Speed and informality have been the strengths of email since its beginning. They have also been its weaknesses.

Letters, whether handwritten or typewritten, take an investment of time to write, and then there is the long wait, usually several days at best, for them to be delivered and for a response to get back to you. With e-mail, the whole process can sometimes be completed in a couple of minutes.

Letters also require a certain formality of structure: a date, a greeting of "Dear So-and So," even when writing to a complete stranger, and a closing of "Sincerely," "Yours truly," "Love" or whatever. Then there is the signature. Should you just sign your first name or your entire name? Email frees you from this formality. You simply say what you have to say. The email system itself usually supplies the date and notifies the recipient of the sender. For busy people, email was a godsend. And then came texting, which is even faster and less formal.

And yet maybe email (not to mention texting and tweeting, right President Trump?) is just too easy. Fast messages can get us in trouble, especially if we are angry and hit the send button before we have had a chance to cool down and think over our message rationally. It is also easy to make mistakes. Meanwhile, the lack of formality can itself be offensive, especially when the recipient is someone who expects a little respect, such as an older person or a powerful person in government or business.

I was interested when, a few weeks ago, Miriam Cross, writing for Kiplinger, urged those wishing to make a good impression to follow some basic etiquette in their more important e-mail. "Save 'Hi' for colleagues and work acquaintances," she wrote. "New clients should be greeted with 'Hello' or "Dear,' followed by 'Mr.' or 'Ms.' (or a professional title) and the person's surname."

"To close the email," Cross wrote, "you can't go wrong with 'Sincerely,' 'Best' or 'Kind regards ..."

In other words, in business, especially at the onset of a new relationship, email should be more like old-fashioned letters, more formal and with a little more time taken to get it right.

Friday, April 28, 2017

Wednesday, April 26, 2017

Smile when you say that, pardner

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said that using exclamation points is like laughing at your own jokes. I like the analogy. In either case, it is telling one's audience how to respond. An exclamation point says, "Hey, pay attention here. This is important!" Laughing at one's own joke says, "Hey, pay attention here. This is funny!" Like Fitzgerald, I favor letting others decide for themselves how they will react. It seems more polite, somehow. Or at least less egotistical.

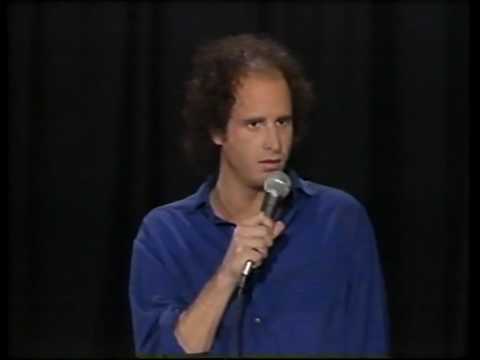

Some comics have laughed at their own jokes and gotten away with it. The laughter of Red Skelton and Phyllis Diller, for example, became a part of their acts. We laughed not just at their jokes but also at their trademark laughter. At the other extreme are those like Steven Wright and Rodney Dangerfield, who would never laugh at their own jokes, or rarely even break a smile. Most successful comedians are more like Wright and Dangerfield than Skelton and Diller.

I know a woman who laughs after virtually everything she says, although I do not recall her ever saying anything funny. Like an exclamation point at the end of every sentence, this creates a boy-who-cried-wolf effect. If she ever does say something funny, how would anyone know?

Come to think of it, I have the same problem. When I attempt wit, I have a straight-faced delivery that Steven Wright might envy. As a consequence, other people, especially those who don't know me very well, can't tell if I'm joking or not. In such situations, their safest response may be none at all. At a party one night I said something that I thought was the wittiest thing anyone said all evening. But I said it with a straight face and a soft voice. Nobody laughed. But my friend, standing next to me, repeated the same line in a loud voice that told everyone he was joking, and he got a huge laugh from everyone there, including those nearby who ignored the quip when I said it.

So what does that tell us? When comics like Steven Wright and Rodney Dangerfield are introduced to an audience, everyone knows they are supposed to be funny, so everyone feels free to laugh. For the rest of us, some compromise may sometimes be necessary. That compromise, like the occasional exclamation point, can simply be a broad smile that warns everyone it's only a joke.

