uses absolutely and pretty ten times as often, boy eight times as often, girl five times as often and old 3.5 times as often. In reverse Virginia Woolf uses people and Mrs. nine times more often, men and women five times more often and world four times more often."

Cook wonders, too, why Wodehouse uses the pronoun I three times as often as Woolf. "Is it just that his characters spend their time in light badinage about each other or is it a more profound aspect of their worldviews?" Or is it because Wodehouse often wrote in first person?

At one time literary critics didn't concern themselves with questions like these. Thanks to the computer, however, they have, for better or worse, so much more to talk about.

Friday, October 23, 2015

Where an alley isn't an alley

British linguist Vivian Cook writes in It's All in a Word about the many words the British have for alleyway, depending mostly on where in Great Britain you happen to be. Up north it can be a snicket. Down south it's a lane. (I can recall eating a wonderful meal in a tiny Thai restaurant along Maiden Lane in London a decade ago.) It's called a twitchell in Nottingham, a ginnel inYorkshire, a drangway in Gower, a folley in Colchester, a jetty in the East Midlands, a jigger in Merseyside, a shut in Shropshire, a stair in Edinburgh, a fennel or close elsewhere in Scotland, a pass in Northern Ireland and a by-passage or lead in other places. Until about 200 years ago, it might have been called a frescade.

That may be less confusing than the many words Americans have for street, sometimes all in the same town. It can also be termed a drive, avenue, boulevard, lane, road, terrace, circle, way, court and a few other imaginative choices.

I live on a short one-block street that at one time was called an avenue on the street sign at one end and something else, maybe a drive, at the other end. Then we got a letter from the post office advising everyone that it was officially a road. A road, to me, suggests something rural and something a little longer than a block, but a road it is, although much of the mail we get is still addressed to an avenue.

That may be less confusing than the many words Americans have for street, sometimes all in the same town. It can also be termed a drive, avenue, boulevard, lane, road, terrace, circle, way, court and a few other imaginative choices.

I live on a short one-block street that at one time was called an avenue on the street sign at one end and something else, maybe a drive, at the other end. Then we got a letter from the post office advising everyone that it was officially a road. A road, to me, suggests something rural and something a little longer than a block, but a road it is, although much of the mail we get is still addressed to an avenue.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

The art on your mail

There is fine art you place on your wall, but there is also fine art you place on your mail. Not being able to afford much of the former, I collect the latter, especially postage stamps relating to literature.

A few American stamps honor libraries or reading in general.Two stamps in my collection feature the Library of Congress, and a 1982 stamp honors American libraries, "Legacies to Mankind." Then there's a 1984 stamp showing Abraham Lincoln, his son, Tad, and a book. The stamp is dedicated to "A Nation of Readers."

Other stamps portray particular books or even characters from books. In 1993 the U.S. Postal Service issued 29-cent stamps honoring four classics in juvenile fiction: Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Little House on the Prairie, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Little Women, with imagined scenes from each of these books on the stamps. A couple of years ago my wife's cousin, whose mother came from Australia, gave me five Australian stamps, issued in 1985, that honor classic children's books from Australia, none of which I had ever heard of. They are Elves & Fairies, The Magic Pudding, Ginger Meggs, Blinky Bill and Snugglepot Cuddlepie.

Mostly however the postage stamps in my collection honor American authors. The postal service seems to issue at least one or two of these stamps every year. Among my favorites are those for Ernest Hemingway, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ogden Nash, Flannery O'Connor, Katherine Anne Porter, Ayn Rand, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Robert Penn Warren and Thornton Wilder. Each of these stamps is just a pleasure to look at. Most of them show an image representing the author's most famous work. O'Connor, who was known for raising peacocks, has peacock feathers on her stamp.

Other nations issue stamps honoring their own best writers. I have, for example, French stamps honoring Victor Hugo, Emile Zola and Albert Camus, as well as a Colombian stamp with Gabriel Garcia Marquez on its face.

A very few authors seem to be claimed by the whole world. I have, for example, stamps from the U.S., Italy and the Soviet Union honoring William Shakespeare, who lived in England. The Soviets also issued a stamp in 1960 showing Mark Twain.

I'd like to see more literary postage stamps being issued, but I'm grateful for the beauties we have.

A few American stamps honor libraries or reading in general.Two stamps in my collection feature the Library of Congress, and a 1982 stamp honors American libraries, "Legacies to Mankind." Then there's a 1984 stamp showing Abraham Lincoln, his son, Tad, and a book. The stamp is dedicated to "A Nation of Readers."

