The international bestseller Love in Lowercase by Spanish novelist Francesc Miralles is an intriguing, off-the-wall love story that, depending upon one's point of view, could also be seen as either full of philosophical wisdom or a collection of trite sayings.

Samuel is an introverted college literature professor who sees a woman he believes to be Gabriela, a girl he met briefly as a young boy and has never forgotten. He thinks she's the love of his life. She thinks he's nuts. While he tries to find her again and then build a relationship with her, other changes come to his life. There is the stray cat that shows up at his door and doesn't want to leave (except when a pretty vet comes to give him a shot). There's an old writer who lives upstairs and, when he goes into a hospital, asks Samuel to help him finish the book he is writing. And there is a strange man named Valdemar, who may be insane or may perhaps the sanest one of them all.

Ever so often, Love in Lowercase gives readers a line worth reading, underlining or perhaps laughing at. Among them:

"Words shape thoughts."

"Science is a shortcut to God."

"The opposite is best. Whenever you're angry with someone, apply this maxim. It means doing the exact opposite of what your body's telling you to do."

"Remember that nothing happens without a reason."

"Never reject your sensations and feelings. They're all you've got."

"Experience can never be shared. It's served in separate packets."

Perhaps the best of these is summarized in the title. This is when "some small act of kindness sets off a chain of events that comes around again in the form of multiplied love."

The gist of the novel, or at least what I like best, is the idea of taking life as it happens and following it where it leads. Plans are fine, but they rarely work out anyway. Better to practice love in lower case, then see what happens.

Friday, March 31, 2017

Wednesday, March 29, 2017

All about the girl

There are trends in book titles as in most things. There was a time long ago when a book's title could take up an entire page. Some old books might have two titles, separated by the word or. Much more recently, one-word titles became popular. We had Jaws, Coma, Topaz and the like.

A recent visit to a bookstore alerted me to the fact that the current trend is for novels to have the word girl in the title, possibly replacing the trend of novels with the word daughter in the title. About a decade ago I wrote a newspaper column that listed scores of daughter novels, and it was an incomplete list.

The girl trend started slowly several years ago with books like Girl with a Pearl Earring and then the popular series that included The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played with Fire, The Girl in the Spider Web and The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest. Then came the bestsellers Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train, and the trend was in full swing.

Now one can find The Girl Before, Luckiest Girl Alive, Copygirl, Hemingway's Girl, The House Girl, The Silent Girls, The Perfect Girl, Girl in Translation, Pretty Girls, Sad Girls, Lilac Girls, The Girl Who Came Home, The Painted Girls, The Girl in the Glass, The Girl in the Castle, Vinegar Girl, The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane, Small Town Girl, The Girls, The Forgotten Girls, The Girl You Left Behind, The Girl From the Train, The Girls in the Garden, The Girl in the Glass, Silver Girl, All the Summer Girls, All the Pretty Girls and The Wicked Girls.

These girls come from all over the world: The Danish Girl, The German Girl, The English Girl, Vegas Girls, The Girl From Kilkenny, Shanghai Girls, The Girl From Venice, The Girl from Krakow and An Irish Country Girl.

Many of these girls seem to be in peril: Girl Waits with Gun, Girl in Pieces, Girl on Ice and The Burning Girl.

I found just one such book among the teen titles: Weregirl. So most of these novels were written for adults, and most of them were written by women for women, and most of the title characters presumably are women, never mind the girls in the titles. And never mind all the scolding men have endured for referring to anyone over 18 as a girl.

Even more than the word daughter, the word girl in a title, suggests youth. Readers, like moviegoers, seem to prefer stories about young women. Old women can find themselves in perilous situations, but you rarely find novels or movies about them. A novel called The Old Lady on the Train or The Forgotten Middle-Aged Women probably wouldn't sell very well.

A recent visit to a bookstore alerted me to the fact that the current trend is for novels to have the word girl in the title, possibly replacing the trend of novels with the word daughter in the title. About a decade ago I wrote a newspaper column that listed scores of daughter novels, and it was an incomplete list.

The girl trend started slowly several years ago with books like Girl with a Pearl Earring and then the popular series that included The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played with Fire, The Girl in the Spider Web and The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest. Then came the bestsellers Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train, and the trend was in full swing.

Now one can find The Girl Before, Luckiest Girl Alive, Copygirl, Hemingway's Girl, The House Girl, The Silent Girls, The Perfect Girl, Girl in Translation, Pretty Girls, Sad Girls, Lilac Girls, The Girl Who Came Home, The Painted Girls, The Girl in the Glass, The Girl in the Castle, Vinegar Girl, The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane, Small Town Girl, The Girls, The Forgotten Girls, The Girl You Left Behind, The Girl From the Train, The Girls in the Garden, The Girl in the Glass, Silver Girl, All the Summer Girls, All the Pretty Girls and The Wicked Girls.

These girls come from all over the world: The Danish Girl, The German Girl, The English Girl, Vegas Girls, The Girl From Kilkenny, Shanghai Girls, The Girl From Venice, The Girl from Krakow and An Irish Country Girl.

