Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Getting a pass

Monday, April 28, 2025

Read it again

The process of relearning enriches each day of our life.

Angus Fletcher, Wonderworks

|

| Angus Fletcher |

We forget so much of what we experience, Relearning is the act of bringing it back.

As Fletcher's book, Wonderworks, is about literature, he is particularly interested in what happens when we read books we have read previously. He writes, "As you start to turn the pages, you'll feel your brain entwining old details it remembers with new ones it never grasped before, mingling nostalgia with epiphany and making the novel feel novel once more."

Rereading a novel provides two benefits — becoming reacquainted with characters and a plot we had previously enjoyed and discovering new insights we totally missed the first time through — "mingling nostalgia with epiphany," as Fletcher puts it.

"So, by forgetting and then relearning, we create an opportunity for a special kind of discovery that brings wisdom from the past but also fresh eyes from the present," he says.

Thus, forgetting much or even most of what we've read can actually be a good thing, as strange as that sounds. Relearning leads to deeper learning.

The catch, of course, is that we actually have to read the book a second time.

Friday, April 25, 2025

The science in literature

Fletcher argues that literature can accomplish certain goals, such as feeding creativity, decreasing loneliness and warding off despair. Certain authors and certain books have proved inventive in demonstrating how to accomplish such things with mere words.

The authors he discusses are diverse, from Homer, Plato and Shakespeare to Franz Kafka, Maya Angelou and Tina Fey. The works discussed range from the Book of Job and Hamlet to Winnie-the-Pooh and To Kill a Mockingbird.

At one time, he writes, it was thought that literature, especially popular novels, caused anxiety, especially among women. Virginia Woolf, among others, showed through the invention of stream of consciousness writing that literature could do just the opposite.

How can reading The Godfather improve your health? Fletcher tells us how. What was Jane Austen's contribution to neuroscience? He explains, "Prior to Jane Austen, no novels had drawn us into feeling irony and love at the same time."

This book, while not easy reading, gives us an inventive way to look at literature.

Wednesday, April 23, 2025

The war goes on

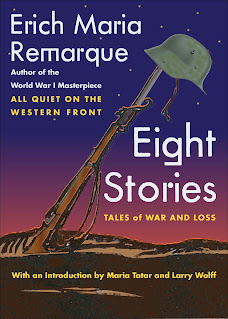

Dehumanizing the enemy comes with the territory during wartime. It can take years for former enemies to seem human again. Following World War I, this process sped along more quickly thanks to Erich Maria Remarque and his great novel All Quiet on the Western Front. Published in 1928, the book describing the war from a German point of view quickly became an international bestseller, even in countries such as the United States that a decade before had been at war with Germany.

Remarque later became a U.S. citizen and married a movie star (Paulette Goddard), but he continued to write about the war from the German point of view. Among these writings is Eight Stories (2018), a collection of tales he wrote for American magazines, mostly Collier's.The stories show us that long after a war is over and after the citizens of warring nations have accepted each other as human again, the war still goes on for those who fought on the front lines. They can never really go home again

In "Where Karl Had Fought," a friend drives Karl Broeger back to the battlefield where he had fought 10 years before. A bank manager now, he was a sergeant then, leading a charge. The narrator says, "In the midst of the fourteen thousand crosses on the broad central pathway a solitary man, remote and small, goes to and fro, ever to and fro. That is more afflicting than if all were still. Karl pushes on."

"Josef's Wife" tells of a soldier who doesn't remember his wife when he is brought home to her after the war. They own a farm, but he is useless on it. Nothing helps Josef until his wife decides to take him back to the battlefield, to the very site where he sustained his injuries.

The first story in the book may be the best of the lot. Called "The Enemy," the story makes the point that the real enemy in wartime is not the soldiers on the other side but rather the weapons that all soldiers carry. When one holds a tool of any kind, whether it's a hammer or a gun, it must eventually be put to use.

In the story, German and French soldiers temporarily put down their weapons and exchange simple gifts in no man's land. This echoes a true story about a brief Christmas truce between the trenches in 1914, dramatized in the wonderful French film Joyeux Noel.

All of these stories are brief. Each is poignant. Together they give us a picture of war that lasts as long as the soldiers do.