Other stamps portray particular books or even characters from books. In 1993 the U.S. Postal Service issued 29-cent stamps honoring four classics in juvenile fiction: Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Little House on the Prairie, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Little Women, with imagined scenes from each of these books on the stamps. A couple of years ago my wife's cousin, whose mother came from Australia, gave me five Australian stamps, issued in 1985, that honor classic children's books from Australia, none of which I had ever heard of. They are Elves & Fairies, The Magic Pudding, Ginger Meggs, Blinky Bill and Snugglepot Cuddlepie.

Mostly however the postage stamps in my collection honor American authors. The postal service seems to issue at least one or two of these stamps every year. Among my favorites are those for Ernest Hemingway, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ogden Nash, Flannery O'Connor, Katherine Anne Porter, Ayn Rand, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Robert Penn Warren and Thornton Wilder. Each of these stamps is just a pleasure to look at. Most of them show an image representing the author's most famous work. O'Connor, who was known for raising peacocks, has peacock feathers on her stamp.

Other nations issue stamps honoring their own best writers. I have, for example, French stamps honoring Victor Hugo, Emile Zola and Albert Camus, as well as a Colombian stamp with Gabriel Garcia Marquez on its face.

A very few authors seem to be claimed by the whole world. I have, for example, stamps from the U.S., Italy and the Soviet Union honoring William Shakespeare, who lived in England. The Soviets also issued a stamp in 1960 showing Mark Twain.

I'd like to see more literary postage stamps being issued, but I'm grateful for the beauties we have.

Monday, October 19, 2015

Jackson on the writing life

Private Demons, Judy Oppenheimer's biography of Shirley Jackson that I wrote about here a few days ago, includes some noteworthy comments about the writing life. Here are a few:

Many original, creative people have had the experience of being unpopular in high school.

This is true, of course, not just of budding writers but of teenagers gifted at just about anything other than football and basketball. Partly this may be due to the fact that creative people often tend to be introverts, who are rarely popular, in high school or elsewhere, whatever their natural talents. I am reminded of something Travis Hugh Culley wrote in his memoir A Comedy & A Tragedy. He attended a high school for students gifted in music, art and performance, and he recalls "a thin line ... between being original and being 'a problem.'" Thus creative teens may have difficulty fitting in even when they are surrounded by other creative teens.

Baking a cake was creative, too, after a fashion. You took the ingredients, combined them, and ended up with a product. Not so different from clothespin dolls or short stories, after all.

That reminded me of a blog post I wrote comparing writing with cooking, the blending of ingredients to create something new. A cherry pie is more than just cherries, just flour, just sugar, etc., Blended together and baked, it becomes a new creation. One baker's pie will be different from another baker's pie. In the same way writing involves blending ingredients from different sources, baked in the writer's mind with that writer's own experiences, creating something entirely original.

Throughout her life, Shirley loved the writing of a much earlier age -- Jane Austen, Samuel Richardson, Fanny Burney. These writers "give no sense of being hurried or pressed for unique ideas; they are peaceful and gracious and write with an infinite sense of leisure that I envy greatly," she wrote once.

If you are reading a thriller, "an infinite sense of leisure" is probably not what you want in a writer. "Get on with it," you want to shout whenever there is a break in the action. Yet many of our best writers, including Shirley Jackson, write with an unhurried, easy grace that hides how much work may have gone into each sentence. Or in Jackson's case, her style disguises how quickly she wrote. It took her just two hours to write her greatest story, "The Lottery."

"The very nicest thing about being a writer is that you can afford to indulge yourself endlessly with oddness, and nobody can really do anything about it, so long as you keep writing and kind of using it up, as it were. All you have to do -- and watch this carefully, please -- is keep writing. So long as you write it away regularly nothing can really hurt you."

For Shirley Jackson, her words spoken at a writers' conference were literally true. As long as she was writing, using up the oddness, as she put it, she remained mentally and emotionally strong. It was between books when she seemed to have her most serious problems.

"Writing itself is a happy act."

Writing can be lonely, difficult, exhausting work, yet as Jackson summarized near the end of her life, it is also happy work. I am rarely happier than when I am writing, or for a few hours after writing something, almost anything, I feel good about. For some of us anyway, writing is good therapy.

Many original, creative people have had the experience of being unpopular in high school.