Some comics have laughed at their own jokes and gotten away with it. The laughter of Red Skelton and Phyllis Diller, for example, became a part of their acts. We laughed not just at their jokes but also at their trademark laughter. At the other extreme are those like Steven Wright and Rodney Dangerfield, who would never laugh at their own jokes, or rarely even break a smile. Most successful comedians are more like Wright and Dangerfield than Skelton and Diller.

I know a woman who laughs after virtually everything she says, although I do not recall her ever saying anything funny. Like an exclamation point at the end of every sentence, this creates a boy-who-cried-wolf effect. If she ever does say something funny, how would anyone know?

|

| Steven Wright |

So what does that tell us? When comics like Steven Wright and Rodney Dangerfield are introduced to an audience, everyone knows they are supposed to be funny, so everyone feels free to laugh. For the rest of us, some compromise may sometimes be necessary. That compromise, like the occasional exclamation point, can simply be a broad smile that warns everyone it's only a joke.

Monday, April 24, 2017

Jack lives on

As a consequence, Jack the Ripper has been a character in numerous novels and films, including two books I happened to read recently, Time After Time by Karl Alexander and The Devil's Workshop by Alex Grecian.

I read Time After Time after watching the short-lived ABC series based on the novel that ran in March. The novel was adapted for a movie, also with the same title, starring Malcolm McDowell and Mary Steenburgen a number of years ago.

Alexander's story turns Jack the Ripper into Dr. Leslie John Stephenson, a long-time acquaintance of writer H.G. Wells, who doesn't just write a novel about a time machine but actually builds one, Wells invites some friends over to show them his invention. When Scotland Yard comes knocking at the door looking for Jack the Ripper, Stephenson sees the time machine as a means of escaping for good, as well as providing him with a new killing field.

Stephenson takes the machine to San Francisco in 1979. Wells follows behind him, determined to bring him back to face justice. In the TV series it is a museum employee whom Wells meets, falls in love with and ultimately puts in grave danger. In the novel, she is an employee of the bank where Wells goes to get some 1979 money to finance his chase of Stephenson.

The novel, published in 1979, is much better than the ABC series, which may help explain why the show was canceled so quickly.

The Devil's Workshop, published in 2014, is the third installment of Grecian's excellent Murder Squad series featuring Walter Day and Nevil Hammersmith. It seems that there is a secret group of prominent men, including some present and former police officers, who think prison is too good for criminals like Jack the Ripper. Jack stopped killing only because he had been captured and taken to a torture chamber in the London underground. A prison break is orchestrated, not to set prisoners free but to move them underground where they can be given the punishment they deserve. The plan goes awry, however, and not only do these violent criminals escape, but so does Jack the Ripper.

Things turn very violent before Day and Hammersmith stop the chaos. The action ends at Day's own home, where his dear wife is having their first baby. Yet this doesn't end the story, for one of the men who escapes is another mass murderer called the Harvest Man. Day and Hammersmith must deal with him in the next book in the series, The Harvest Man, now in paperback.

Friday, April 21, 2017

Always room for more books

|

| Jesse Stuart |

Just on the Georgia side of the Georgia-Florida border is a store that sells books returned by public libraries after short-term use. I normally avoid library discards, but these books, although they bear library stamps and plastic covers, are in good condition. Many look like they have hardly been handled at all. Plus the prices are right and the selection is impressive. I can usually find books here I've been looking for but have found nowhere else. This is the third time I've stopped here, and I always find something good.

My catch this time included And After the Fall by Lauren Belfer, At the Edge of the Orchard by Tracy Chevalier, The Painter by Peter Helller, Prayers the Devil Answers by Sharyn McCrumb, First Fix Your Alibi and Blaze Away by Bill James, and The Woman Who Walked in Sunshine by Alexander McCall Smith. These novels had once been part of the Palm Beach County Library, New York Library, Montgomery County, Md., Library, Mid-Manhattan Branch Library and Beaver Creek Library systems.