Many of these girls seem to be in peril: Girl Waits with Gun, Girl in Pieces, Girl on Ice and The Burning Girl.

I found just one such book among the teen titles: Weregirl. So most of these novels were written for adults, and most of them were written by women for women, and most of the title characters presumably are women, never mind the girls in the titles. And never mind all the scolding men have endured for referring to anyone over 18 as a girl.

Even more than the word daughter, the word girl in a title, suggests youth. Readers, like moviegoers, seem to prefer stories about young women. Old women can find themselves in perilous situations, but you rarely find novels or movies about them. A novel called The Old Lady on the Train or The Forgotten Middle-Aged Women probably wouldn't sell very well.

Monday, March 27, 2017

Not quite over the hill

As a younger man, my idea of a great spy novel was Robert Littell's The Amateur (1981) or James Grady's Six Days of the Condor (1974), tales about young men, inexperienced in the ways of espionage agents, who get the best of veterans. Now, an "old boy" myself, I am nuts about Old Boys (2004), written by Charles McCarry when he was about the same age I am now. His novel is about veteran CIA agents who should be retired but instead team up to find an old friend (and his mother) and prevent a nuclear terrorist attack on U.S. cities.

So maybe my taste in espionage thrillers is a reflection of my stage of life, why I would rather watch movies starring Robert Redford, Tom Hanks, Morgan Freeman or Harrison Ford than ones starring any younger actor you might name. Or maybe all three are terrific novels. When I reread Six Days of the Condor recently, I enjoyed it just as much as I did back in the Seventies.

McCarry has been writing Paul Christopher novels since the Seventies (and I loved The Tears of Autumn and The Secret Lovers, too). In Old Boys, Christopher is in his seventies when he learns that his mother, who disappeared during World War II, may still be alive. And so he disappears, too. When ashes purported to be his are sent back from China, his old friends don't believe it. Horace Hubbard, Christopher's cousin, takes the lead, and he and the other geezers travel back and forth across the globe tracking down the Christophers, while at the same time preventing an even older terrorist from getting his dying wish, the destruction of America.

The novel includes a reference to The Over the Hill Gang. This story is similar to that old movie, but without the laughs. These Old Boys manage to stay a step ahead of much younger men, who keep trying to discourage them and send them back to retirement homes. Of these younger agents, McCarry writes, "Little did they know that they had just been extricated from the mess they had gotten themselves into by a bunch of arthritic, pill-taking old men who last saw combat before these kids' fathers were born."

As an arthritic, pill-taking old man, I found that great fun.

So maybe my taste in espionage thrillers is a reflection of my stage of life, why I would rather watch movies starring Robert Redford, Tom Hanks, Morgan Freeman or Harrison Ford than ones starring any younger actor you might name. Or maybe all three are terrific novels. When I reread Six Days of the Condor recently, I enjoyed it just as much as I did back in the Seventies.

McCarry has been writing Paul Christopher novels since the Seventies (and I loved The Tears of Autumn and The Secret Lovers, too). In Old Boys, Christopher is in his seventies when he learns that his mother, who disappeared during World War II, may still be alive. And so he disappears, too. When ashes purported to be his are sent back from China, his old friends don't believe it. Horace Hubbard, Christopher's cousin, takes the lead, and he and the other geezers travel back and forth across the globe tracking down the Christophers, while at the same time preventing an even older terrorist from getting his dying wish, the destruction of America.

The novel includes a reference to The Over the Hill Gang. This story is similar to that old movie, but without the laughs. These Old Boys manage to stay a step ahead of much younger men, who keep trying to discourage them and send them back to retirement homes. Of these younger agents, McCarry writes, "Little did they know that they had just been extricated from the mess they had gotten themselves into by a bunch of arthritic, pill-taking old men who last saw combat before these kids' fathers were born."

As an arthritic, pill-taking old man, I found that great fun.

Friday, March 24, 2017

A celebration of printing

New technologies always give rise to new cultural anxieties.

Once we have found the secret to the letters, there will be no need for scribes.

Most of us have, several times in our own lifetimes, seen how new technologies have produced radical cultural change and, therefore, new cultural anxieties. Consider the impact of the computer and the cell phone. Those even older remember how television and air conditioning altered their lives. What we don't often think about is how, even several centuries ago, the same phenomenon took place: Technology brought change and, with it, anxiety.

We know before we open Alix Christie's 2014 novel Gutenberg's Apprentice how it will turn out: Johann Gutenberg is going to print a Bible using movable type. Before 1450, Bibles and every other kind of book had to be copied by hand by scribes, a long process that meant every book was precious but also that there were very few books and little reason for most people to learn how to read. So whatever tension and drama the novel contains has to do with how the printing press will change the known world. How will the church accept it? How will the aristocracy accept it? Will his press make Gutenberg rich or put him in prison?

Christie sticks close to the facts, adding details, conversations and minor characters. Her focus is not on Gutenberg but Peter Schoeffer, a young man trained as a scribe and ready to begin a career copying sacred books. Then his foster father, Johann Fust, convinces him to become Gutenberg's apprentice. Fust has invested money in Gutenberg's idea for a printing press, and he wants Peter both to keep an eye on his investment and get in on the ground floor of what could be an important new technology. It is he who tells Peter, "Once we have found the secret to the letters, there will be no need for scribes."