This is true, of course, not just of budding writers but of teenagers gifted at just about anything other than football and basketball. Partly this may be due to the fact that creative people often tend to be introverts, who are rarely popular, in high school or elsewhere, whatever their natural talents. I am reminded of something Travis Hugh Culley wrote in his memoir A Comedy & A Tragedy. He attended a high school for students gifted in music, art and performance, and he recalls "a thin line ... between being original and being 'a problem.'" Thus creative teens may have difficulty fitting in even when they are surrounded by other creative teens.

Baking a cake was creative, too, after a fashion. You took the ingredients, combined them, and ended up with a product. Not so different from clothespin dolls or short stories, after all.

That reminded me of a blog post I wrote comparing writing with cooking, the blending of ingredients to create something new. A cherry pie is more than just cherries, just flour, just sugar, etc., Blended together and baked, it becomes a new creation. One baker's pie will be different from another baker's pie. In the same way writing involves blending ingredients from different sources, baked in the writer's mind with that writer's own experiences, creating something entirely original.

Throughout her life, Shirley loved the writing of a much earlier age -- Jane Austen, Samuel Richardson, Fanny Burney. These writers "give no sense of being hurried or pressed for unique ideas; they are peaceful and gracious and write with an infinite sense of leisure that I envy greatly," she wrote once.

If you are reading a thriller, "an infinite sense of leisure" is probably not what you want in a writer. "Get on with it," you want to shout whenever there is a break in the action. Yet many of our best writers, including Shirley Jackson, write with an unhurried, easy grace that hides how much work may have gone into each sentence. Or in Jackson's case, her style disguises how quickly she wrote. It took her just two hours to write her greatest story, "The Lottery."

"The very nicest thing about being a writer is that you can afford to indulge yourself endlessly with oddness, and nobody can really do anything about it, so long as you keep writing and kind of using it up, as it were. All you have to do -- and watch this carefully, please -- is keep writing. So long as you write it away regularly nothing can really hurt you."

For Shirley Jackson, her words spoken at a writers' conference were literally true. As long as she was writing, using up the oddness, as she put it, she remained mentally and emotionally strong. It was between books when she seemed to have her most serious problems.

"Writing itself is a happy act."

Writing can be lonely, difficult, exhausting work, yet as Jackson summarized near the end of her life, it is also happy work. I am rarely happier than when I am writing, or for a few hours after writing something, almost anything, I feel good about. For some of us anyway, writing is good therapy.

Friday, October 16, 2015

Shirley Jackson's demons

"To her, wicked and stupid were the same."

Shirley Jackson herself said the recurring theme in her stories, which include the classic short story "The Lottery" and the classic horror novel The Haunting of Hill House, was "an insistence on the uncontrolled, unobserved wickedness of human behavior." Jackson's stories were also very personal. They were about her town of North Bennington, Vt., about her family and about the dual nature of her own personality. She was, as Judy Oppenheimer portrays her in the excellent 1988 biography Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson, both stupid and wicked and both keenly intelligent and an admirable human being, devoted wife, good mother and great American writer.

The demons of Oppenheimer's title refer primarily to the wounds to her psyche left by a disapproving mother who thought her daughter should focus on, to her, important things like popularity and good looks rather than unimportant things like writing stories. She even told her daughter that she was born after an unsuccessful abortion attempt. Jackson tried to be a much better mother to her four children, yet following her premature death at the age of 48, she left most of them with deep psychological wounds that excessive alcohol and drugs failed to cure.

Jackson herself, and here is where she was stupid, ate too much, drank too much and took too many drugs for too long. Those drugs, mostly tranquilizers, were prescribed by her doctor and were thought harmless at the time, but after years of daily use, especially in combination with large quantities of alcohol, they helped bring her to a point where she was afraid to leave her own home. She was happiest when she was writing, but her mistreatment of her body left her unable to write for a long period near the end of her life.

She married her college sweetheart, Stanley Hyman, who later became an influential literary critic. Two odd people, they were ideal for each other. Although he was not a faithful husband and Jackson was constantly jealous of his interest in more attractive women, she never doubted his love for her. She may have been fat and phobic, but Hyman was devoted to her, and her early death left him helpless. He, too, died young, not long after she did.

For a time their home was a gathering place for some of the most important writers of their time, including Ralph Ellison, J.D. Salinger, Peter DeVries and Dylan Thomas. Shirley Jackson could be fun to be around, or she could be a terror if she didn't like you or feared you, as she did most of the residents of her own community, those whose stupidity and wickedness she wrote about in her books.