Monday, April 21, 2025

Genuine poetry

|

| T.S. Eliot |

I am not sure I understand that, but it does communicate something to me. Poetry is an art, perhaps the oldest literary art. One need not understand a painting, a ballet or a symphony for it communicate something to you, so why not poetry? Perhaps it is simply a feeling or a mood. The point of Magsamen and Ross's book is that art makes us feel better, and so it must communicate something.

I notice that Eliot, himself a genuine poet, used the adjective genuine in his comment. Even that part of the statement makes us wonder what he meant. Did he mean serious poetry? Good poetry? Did he mean poetry that by its very nature can be challenging to understand or that can be understood in a multitude of ways?

The authors observe that poems are often read at celebrations and ceremonial events, such as funerals, weddings, commencements and presidential inaugurations. These read or recited poems are not necessarily understood by everyone who hears them, yet they do communicate something. They declare that this is a serious moment, a profound moment. It is the kind of moment that genuine poets write about.

Friday, April 18, 2025

Ordinary people

Several of them were fishermen. One was a tax collector, even less popular with his countrymen than an IRS agent would be today. One was a zealot, what in today's world we might call an activist, an extremist or even a terrorist. For most of the 12, we have no idea what they were. We know virtually nothing about them, yet MacArthur someone manages to write several pages about each of them.

He writes 35 pages about Peter, who is mentioned again and again in the gospels and in Acts, yet then manages 16 pages about Nathanael, even after beginning by saying he is mentioned just twice in John's gospel and elsewhere named only in the lists of disciples. In other words, MacArthur knows how to make much out of very little.

He calls Nathanael "the guileless one," Philip "the bean counter," Andrew "the apostle of small things" and so on. For each there is a lesson in the author's hands. Together they teach the lesson that Jesus has a purpose for all varieties of ordinary people.

Wednesday, April 16, 2025

The importance of art

"Art-making laid the basic foundation for cultural and community among our earliest ancestors," they say late in their book. Without art, we as a people could not exist. And even if we can exist as individuals without art, we cannot exist very well. A healthy, happy life requires art in some form, they argue.

It helps that the authors expand art in ways you may not have imagined. Gardening or the presentation of food on a plate can be creative outlet. (A woman working at a buffet restaurant once complimented me for how artistic my salad looked.) So can listening to music as well as making music. Or taking a walk in the woods. Even looking out a window at a natural setting can make us feel better. They cite a study showing that hospital patients with beds next to a window tend to have shorter stays.

Art need not be good to be beneficial. They point to a study showing "that the simple act of doodling increases blood flow and triggers feelings of pleasure and reward. It turns out that doodlers are more analytical, retain information better, and are better focused than their non-doodling colleagues."

Music helps those with dementia. Dancing benefits those with Parkinson's disease. Coloring books reduce stress. "The arts have the ability to transform you like nothing else," they write.

Their book, unfortunately, does not make easy reading. Reading it often seems more like work than relaxing art appreciation.

Monday, April 14, 2025

A bit part

Friday, April 11, 2025

Book ownership

|

| Charles Lamb |

Charles Lamb

A book reads the better which is our own ... (I don't know why Charles Lamb put that comma in there. It seems unnecessary to me.)

I have long felt this way. I rarely visit the public library these days because I no longer listen to recorded books, and they were just about the only thing I have borrowed from libraries for many years. Once I could afford to buy my own books I mostly stopped borrowing library books. I am a condo librarian and often donate books to the cause, yet I have rarely borrowed a book from this collection.

For many years I received books for review from publishers, and these became my books. I didn't have to give them back, though I eventually gave most of them away.

I dislike borrowing books from friends.

Like Lamb, I much prefer reading my own books. There is no deadline for finishing them, or even for starting them. Usually books sit on my shelves for years waiting their turn. I seem to know when it comes time to read them.

After I have read them — and as Lamb observes, they are often stained with tea and various food particles if I read them at mealtimes — I put the best of them back on my shelves or, nowadays, in a box in my storage unit. I like looking at them and knowing they are there in case I ever need to refer to them or, in some cases, read them a second or third time.

The best books in the world, as far as I am concerned, are those that belong to me.

Wednesday, April 9, 2025

Around and around the world

"It seems," said the woman, "that the world you travel through is not the same world we travel through."