So while Gutenberg is the driving force of the project and Fust bankrolls it, Peter eventually becomes committed to the idea and contributes many of the innovations that make it successful (even though Gutenberg later claims he did it all by himself). Meanwhile there is the constant threat of interference from church leaders, as well as Peter's on-again, off-again romance with a young woman who isn't so sure God wants his Bible to be reproduced by machine.

Christie had never written a novel before, but she is a professional printer, which gives her a unique appreciation for what Gutenberg and Schoeffer went through. And her novel, published by Harper, may not be Gutenberg's Bible, but it nevertheless is a wonderful piece of printing in itself. Few novels are as physically beautiful as this one.

Andrew Root, Christianity Today (March 2017)

Alix Christie, Gutenberg's Apprentice

Christie sticks close to the facts, adding details, conversations and minor characters. Her focus is not on Gutenberg but Peter Schoeffer, a young man trained as a scribe and ready to begin a career copying sacred books. Then his foster father, Johann Fust, convinces him to become Gutenberg's apprentice. Fust has invested money in Gutenberg's idea for a printing press, and he wants Peter both to keep an eye on his investment and get in on the ground floor of what could be an important new technology. It is he who tells Peter, "Once we have found the secret to the letters, there will be no need for scribes."

So while Gutenberg is the driving force of the project and Fust bankrolls it, Peter eventually becomes committed to the idea and contributes many of the innovations that make it successful (even though Gutenberg later claims he did it all by himself). Meanwhile there is the constant threat of interference from church leaders, as well as Peter's on-again, off-again romance with a young woman who isn't so sure God wants his Bible to be reproduced by machine.

Christie had never written a novel before, but she is a professional printer, which gives her a unique appreciation for what Gutenberg and Schoeffer went through. And her novel, published by Harper, may not be Gutenberg's Bible, but it nevertheless is a wonderful piece of printing in itself. Few novels are as physically beautiful as this one.

Wednesday, March 22, 2017

Great literature on postage stamps

When I attend a stamp show, which isn't often, I seek out stamps with literary themes, those devoted to certain authors or certain literary works. This is what I did last weekend when I visited a stamp show in Largo, Fla.

When I attend a stamp show, which isn't often, I seek out stamps with literary themes, those devoted to certain authors or certain literary works. This is what I did last weekend when I visited a stamp show in Largo, Fla. In 1992, the death of Alfred, Lord Tennyson (in 1892) was remembered with the issue of four gorgeous stamps honoring the great poet and his work. Each stamp shows an image of Tennyson at a different stage of his life, as well as paintings by the likes of John Waterhouse and Dante Gabriel Rossetti tied to certain Tennyson poems.

In 1992, the death of Alfred, Lord Tennyson (in 1892) was remembered with the issue of four gorgeous stamps honoring the great poet and his work. Each stamp shows an image of Tennyson at a different stage of his life, as well as paintings by the likes of John Waterhouse and Dante Gabriel Rossetti tied to certain Tennyson poems. Great Britain commemorated the Year of the Child in 1979 with four stamps showing characters from notable children's books by British authors. These include Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter and The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame.

Great Britain commemorated the Year of the Child in 1979 with four stamps showing characters from notable children's books by British authors. These include Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter and The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame.I paid just five bucks for all of these beauties. Each will make a very fine addition to my album.

Monday, March 20, 2017

Bookstore art

There are books about books, but there are also books about bookshops. The latter has practically become its own genre in both fiction (The Little Paris Bookshop, Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore, The Bookshop on the Corner, The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry) and nonfiction (My Bookstore, The Yellow-Lighted Bookshop, Overheard at the Bookstore, The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap).

Add to that second list Bob Eckstein's Footnotes* from the World's Greatest Bookstore, published last year. Surprisingly, this is first an art book. Eckstein did watercolor paintings of the fronts of scores of great bookstores from around the world, most of them still open but some of them no longer in business. He also tells us a little something about each store, then includes quotations about the store from owners, staff members and customers.

Eckstein is a New Yorker, so a significant number of the stores are in and around New York City, but some are as far away as India, Germany, Japan, Great Britain and Paris. The Librairie Avant-Garde in Nanjing, China, is located in the tunnel of a former bomb shelter. The Moravian Book Shop in Bethlehem, Penn., is the oldest continuously operating bookshop in the world. Quimby's in Chicago specializes in graphic novels. The Weapon of Mass Instruction in Argentina is a military tank converted into a roving bookstore. A daughter confessed to spreading her late father's ashes in various places in City Lights Booksellers in San Francisco because it had been one of his favorite places in the world.

I am pleased to have shopped in some of the stores Eckstein paints and writes about. These include Parnassus Books in Nashville, Powell's Books in Portland and John K. King Used & Rare Books in Detroit. Most of the others are still on my bucket list.