Taking a different route than usual this year, mainly to avoid Atlanta's traffic congestion, we were surprised to find ourselves in Big Stone Gap, Va., home of the Tales of the Lonesome Pine Bookstore, the subject of The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap, a book I read and enjoyed last year. I had to stop and look around.

Wendy Welch, the author of the book, was away with her husband this week, so I didn't get to talk with her, but I did enjoy browsing through their quaint little used book shop, which also includes an upstairs cafe and, surprisingly, a cat-rescue service. The store has just one cat there now, one that actually lives there, but we were told there are usually several kittens on hand waiting for nice people who come in looking for books and leave carrying kittens.

|

| Mary Mapes Dodge |

I have long wondered what family relationship there might be, if any, between Mary Mapes Dodge, the author of Hans Brinker, and me. Perhaps this book will inspire me to do a little genealogical research.

On the third day of our trip we passed through Greenup County, Ky., home of Jesse Stuart, a favorite writer of mine. Then we stopped in Portsmouth, Ohio, to see the impressive floodwall murals along the Ohio River. Pictured here are many of the notable people from this part of the world, including Roy Rogers, Branch Rickey and, I was happy to see, Jesse Stuart.

Monday, April 17, 2017

Two extremes

For some people, once something is written, it is finished. There is no such thing as a second draft, a revision of an awkward sentence or even a quick read to check spelling and grammar. Science fiction writer Isaac Asimov was famous for this. He wrote as many books as he did, on a variety of subjects other than science fiction, because he could write quickly, but also because he supposedly didn't go back over his work. That's what editors were for.

At the other extreme are those who hesitate to say that anything they write is ever finished. It is for such people that the postscript at the end of letters was invented. Such writers can take years to finish a book, even after they've written the last chapter. They can always find something that can be improved.

I am somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. As a blogger, I tend to quickly forget what I wrote about last week, yet I always have in mind those topics I'm considering for the week ahead. Even so I am often torn by things I have written, especially if I go back and reread them months or years later. There are things I would love to add or take out or simply rewrite in clearer language. And then there are all those typos, so easy to miss when writing is fresh but which seem to jump off the page or the screen months later. Last week, for example, I reread a post from a couple of weeks ago and found I had written two when I meant too. In this case, I actually went back and made the correction. Now it's as if it were correct all along.

This made me wonder if the poet Walt Whitman would have thrived in the digital age, or would the ease of correction driven him to the nuthouse? Whitman's Leaves of Grass was published in 1855, yet he never considered it finished. He was continually thinking of better ways to phrase the lines of his poetry, and each edition of his book published during his lifetime was different than the one before.

But it gets worse. An article in the winter edition of Fine Books & Collections says Whitman stood behind the printer during the first printing of Leaves of Grass and directed changes throughout the printing of the 795 copies in that edition. "As a result, it is possible that each of the 184 known surviving copies is unique," writes Erin Blakemore. A team of scholars is at work comparing original copies of Whitman's work to determine what differences they can find.

All this makes it impossible to know which is the real Leaves of Grass. Which version should be the one reprinted for today's readers, the last one Whitman approved or one of the originals? Who should decide which is best?

At least with Isaac Asimov there will never be that problem.

At the other extreme are those who hesitate to say that anything they write is ever finished. It is for such people that the postscript at the end of letters was invented. Such writers can take years to finish a book, even after they've written the last chapter. They can always find something that can be improved.

I am somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. As a blogger, I tend to quickly forget what I wrote about last week, yet I always have in mind those topics I'm considering for the week ahead. Even so I am often torn by things I have written, especially if I go back and reread them months or years later. There are things I would love to add or take out or simply rewrite in clearer language. And then there are all those typos, so easy to miss when writing is fresh but which seem to jump off the page or the screen months later. Last week, for example, I reread a post from a couple of weeks ago and found I had written two when I meant too. In this case, I actually went back and made the correction. Now it's as if it were correct all along.

| Walt Whitman |

But it gets worse. An article in the winter edition of Fine Books & Collections says Whitman stood behind the printer during the first printing of Leaves of Grass and directed changes throughout the printing of the 795 copies in that edition. "As a result, it is possible that each of the 184 known surviving copies is unique," writes Erin Blakemore. A team of scholars is at work comparing original copies of Whitman's work to determine what differences they can find.