Douglas Westerbeke, A Short Walk Through a Wide World

Can you imagine a woman who cannot stay in one place for more than three days without becoming seriously ill and so spends her life traveling, mostly on foot, around the world again and again? Well, Douglas Westerbeke can, and the result is his engaging fantasy, A Short Walk Through a Wide World (2024).It is 1895 in Paris when this strange affliction first strikes nine-year-old Aubry Tourvel. Eventually she must abandon her mother and keep walking. She fashions a spear, disguised as a walking stick, with which she learns to kill her own food. She explores different cultures and gets to know countless people, however briefly. Lovers come and go. Friends come and go. Or rather, they come and she goes. She must keep moving to stay alive.

Marta, a journalist who wants to write about Aubry, keeps up with her the longest. She becomes a close friend, but eventually she also must be left behind.

Aubry not only sees the world like no other person, she also experiences a world no other person gets to see. Often she finds shortcuts, such as through the Himalayas, in the form of libraries full of books that consist of drawings, not words. Eventually she adds her own story in pictures.

Fantasies often take us to other worlds. Westerbeke takes us through this world in surprising ways.

Monday, April 7, 2025

After Reichenbach

Sherlock Holmes has been fair game for numerous mystery writers over the years. Laurie R. King, for example, has written a popular series of novels featuring Holmes as an old man. What's different about Anthony Horowitz is that he has the sanction of the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle estate to write his books.

One of these is Moriarty (2015), an exciting tale about what happens after that incident at Reichenbach Falls, where both Holmes and Moriarty are presumed to have died in their struggle. Inspector Athelney Jones of Scotland Yard (mentioned in the Holmes stories) meets Frederick Chase of the Pinkertons over a body, presumed to be Moriarty's, Chase is in pursuit of an American master criminal, Clarence Devereux, believed to have migrated to England to take over Moriarty's criminal empire. And Devereux is much more violent than Sherlock's foe ever was.Jones, who has studied to make himself Holmes-like in his detective skills, teams with Chase in pursuit of Devereaux. They trace him to the American embassy in London, where because of diplomatic immunity he seems untouchable.

The struggle to stop Devereaux takes violent and unexpected turns, with the final surprise likely to shock most readers. Holmes himself does not appear in this inventive novel, but Holmes fans will not want to miss it anyway.

Friday, April 4, 2025

A writer or not?

If you talk, you are a talker. If you golf, you are a golfer. If you write, you are a writer.

Roy Peter Clark, Murder Your Darlings

|

| Roy Peter Clark |

Even when I wrote for a newspaper every day, I did not think of myself as a writer. I was a journalist. I was a newspaperman. I did not call myself a writer.

In retirement I continue to write almost every day. I post something on this blog three days a week. Often I blog about the act of writing. Otherwise I write lots of emails and a few letters. For the past couple of years I have been writing and preaching sermons on occasion. I write, but does that really make me a writer?

The problem, I think, is that the word suggests a certain level of professionalism. A novelist is a writer. Someone whose articles are printed in magazines is a writer. A blogger, on the other hand, is a blogger.

Can a portly middle-aged man who plays softball on weekends justifiably call himself an athlete? Should someone who plays Chopsticks on a piano be able to call himself a pianist? Can a woman who sometimes works on a friend's hair refer to herself as a hairdresser?

How we think of ourselves is one thing. I can easily be a writer in my own mind. The question is, how does one introduce oneself at parties? I would never tell a stranger that I am a writer, for that would give the wrong first impression. I am simply a retired journalist who still likes to write.

Wednesday, April 2, 2025

Like a wolf in the forest

It's rare to see a person with a book or magazine these days; it's like glimpsing a wolf in the forest.

Dwight Garner, The Upstairs Delicatessen

|

| Dwight Garner |

Medical offices and barbershops may still have a few magazines on hand, yet I rarely see anyone looking at them. Instead they are all looking at their phones.

In restaurants, virtually everyone, whether sitting alone or with someone else, is holding a phone in front of them.

I live about a mile from the Gulf of America, but it has been a long time since I have been to the beach, even to see a sunset. Yet I suspect that those reclining in the sun are mostly looking at their phones, not at one of those thick, spicy novels that used to be called "beach books."

I am proud that my granddaughter, like me, packs her books before packing her clothing when taking a trip. She, too, is a rarity in today's world. How many people have books with them on planes, even for long flights? How many take a book with them for a week at a cabin or a resort?

Some people do read e-books, to be sure. I applaud them. Yet somehow it is not quite the same.