Friday, March 17, 2017

Collectible typewriters

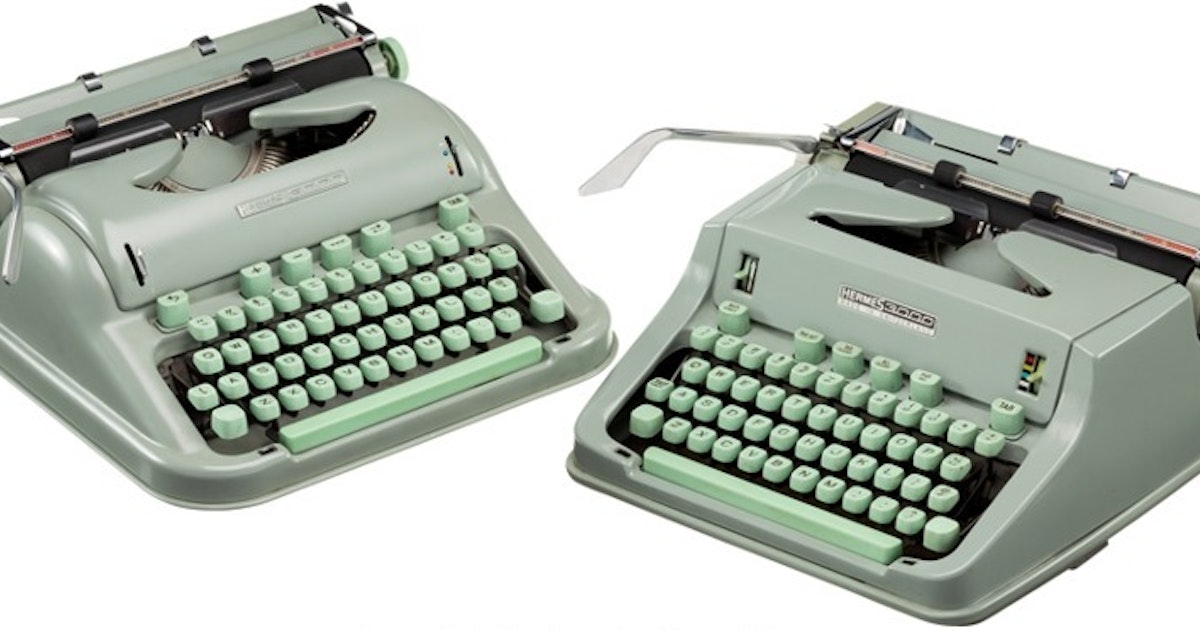

Last week somebody from Texas paid $37,500 for two typewriters. What made these typewriters worth that kind of money? That they belonged to author Larry McMurtry is only half of the answer. The other half is that these are the typewriters McMurtry used to write his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Lonesome Dove (1985).

In those days McMurtry divided his time between his home in Archer, Texas, and his used book business in Washington, D.C. He kept a Hermes 3000 typewriter at each location so he could work on his novel, and presumably other books and screenplays, at either location.

The writer commented that since he owns 15 typewriters, he no longer needed these two and decided to sell them through a New York auction house. The opening bid was set at $10,000, and the winning bidder chose to remain anonymous. That the bidding went as high as it did suggests others were interested in the typewriters, as well, for their literary importance and perhaps for their importance to Texas history.

The sale of McMurtry's typewriters reminds us that literary collectibles include more than just first editions of important books. Almost anything owned or signed by a great writer can be valuable to a collector. One of my own prized possessions is a letter I received from novelist Michael Shaara asking for my permission to use a quotation from my review of The Killer Angels as a blurb on the paperback. That line was carried on paperback editions for many years. A book dealer told me that when I am ready to sell my first edition of that novel, the letter will enhance its value.

The homes of many writers, including the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Thomas Wolfe, are now open to the public. These are the best places for objects once owned by writers, and we can hope that the typewriters once owned by Larry McMurtry, now 80, will eventually find their way back to Archer, Texas, and back to the home of this notable Texas writer.

In those days McMurtry divided his time between his home in Archer, Texas, and his used book business in Washington, D.C. He kept a Hermes 3000 typewriter at each location so he could work on his novel, and presumably other books and screenplays, at either location.

The writer commented that since he owns 15 typewriters, he no longer needed these two and decided to sell them through a New York auction house. The opening bid was set at $10,000, and the winning bidder chose to remain anonymous. That the bidding went as high as it did suggests others were interested in the typewriters, as well, for their literary importance and perhaps for their importance to Texas history.

The sale of McMurtry's typewriters reminds us that literary collectibles include more than just first editions of important books. Almost anything owned or signed by a great writer can be valuable to a collector. One of my own prized possessions is a letter I received from novelist Michael Shaara asking for my permission to use a quotation from my review of The Killer Angels as a blurb on the paperback. That line was carried on paperback editions for many years. A book dealer told me that when I am ready to sell my first edition of that novel, the letter will enhance its value.

The homes of many writers, including the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Thomas Wolfe, are now open to the public. These are the best places for objects once owned by writers, and we can hope that the typewriters once owned by Larry McMurtry, now 80, will eventually find their way back to Archer, Texas, and back to the home of this notable Texas writer.