Said of Shirley Jackson by her daughter Joanne,

quoted in Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson by Judy Oppenheimer

The demons of Oppenheimer's title refer primarily to the wounds to her psyche left by a disapproving mother who thought her daughter should focus on, to her, important things like popularity and good looks rather than unimportant things like writing stories. She even told her daughter that she was born after an unsuccessful abortion attempt. Jackson tried to be a much better mother to her four children, yet following her premature death at the age of 48, she left most of them with deep psychological wounds that excessive alcohol and drugs failed to cure.

Jackson herself, and here is where she was stupid, ate too much, drank too much and took too many drugs for too long. Those drugs, mostly tranquilizers, were prescribed by her doctor and were thought harmless at the time, but after years of daily use, especially in combination with large quantities of alcohol, they helped bring her to a point where she was afraid to leave her own home. She was happiest when she was writing, but her mistreatment of her body left her unable to write for a long period near the end of her life.

She married her college sweetheart, Stanley Hyman, who later became an influential literary critic. Two odd people, they were ideal for each other. Although he was not a faithful husband and Jackson was constantly jealous of his interest in more attractive women, she never doubted his love for her. She may have been fat and phobic, but Hyman was devoted to her, and her early death left him helpless. He, too, died young, not long after she did.

For a time their home was a gathering place for some of the most important writers of their time, including Ralph Ellison, J.D. Salinger, Peter DeVries and Dylan Thomas. Shirley Jackson could be fun to be around, or she could be a terror if she didn't like you or feared you, as she did most of the residents of her own community, those whose stupidity and wickedness she wrote about in her books.

Wednesday, October 14, 2015

Mama and papa

I don't like a kid who calls his mother Mother all the time. It's one of the few prejudices that I got. I think there's something unnatural about it. Maybe it's okay for some kid in England to keep on calling his mother Mother but I don't think it's right over here. A kid should call his mother Ma or Mom. I don't mean Mommy. But not Mother all the time. There's something sneaky about it.

As prejudices go, this one expressed by Jimmy Flannery, Robert Campbell's narrator in The Cat's Meow, seems a bit silly, although don't most prejudices look silly when viewed from a distance? Even so, I'll bet many, perhaps most, of us, react negatively when we hear a child call his mother Mother, or an adult call his mother Mommy. The former seems, if not sneaky as Flannery suggests, at least snobbish. The latter seems childish. At some point in childhood, most of us stopped saying Mommy and Daddy and chose other words to call our parents. I chose Mom and Dad. My son called me Pa, and still does.

We have a number of options in English. For our mother, in addition in those words already mentioned, we can select from maw, mamma, mammy, mam, mater, mum, mumsy, mummy, mummy and even motherkins. Other choices for fathers include papa, pater, pappy and pop. For grandparents the options seem to be endless. Often it comes down to however a child first pronounces grandpa or grandma.

And that brings me to Vivian Cook's discussion in It's All in a Word. Cook wonders why in most of the world's languages, the words for father begin with a p or a t and the words for mother start with an m. He suggests three possibilities. One is that when you are a baby looking at your parents' faces, the "only sounds you can 'see' them make are with the lips and the tongue near the front of the mouth." That means words beginning with p, t or m.

Another theory is that "the easiest way for babies to make a consonant is to open and close the lips, getting a 'p' or 'b' sound, or keep the lips closed and divert the air to the nose to get an 'm.'"

Yet another possibility is that the similar words came simply from babies' babbling. Babies, he says, have been heard to say mama as early as two weeks after birth. As far as their mothers are concerned, their little darlings have said their first word.

I find it fascinating that the dearest words in the English language, or any language, may have come literally from the mouths of babes.

Robert Campbell, The Cat's Meow

As prejudices go, this one expressed by Jimmy Flannery, Robert Campbell's narrator in The Cat's Meow, seems a bit silly, although don't most prejudices look silly when viewed from a distance? Even so, I'll bet many, perhaps most, of us, react negatively when we hear a child call his mother Mother, or an adult call his mother Mommy. The former seems, if not sneaky as Flannery suggests, at least snobbish. The latter seems childish. At some point in childhood, most of us stopped saying Mommy and Daddy and chose other words to call our parents. I chose Mom and Dad. My son called me Pa, and still does.

We have a number of options in English. For our mother, in addition in those words already mentioned, we can select from maw, mamma, mammy, mam, mater, mum, mumsy, mummy, mummy and even motherkins. Other choices for fathers include papa, pater, pappy and pop. For grandparents the options seem to be endless. Often it comes down to however a child first pronounces grandpa or grandma.