Wednesday, March 15, 2017

A painted bird

The Jewish boy saved himself from the Nazis in Poland by pretending to be a Catholic, even to the point of becoming an altar boy. Pretending to be someone else became a way of life for Jerzy Kosinski (he was born Jozef Lowenkopf), the noted Polish-American author and the protagonist of Jerome Charyn's new novel, Jerzy. "I cannot function without disguises and masks," Charyn has Kosinski say.

The theme of pretense and disguise fills Charyn's novel, and it isn't only the title character who is a master of deception. The novel begins, in fact, with actor Peter Sellers, gifted at impersonation, who played the lead role in the film Being There, adapted from one of Kosinski's novels. Other people whose lives intersected with Kosinski's, including Princess Margaret and Svetlana Alliluyeva (Stalin's daughter), were good at playing roles. Of one character we are told, "Gabriela would undergo sudden changes. She'd show up dressed as a man, her long hair pulled back and hidden under a hat." Jerzy remembers his father playing chess with himself: "He could change his persona, according to which side of the board he was on."

"We're all painted birds," Jerzy says at one point, a reference to another of his novels, The Painted Bird. Charyn seems to suggest that everyone is something of a fake, our real selves hidden behind paint or false smiles or other people's hats.

The novel wanders, going back and forth in time with a variety of different narrators picking up the thread of the story. We read, in no particular order, about his survival during World War II, his escape to the West, his coming to the United States in 1957, his marriage to an alcoholic heiress, his literary success and then the accusation that he plagiarized much of his work. It was quite a life, in reality as well as in fiction, before it ended prematurely with suicide in 1991. Unfortunately it was the real Jerzy Kosinski who died that day.

The theme of pretense and disguise fills Charyn's novel, and it isn't only the title character who is a master of deception. The novel begins, in fact, with actor Peter Sellers, gifted at impersonation, who played the lead role in the film Being There, adapted from one of Kosinski's novels. Other people whose lives intersected with Kosinski's, including Princess Margaret and Svetlana Alliluyeva (Stalin's daughter), were good at playing roles. Of one character we are told, "Gabriela would undergo sudden changes. She'd show up dressed as a man, her long hair pulled back and hidden under a hat." Jerzy remembers his father playing chess with himself: "He could change his persona, according to which side of the board he was on."

"We're all painted birds," Jerzy says at one point, a reference to another of his novels, The Painted Bird. Charyn seems to suggest that everyone is something of a fake, our real selves hidden behind paint or false smiles or other people's hats.

The novel wanders, going back and forth in time with a variety of different narrators picking up the thread of the story. We read, in no particular order, about his survival during World War II, his escape to the West, his coming to the United States in 1957, his marriage to an alcoholic heiress, his literary success and then the accusation that he plagiarized much of his work. It was quite a life, in reality as well as in fiction, before it ended prematurely with suicide in 1991. Unfortunately it was the real Jerzy Kosinski who died that day.

Monday, March 13, 2017

A secret life

Joyce Carol Oates mentions quite a number of great writers in the course of her short suspense novel Jack of Spades, yet one she doesn't mention, Robert Louis Stevenson, may be the most influential, for her novel reads like a repackaged version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Andrew J. Rush is a successful, middle-aged mystery novelist who, late at night, churns out violent, cheap thrillers under the name of Jack of Spades. Even his dear wife and grown children do not know he is the author of such trash. Gradually we see the mild Andrew J. Rush transform into the wild Jack of Spades. At first he only hears his voice, as if an evil imp were whispering into his ear. Then he launches into a secret life, usually late at night, when he does things Rush would have never considered. In time his entire personality changes, he drinks more and, as Andrew J. Rush, he finds he can write nothing, but as Jack of Spades he becomes prolific.

Stephen King isn't exactly a character in the novel, yet he is mentioned often enough to be one. Rush regards King as his only serious rival. Then it turns out that a frustrated writer who sues Rush, accusing him of breaking into her home and stealing her story ideas, has also sued King, accusing him of the same thing. When Jack of Spades does, in fact, break into the woman's house he finds that the plots of her stories have an uncanny resemblance to those of both Rush and King.

Another major influence on the story is the work of Edgar Allan Poe. At times Oakes makes her tale as eerie as anything Poe produced. There's even a spooky black cat, if not a raven.

Andrew J. Rush is a successful, middle-aged mystery novelist who, late at night, churns out violent, cheap thrillers under the name of Jack of Spades. Even his dear wife and grown children do not know he is the author of such trash. Gradually we see the mild Andrew J. Rush transform into the wild Jack of Spades. At first he only hears his voice, as if an evil imp were whispering into his ear. Then he launches into a secret life, usually late at night, when he does things Rush would have never considered. In time his entire personality changes, he drinks more and, as Andrew J. Rush, he finds he can write nothing, but as Jack of Spades he becomes prolific.

Stephen King isn't exactly a character in the novel, yet he is mentioned often enough to be one. Rush regards King as his only serious rival. Then it turns out that a frustrated writer who sues Rush, accusing him of breaking into her home and stealing her story ideas, has also sued King, accusing him of the same thing. When Jack of Spades does, in fact, break into the woman's house he finds that the plots of her stories have an uncanny resemblance to those of both Rush and King.