And that brings me to Vivian Cook's discussion in It's All in a Word. Cook wonders why in most of the world's languages, the words for father begin with a p or a t and the words for mother start with an m. He suggests three possibilities. One is that when you are a baby looking at your parents' faces, the "only sounds you can 'see' them make are with the lips and the tongue near the front of the mouth." That means words beginning with p, t or m.

Another theory is that "the easiest way for babies to make a consonant is to open and close the lips, getting a 'p' or 'b' sound, or keep the lips closed and divert the air to the nose to get an 'm.'"

Yet another possibility is that the similar words came simply from babies' babbling. Babies, he says, have been heard to say mama as early as two weeks after birth. As far as their mothers are concerned, their little darlings have said their first word.

I find it fascinating that the dearest words in the English language, or any language, may have come literally from the mouths of babes.

Monday, October 12, 2015

A mystery that's the cat's meow

I hadn't read a Jimmy Flannery mystery for many years until I picked up The Cat's Meow recently. Now I remember what I have been missing. Campbell, who died in 2000, wrote 11 Flannery mysteries during the 1980s and 1990s. Each of them has an animal in the title -- Hip-Deep in Alligators, Thinning the Turkey Herd, Sauce for the Goose and so forth. Flannery is a precinct captain in Chicago with a knack for solving problems, including crimes.

In The Cat's Meow, Flannery is asked to see if he can find a way to save a church cemetery that has been sold to make way for a gas station, all the bodies to be moved elsewhere. Soon he becomes involved in the problems of an elderly priest who says he still hears the meow of his dead cat. What's more, there is evidence of devil worship.in the church late at night. When the priest is found dead of an apparent accident, Flannery gets serious about finding out what is really going on in this church.

Campbell tells an interesting story, but the best part is the way he tells it, through the voice of Jimmy Flannery. Flannery's just a nice guy (if not always honest), happily married, eager to help anyone in need and someone with a gift for reading the signs in what others say and do. His grammar isn't always on target, but his insights usually are.

There are hard-boiled mysteries, and then there is the soft-boiled variety. The Cat's Meow is among the best of the latter.

In The Cat's Meow, Flannery is asked to see if he can find a way to save a church cemetery that has been sold to make way for a gas station, all the bodies to be moved elsewhere. Soon he becomes involved in the problems of an elderly priest who says he still hears the meow of his dead cat. What's more, there is evidence of devil worship.in the church late at night. When the priest is found dead of an apparent accident, Flannery gets serious about finding out what is really going on in this church.

Campbell tells an interesting story, but the best part is the way he tells it, through the voice of Jimmy Flannery. Flannery's just a nice guy (if not always honest), happily married, eager to help anyone in need and someone with a gift for reading the signs in what others say and do. His grammar isn't always on target, but his insights usually are.

There are hard-boiled mysteries, and then there is the soft-boiled variety. The Cat's Meow is among the best of the latter.

Friday, October 9, 2015

Why read and write?

Travis Hugh Culley's memoir about his struggle with literacy, A Comedy & A Tragedy, includes a number of good lines about literacy in general. Here are some of them:

Mom believed there was always a name for a thing -- you only had to know where to look. In her mind, the world had already been figured out and that's why we had books. She didn't expect me to take an interest in reading them.

That reminds me of something one of my high school English teachers said. He said the most important thing we would learn in school was not all that information we were struggling to memorize for tests but rather how to find out what we needed to know. We needed to be aware of the kinds of information available in books and then be able to dig out that information as needed. That seems similar to the message conveyed by Culley's mother, except that while he interpreted it to mean literacy wasn't really necessary, I viewed it in a more positive way. Maybe I couldn't learn everything, but if I knew how to read well and how to use a library, I could learn anything.

"And it doesn't matter if you can't write. It doesn't matter if you can or can't read a book! In fact, most people don't read books." He laughed. "If you want to be a part of a big group, don't read anything at all."

Culley's high school friend has put his finger on why so many people can't read or, if they can read, don't read. Their friends don't study, so they don't study. Their friends spend every moment of free time watching television or playing electronic games, so that is what they do. The most literate people may be those with the most literate friends or those capable of leading independent lives. In his book, Culley describes how he made his greatest progress after he moved away from home while still in high school, lived alone and spent long hours in solitude reading and writing.

What I've learned is that literacy is a reflection of a need to document experience.