Another major influence on the story is the work of Edgar Allan Poe. At times Oakes makes her tale as eerie as anything Poe produced. There's even a spooky black cat, if not a raven.

Friday, March 10, 2017

A creative partnership

| Ruta Sepetys |

Readers, she said, "tell you what your book is about." Her novels, including Salt to the Sea, have been translated into a variety of languages, and when she goes on a book tour, it takes her to several different countries. Wherever she goes, she said, readers see her books differently. What they are about in one place, is not what they are about somewhere else.

Each reader, in fact, no matter where he or she may live, reads something different in a book. "The reader is always right," Sepetys said.

I have always been a bit skeptical about the phrase, "The customer is always right." When I am the customer, I know I am not always right. I doubt that other customers are always right either. Readers are another matter, however. When you read a book, your opinion is the only one that matters. What you think it is about is what it is about. The author's opinion is just the author's opinion, no better than yours. The same is true of book critics and reviewers, whose opinions may be worth reading, but that doesn't make them anything other than their own opinions.

Writers, she said, are in a "creative partnership" with readers. As in any good partnership, both partners need the other. Writers need someone to read their books. Readers need someone to write them. Beyond that, however, is the creative part of that partnership in which writers and readers together determine the value and meaning of a book.

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

Reading movies

Thomas C. Foster is the University of Michigan English professor responsible for such books as How to Read Literature Like a Professor and How to Read Novels Like a Professor. His latest book, Reading the Silver Screen, takes a similar approach, but with films rather than novels as his subject. It doesn't work as well this time, but he does make some interesting points, most notably the one contained in his title: By giving attention to detail, we can "read" movies in much the same way we read novels.

Most people just watch movies for entertainment. They enjoy the story, or not, then forget about it. Even when it is a film they love to watch again over and over, like Gone With the Wind or The Princess Bride, they still watch it for entertainment, nothing more. Foster's point is that even an entertaining film like The Bourne Identity or Blazing Saddles will reward us if we watch it more than once and pay close attention to the details. How is the plot constructed? What role does the music play? How much does the story depend on words and how much on what we see?

"I would argue that reading movies proves to be the harder task since they roll relentlessly forward, twenty-four frames to the second, with no pauses for reflection," Foster writes. "If you stop to analyze what just happened, you miss what's happening now." With a novel, you can stop at anytime to reflect, or you can reread what you just read as many times as you want.

As an occasional leader of film discussions, I find I watch a movie once just for its entertainment value. If I find myself thinking about questions raised by the film, I watch it a second time to determine how suitable it would be for a group discussion. Then I will watch it again for a third or fourth time with pen in hand, taking notes about anything in the movie that might be worth talking about. If a DVD has a director's commentary, I will listen to that, too, for insights into the movie.

As an occasional leader of film discussions, I find I watch a movie once just for its entertainment value. If I find myself thinking about questions raised by the film, I watch it a second time to determine how suitable it would be for a group discussion. Then I will watch it again for a third or fourth time with pen in hand, taking notes about anything in the movie that might be worth talking about. If a DVD has a director's commentary, I will listen to that, too, for insights into the movie.

Foster discusses a great many films, both recent ones like Birdman and The King's Speech and older classics like Safety Last! and The Magnificent Seven. His book, published in 2016, is similar in format to David Thomson's How to Watch A Movie (2015), which mentions many of the same films. Foster's book may seem more like a college class, yet Thomson's is more intellectual and will appeal more to those who take movies very seriously. For the rest of us, Foster may have more to offer.

Most people just watch movies for entertainment. They enjoy the story, or not, then forget about it. Even when it is a film they love to watch again over and over, like Gone With the Wind or The Princess Bride, they still watch it for entertainment, nothing more. Foster's point is that even an entertaining film like The Bourne Identity or Blazing Saddles will reward us if we watch it more than once and pay close attention to the details. How is the plot constructed? What role does the music play? How much does the story depend on words and how much on what we see?

"I would argue that reading movies proves to be the harder task since they roll relentlessly forward, twenty-four frames to the second, with no pauses for reflection," Foster writes. "If you stop to analyze what just happened, you miss what's happening now." With a novel, you can stop at anytime to reflect, or you can reread what you just read as many times as you want.

As an occasional leader of film discussions, I find I watch a movie once just for its entertainment value. If I find myself thinking about questions raised by the film, I watch it a second time to determine how suitable it would be for a group discussion. Then I will watch it again for a third or fourth time with pen in hand, taking notes about anything in the movie that might be worth talking about. If a DVD has a director's commentary, I will listen to that, too, for insights into the movie.

As an occasional leader of film discussions, I find I watch a movie once just for its entertainment value. If I find myself thinking about questions raised by the film, I watch it a second time to determine how suitable it would be for a group discussion. Then I will watch it again for a third or fourth time with pen in hand, taking notes about anything in the movie that might be worth talking about. If a DVD has a director's commentary, I will listen to that, too, for insights into the movie.Foster discusses a great many films, both recent ones like Birdman and The King's Speech and older classics like Safety Last! and The Magnificent Seven. His book, published in 2016, is similar in format to David Thomson's How to Watch A Movie (2015), which mentions many of the same films. Foster's book may seem more like a college class, yet Thomson's is more intellectual and will appeal more to those who take movies very seriously. For the rest of us, Foster may have more to offer.

Saturday, March 4, 2017

Interesting detours

When writers of fiction stray from their story, or seem to stray from their story, it can be annoying for readers, who usually just want to find out what happens next. Instead authors stick in a flashback or a long descriptive passage. Or they feed us more technical or historical detail than we really want to know. Or they simply change the focus from one character to another just as things are getting interesting. Even if the interruption makes the story better in the end, as it usually does, we readers can get impatient.

Yet while reading Alexander McCall Smith's 2011 novel Bertie Plays the Blue, I noticed I didn't mind the author's frequent asides at all. In fact, I even found myself looking forward to them. When he strays from the plot in this novel, as in his others, the story actually seems to get better. This may have something to do with the law-key nature of McCall Smith's plots. Or it may just be that when he takes us on a detour, it is usually an interesting detour.

On page 94 of this novel, for example, Stuart is talking with Bertie, his six-year-old son, about girls, whom Bertie is convinced just want to push boys around. Stuart says, "You must remember that there are some very nice girls ... out there." At that point Stuart begins thinking about that phrase "out there." What does it mean? Where is "out there" anyway? Are the girls "out there" really any different than the girls Bertie goes to school with? This meditation goes on for a page, and while we would like to get back to Bertie, everybody's favorite character in the 44 Scotland Street novels, we don't really mind the interruption. At least I didn't.

On page 102 we are treated to a discussion of the movie Casablance between Pat and her father, Dr. Macgregor. This may have nothing to do with the story we are reading, but if you have seen Casablanca (and who hasn't?) you won't mind. And then they go from talking about the movie to talking about why people no longer talk to each other like they do in that movie, using complete sentences. (Even though that is exactly what Pat and her father are doing.) By page 104 the conversation, very much like a real conversation, has shifted again, this time to the topic of rudeness on the web and in traffic. All this has nothing to do with McCall Smith's story, except that this is always how he tells his stories. It may not be the most direct way to get from the beginning of a story to the end, but it certainly is the scenic route.

Yet while reading Alexander McCall Smith's 2011 novel Bertie Plays the Blue, I noticed I didn't mind the author's frequent asides at all. In fact, I even found myself looking forward to them. When he strays from the plot in this novel, as in his others, the story actually seems to get better. This may have something to do with the law-key nature of McCall Smith's plots. Or it may just be that when he takes us on a detour, it is usually an interesting detour.

On page 94 of this novel, for example, Stuart is talking with Bertie, his six-year-old son, about girls, whom Bertie is convinced just want to push boys around. Stuart says, "You must remember that there are some very nice girls ... out there." At that point Stuart begins thinking about that phrase "out there." What does it mean? Where is "out there" anyway? Are the girls "out there" really any different than the girls Bertie goes to school with? This meditation goes on for a page, and while we would like to get back to Bertie, everybody's favorite character in the 44 Scotland Street novels, we don't really mind the interruption. At least I didn't.

On page 102 we are treated to a discussion of the movie Casablance between Pat and her father, Dr. Macgregor. This may have nothing to do with the story we are reading, but if you have seen Casablanca (and who hasn't?) you won't mind. And then they go from talking about the movie to talking about why people no longer talk to each other like they do in that movie, using complete sentences. (Even though that is exactly what Pat and her father are doing.) By page 104 the conversation, very much like a real conversation, has shifted again, this time to the topic of rudeness on the web and in traffic. All this has nothing to do with McCall Smith's story, except that this is always how he tells his stories. It may not be the most direct way to get from the beginning of a story to the end, but it certainly is the scenic route.

Thursday, March 2, 2017

Stranger (and duller) than fiction

Now, my own suspicion is that the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.

Human behavior, being very much a part of the universe, is no less queer than everything else. As predictable as some people seem to be, we never really know what they are going to say or do next. It is why drivers need to be constantly alert, why long-married people can still surprise their mates and why newspapers have no trouble filling their pages each day.

It is also why the old adage "truth is stranger than fiction" is really true. Novelist Joanne Harris phrased that idea differently in an article she wrote for a recent edition of BookPage, a free publication often distributed in libraries and bookstores. "The fact is that real life is nowhere near as plausible as fiction," she wrote, "...and if I were to base my books on actual, real life incidents encountered during my teaching career, the critics would scoff and refuse to believe that any such thing had happened."

Most of us can recall some very odd things that have happened to us over the years, coincidences that might seem far-fetched if we encountered them in a work of fiction. To mention just one small example from my own life, in the eighth grade we boys were split into basketball teams that played during the noon hour. Of course, the first order of business was to choose a name. For some reason, the name Turtles came to my mind. I decided not to propose it, however, because Turtles seemed like a ridiculous name for a basketball team. Yet at that instant another boy said, "Let's call ourselves the Turtles," and everybody thought that was a great idea. There was nothing mystical there or supernatural, but I think even J.B.S. Haldane would have agreed it was queer.