People write books, journals, e-mails, texts, scholarly papers, whatever, to express what they think, how they feel, what they've done, what they have imagined and so forth. We read to share that experience with others. You can, of course, express the same things by talking, assuming you have someone to talk to, but unless you are recording what you say, you leave no permanent record. To write is not to achieve immortality. Still it is a step in that direction.

By writing, we learn about ourselves.

I had no idea what I was going to say about these lines from Culley's book when I started this post. I just knew they were worth a comment. By putting thoughts into words I learned something about literacy, but mostly I learned something about myself.

Mom believed there was always a name for a thing -- you only had to know where to look. In her mind, the world had already been figured out and that's why we had books. She didn't expect me to take an interest in reading them.

That reminds me of something one of my high school English teachers said. He said the most important thing we would learn in school was not all that information we were struggling to memorize for tests but rather how to find out what we needed to know. We needed to be aware of the kinds of information available in books and then be able to dig out that information as needed. That seems similar to the message conveyed by Culley's mother, except that while he interpreted it to mean literacy wasn't really necessary, I viewed it in a more positive way. Maybe I couldn't learn everything, but if I knew how to read well and how to use a library, I could learn anything.

"And it doesn't matter if you can't write. It doesn't matter if you can or can't read a book! In fact, most people don't read books." He laughed. "If you want to be a part of a big group, don't read anything at all."

Culley's high school friend has put his finger on why so many people can't read or, if they can read, don't read. Their friends don't study, so they don't study. Their friends spend every moment of free time watching television or playing electronic games, so that is what they do. The most literate people may be those with the most literate friends or those capable of leading independent lives. In his book, Culley describes how he made his greatest progress after he moved away from home while still in high school, lived alone and spent long hours in solitude reading and writing.

What I've learned is that literacy is a reflection of a need to document experience.

People write books, journals, e-mails, texts, scholarly papers, whatever, to express what they think, how they feel, what they've done, what they have imagined and so forth. We read to share that experience with others. You can, of course, express the same things by talking, assuming you have someone to talk to, but unless you are recording what you say, you leave no permanent record. To write is not to achieve immortality. Still it is a step in that direction.

By writing, we learn about ourselves.

I had no idea what I was going to say about these lines from Culley's book when I started this post. I just knew they were worth a comment. By putting thoughts into words I learned something about literacy, but mostly I learned something about myself.

Wednesday, October 7, 2015

The right incentive

In his memoir about his struggle learning to read, A Comedy & a Tragedy, Travis Hugh Culley tells how the breakthrough came when he became interested in acting in school productions. That meant memorizing lines in plays, which meant being able to read those lines. That gave him the incentive he needed. Before that, literacy just didn't seem important enough for him to make the effort.

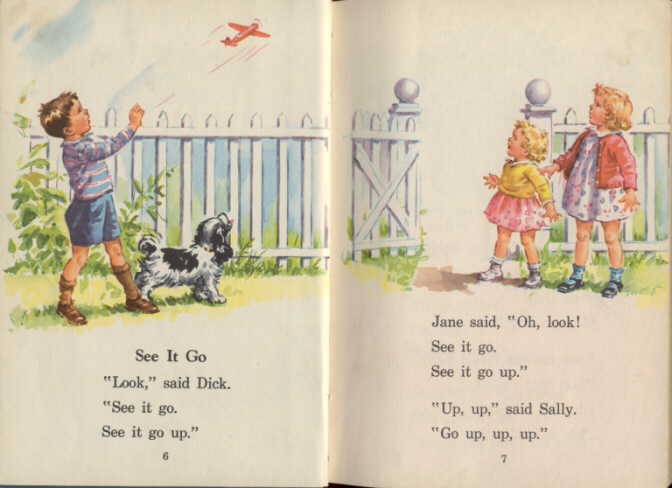

I can recall a time in the third grade when my teacher asked me to tutor Mickey, a boy in the class who was far behind his classmates. I sat with Mickey at his desk, which was one of those with a top that opened up. When Mickey opened his desk, I saw it was filled with automotive magazines. Cars apparently were already his passion, but apparently he just looked at the pictures in those magazines because he struggled to read even the simplest Dick and Jane reader. Even as a third-grader I wondered if Mickey would have more success learning to read if those magazines were used as teaching aids.

Wouldn't the words in those magazines have been too difficult for a beginning reader? Maybe not. In her book It's All in a Word, Vivian Cook writes that by the time children begin learning to read, they are already using multi-syllable words in their speech. So including such words in their readers should not be unreasonable, providing the children are reading something that's interesting to them.