Most writers of fiction strive to make their stories believable, and that, as Harris suggests, may mean making them a little less like real life. This involves more than just eliminating the strangeness of real life. It also means eliminating all those necessary but boring things that fill so much of our days, everything from brushing our teeth and getting dressed in the morning to making beds and preparing meals. Nobody wants to read that kind of detail in a novel, yet that is what real life is like. Even if you think you lead an exciting life, the really interesting things that happen occupy just a small portion of a typical day.

Real life, thus, is both more strange and more dull and routine than any novel. No matter how realistic a novel may seem, it is still fiction.

J.B.S. Haldane, Possible Worlds

| Joanne Harris |

Most of us can recall some very odd things that have happened to us over the years, coincidences that might seem far-fetched if we encountered them in a work of fiction. To mention just one small example from my own life, in the eighth grade we boys were split into basketball teams that played during the noon hour. Of course, the first order of business was to choose a name. For some reason, the name Turtles came to my mind. I decided not to propose it, however, because Turtles seemed like a ridiculous name for a basketball team. Yet at that instant another boy said, "Let's call ourselves the Turtles," and everybody thought that was a great idea. There was nothing mystical there or supernatural, but I think even J.B.S. Haldane would have agreed it was queer.

Most writers of fiction strive to make their stories believable, and that, as Harris suggests, may mean making them a little less like real life. This involves more than just eliminating the strangeness of real life. It also means eliminating all those necessary but boring things that fill so much of our days, everything from brushing our teeth and getting dressed in the morning to making beds and preparing meals. Nobody wants to read that kind of detail in a novel, yet that is what real life is like. Even if you think you lead an exciting life, the really interesting things that happen occupy just a small portion of a typical day.

Real life, thus, is both more strange and more dull and routine than any novel. No matter how realistic a novel may seem, it is still fiction.

Wednesday, March 1, 2017

A life with meaning

Researchers found that when nursing home residents were given a plant for their rooms, those charged with caring for the plants themselves were more social and more healthy than those told nurses would take care of the plants for them. Fewer of these people died during the course of the study. Clearly it doesn't take much to give life meaning, to make sticking around seem worthwhile. Yet so many people, including those younger, healthier and with seemingly more to live for than those nursing home residents, find their lives meaningless.

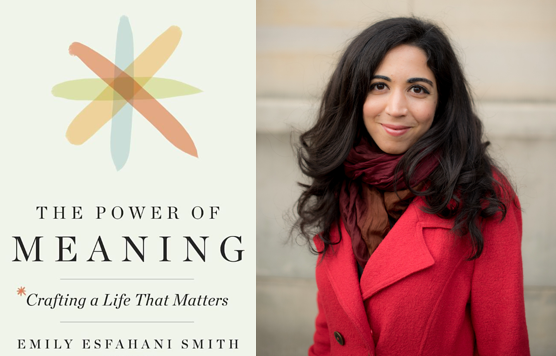

Emily Esfahani Smith explores the vital importance of having a sense of meaning in one's life in her new book The Power of Meaning: Crafting a Life That Matters. She finds four pillars on which this sense of meaning rests.

Belonging: When there's somebody who thinks you matter, you are more likely to feel that you matter. And if you matter to them, they are likely to matter to you.

Purpose: The contribution one makes to the world need not be anything grand. It can be something as small as taking care of a plant.

Storytelling: The simple act of telling the story of your life to others can reveal what your life actually means.

Transcendence: The night sky, a religious experience, a baby's ear, the Grand Canyon -- such things can make us feel small and insignificant, yet at the same time make us feel a part of something grand and eternal.

Smith provides excellent examples of each of these pillars and builds a solid case for the importance of each in our lives. Yet she nearly lost me very early in her book. In her introduction she writes about how after her Iranian family settled in Montreal, their Sufi faith and weekly meetings with other Sufis gave meaning to their lives. But then she casually writes, "My family eventually drifted away from the formal practice of Sufism," as if the faith that supposedly gave their lives meaning was of no more significance than a house plant.

Emily Esfahani Smith explores the vital importance of having a sense of meaning in one's life in her new book The Power of Meaning: Crafting a Life That Matters. She finds four pillars on which this sense of meaning rests.

Belonging: When there's somebody who thinks you matter, you are more likely to feel that you matter. And if you matter to them, they are likely to matter to you.

Purpose: The contribution one makes to the world need not be anything grand. It can be something as small as taking care of a plant.

Storytelling: The simple act of telling the story of your life to others can reveal what your life actually means.

Transcendence: The night sky, a religious experience, a baby's ear, the Grand Canyon -- such things can make us feel small and insignificant, yet at the same time make us feel a part of something grand and eternal.

Smith provides excellent examples of each of these pillars and builds a solid case for the importance of each in our lives. Yet she nearly lost me very early in her book. In her introduction she writes about how after her Iranian family settled in Montreal, their Sufi faith and weekly meetings with other Sufis gave meaning to their lives. But then she casually writes, "My family eventually drifted away from the formal practice of Sufism," as if the faith that supposedly gave their lives meaning was of no more significance than a house plant.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)