"The important thing is getting the child to see that reading and writing are communicating things like speech," Cook writes. "The words have to relate to interesting things to read about, not to sterile reading book sentences such as Look Spot and See Jane Run."

I learned to read using those Dick and Jane books, and I can still recall how bored I was by them. How much better it would have been to read about cowboys or dinosaurs.

Al Feldstein, former editor of Mad magazine, touched on this subject in an interview he did for the July 2000 edition of The Comics Journal. He said, "Well, I know that kids learn to read well with Mad. I used to get letters from English teachers, that they were using it in remedial reading classes, and in their own regular classes, because it was an easy way to get kids interested in learning syntax and construction. I think we did pretty good in that regard. In terms of writing fairly well."

It's a bit like Field of Dreams and that "if you build it, he will come" line. If you give children something they actually want to read, they will read.

Monday, October 5, 2015

Calvin and Culley

I happened to read Tavis Hugh Culley's book A Comedy & a Tragedy: A Memoir of Learning How to Read and Write at the same time I was reading Bill Watterson's Calvin and Hobbes collection Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons. Sometimes it seemed they were one and the same book.

What these two books, one a memoir and the other a collection of comic strips, have in common, other than their long titles, is that they are both about a boy who defiantly refuses to learn anything in school, even to the point of developing a detailed fantasy life to insulate himself from anything his teacher might be trying to teach.

Here's what Calvin says to his teacher in one panel: "Sorry! I'm here against my will. I refuse to cooperate. They can transport my body to school, but they can't chain my spirit! My spirit roams free! Walls can't confine it! Authority has no power over it!"

"Calvin," replies his teacher, "if you'd put half the energy of your protests into your school work ..."

The boy goes on, "You can try to leave a message, but my spirit screens its calls."

And here is a passage from Culley's book: "In the coming weeks, I found that I could say I did not know the answer to a question, even when I did. I didn't want my teacher to sense what I had become aware of. I didn't want her to know what was on my mind. I wouldn't think. Why think? Instead, I stepped aside and imagined other possibilities. I refused any attempt at reading or writing -- and my rejection was final and radical ..."

Of course, Culley did eventually learn to read and write. He wrote this book, after all. Unlike the comic-strip Calvin, Culley had a dysfunctional family, including a bullying older brother and a mother who pushed drugs on him and kicked him out of the house while he was still in high school. There's so much tragedy in A Comedy & a Tragedy that it's a little hard to see the comedy. Yet there is a happy ending. A bright boy, he essentially taught himself to read, and by keeping a detailed daily journal, to write, and write well.

What these two books, one a memoir and the other a collection of comic strips, have in common, other than their long titles, is that they are both about a boy who defiantly refuses to learn anything in school, even to the point of developing a detailed fantasy life to insulate himself from anything his teacher might be trying to teach.

Here's what Calvin says to his teacher in one panel: "Sorry! I'm here against my will. I refuse to cooperate. They can transport my body to school, but they can't chain my spirit! My spirit roams free! Walls can't confine it! Authority has no power over it!"

"Calvin," replies his teacher, "if you'd put half the energy of your protests into your school work ..."

The boy goes on, "You can try to leave a message, but my spirit screens its calls."

And here is a passage from Culley's book: "In the coming weeks, I found that I could say I did not know the answer to a question, even when I did. I didn't want my teacher to sense what I had become aware of. I didn't want her to know what was on my mind. I wouldn't think. Why think? Instead, I stepped aside and imagined other possibilities. I refused any attempt at reading or writing -- and my rejection was final and radical ..."

Of course, Culley did eventually learn to read and write. He wrote this book, after all. Unlike the comic-strip Calvin, Culley had a dysfunctional family, including a bullying older brother and a mother who pushed drugs on him and kicked him out of the house while he was still in high school. There's so much tragedy in A Comedy & a Tragedy that it's a little hard to see the comedy. Yet there is a happy ending. A bright boy, he essentially taught himself to read, and by keeping a detailed daily journal, to write, and write well.

Friday, October 2, 2015

Can people change?

Fiction teaches you that people change. History, experience, and poetry all teach you this is a lie.

I tend to sit up a little straighter whenever a writer of fiction inserts some broad statement or generalization into a story. Often these aside comments are very good, and I sometimes take note of them, but they can leave me wondering. Whose opinions are they? The story's narrator? A character's? Or the author's? And are they, in fact, true?

Here are a handful I have come across over the years:

"It's like marriage. The race there is between total knowledge of each other and death. If death comes first, it's considered a successful marriage." - Peter S. Beagle, A Fine and Private Place

"Feelings so powerful they could have come only from God lead some to those acts most strongly condemned by His word. It is useless to tell others that the commandments are simple only for those who fail to see why they had to be set down." - Judith Rossner, Emmeline

"There are certain modes of unhappiness with far more style than happiness." - Joyce Carol Oates, Marya: A Life

"It's odd ... how sharing a sense of doubt can bring men together perhaps even more than sharing a faith. The believer will fight another believer over a shade of difference; the doubter fights only with himself." - Graham Greene, Monsignor Quixote

"All men are moral. Only their neighbors are not." - John Steinbeck, The Winter of Our Discontent

And so we come to those lines by Mark Winegardner in his short story "The Visiting Poet." The story is about a poet who teaches at one college after another, on each campus starting affairs with his most beautiful students. Will he, the story asks, ever change and become a man worthy of the love of any woman, including his own daughter? The point the author makes in his aside is that in fiction, people do change. Stories, in fact, are about change. If characters didn't change, stories wouldn't be very interesting. But do people change in real life?

My movie discussion group tackled this very question two weeks ago tonight. The movie was Groundhog Day, that now classic film about a shallow TV weatherman, Phil Connors, who relives the same day hundreds, probably thousands of times, until he finally gets it right, acting not out of self-interest but because he sincerely loves and respects every person he meets. The fact that it takes Phil three days just to avoid stepping into the pothole filled with icy water shows he is a slow learner, but eventually he does become a better person. But is he really changed, we wondered, or may he eventually go back to being the kind of man he was on that first Groundhog Day?

Yet whatever Winegardner or his narrator thinks, people do seem to change in real life. Often this is simply because of maturity or advancing age. There is usually a point in the criminal justice system where repeat offenders become just mostly harmless old people. Youthful playboys sometimes become faithful spouses. From what we know of the Apostle Paul and former Watergate villain Charles Colson, religious conversion can also change people.

Even so, for many of us to change dramatically, it would take more than a few thousand Groundhog Days.

Mark Winegardner, "The Visiting Poet," That's True of Everybody

Here are a handful I have come across over the years:

"It's like marriage. The race there is between total knowledge of each other and death. If death comes first, it's considered a successful marriage." - Peter S. Beagle, A Fine and Private Place

"Feelings so powerful they could have come only from God lead some to those acts most strongly condemned by His word. It is useless to tell others that the commandments are simple only for those who fail to see why they had to be set down." - Judith Rossner, Emmeline

"There are certain modes of unhappiness with far more style than happiness." - Joyce Carol Oates, Marya: A Life

"It's odd ... how sharing a sense of doubt can bring men together perhaps even more than sharing a faith. The believer will fight another believer over a shade of difference; the doubter fights only with himself." - Graham Greene, Monsignor Quixote

"All men are moral. Only their neighbors are not." - John Steinbeck, The Winter of Our Discontent

And so we come to those lines by Mark Winegardner in his short story "The Visiting Poet." The story is about a poet who teaches at one college after another, on each campus starting affairs with his most beautiful students. Will he, the story asks, ever change and become a man worthy of the love of any woman, including his own daughter? The point the author makes in his aside is that in fiction, people do change. Stories, in fact, are about change. If characters didn't change, stories wouldn't be very interesting. But do people change in real life?

My movie discussion group tackled this very question two weeks ago tonight. The movie was Groundhog Day, that now classic film about a shallow TV weatherman, Phil Connors, who relives the same day hundreds, probably thousands of times, until he finally gets it right, acting not out of self-interest but because he sincerely loves and respects every person he meets. The fact that it takes Phil three days just to avoid stepping into the pothole filled with icy water shows he is a slow learner, but eventually he does become a better person. But is he really changed, we wondered, or may he eventually go back to being the kind of man he was on that first Groundhog Day?

Yet whatever Winegardner or his narrator thinks, people do seem to change in real life. Often this is simply because of maturity or advancing age. There is usually a point in the criminal justice system where repeat offenders become just mostly harmless old people. Youthful playboys sometimes become faithful spouses. From what we know of the Apostle Paul and former Watergate villain Charles Colson, religious conversion can also change people.

Even so, for many of us to change dramatically, it would take more than a few thousand Groundhog Days.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)