All this makes it impossible to know which is the real Leaves of Grass. Which version should be the one reprinted for today's readers, the last one Whitman approved or one of the originals? Who should decide which is best?

At least with Isaac Asimov there will never be that problem.

Friday, April 14, 2017

Mere Christians

The word fan somehow doesn't seem right for someone who starts reading C.S. Lewis and then somehow never stops. Follower? No. Devotee? Wrong. Admirer? Closer, but still not perfect, since Lewis was never about drawing attention to himself, but rather to Jesus Christ. So how about mere Christian? I like it.

In Mere Christians, edited by Mary Anne Phemister and Andrew Lazo, 55 individuals tell how they got hooked on the writing of C.S. Lewis. The book, published in 2009, could have included thousands more, myself included.

What I found most interesting, for some reason, was the number of entryways into Lewis. Not surprisingly, Mere Christianity is mentioned most often as the book that people read first. Others tell about the influence of the Narnia books. The Screwtape Letters, the science fiction novels and works like Surprised by Joy, The Problem of Pain and Miracles. Yet there are others who cite Lewis's literary works, such as A Preface to "Paradise Lost" and Studies in Words, and essay collections like God in the Dock and The Weight of Glory. Lewis wrote so much and with so much variety, including poetry, with virtually everything still in print, that one can discover him through any one of many doors. And if you read one thing, you tend to seek out others.

I entered through the Mere Christianity door while in college, struck immediately by the strength of his intellect, his logic and his metaphors. Soon I was reading (and collecting) everything by or about Lewis I could get my hands on.

Some of the "mere Christians" included in the book are people you may have heard of, including Charles Colson of Watergate fame, geneticist Francis Collins, pollster George Gallup Jr. and writers like Liz Curtis Higgs, Anne Rice, Philip Yancey, Elton Trueblood and Clyde Kilby. Also included are Joy Davidman, the American poet who became so impressed with Lewis's books that she went to England to meet him and eventually married him, and Merrie Gresham, who married one of Davidman's sons and Lewis's stepsons and only later became a mere Christian herself. It happened because she listened to a tape of Mere Christianity.

In Mere Christians, edited by Mary Anne Phemister and Andrew Lazo, 55 individuals tell how they got hooked on the writing of C.S. Lewis. The book, published in 2009, could have included thousands more, myself included.

What I found most interesting, for some reason, was the number of entryways into Lewis. Not surprisingly, Mere Christianity is mentioned most often as the book that people read first. Others tell about the influence of the Narnia books. The Screwtape Letters, the science fiction novels and works like Surprised by Joy, The Problem of Pain and Miracles. Yet there are others who cite Lewis's literary works, such as A Preface to "Paradise Lost" and Studies in Words, and essay collections like God in the Dock and The Weight of Glory. Lewis wrote so much and with so much variety, including poetry, with virtually everything still in print, that one can discover him through any one of many doors. And if you read one thing, you tend to seek out others.

I entered through the Mere Christianity door while in college, struck immediately by the strength of his intellect, his logic and his metaphors. Soon I was reading (and collecting) everything by or about Lewis I could get my hands on.

Some of the "mere Christians" included in the book are people you may have heard of, including Charles Colson of Watergate fame, geneticist Francis Collins, pollster George Gallup Jr. and writers like Liz Curtis Higgs, Anne Rice, Philip Yancey, Elton Trueblood and Clyde Kilby. Also included are Joy Davidman, the American poet who became so impressed with Lewis's books that she went to England to meet him and eventually married him, and Merrie Gresham, who married one of Davidman's sons and Lewis's stepsons and only later became a mere Christian herself. It happened because she listened to a tape of Mere Christianity.

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

The plague of memory

The more you remember, the more you've lost.

Others ask, is it better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all? Emily St. John Mandel repeatedly asks a slightly different question in her post-apocalyptic novel Station Eleven. Are those who remember the world before civilization ended better or worse off than those who don't?

The question is raised by many different characters in many different ways in the years after the Georgia Flu kills 99.9 percent of the world's population. The only survivors are those who are either immune to the virus or happen to be so isolated that they miss the contagion altogether. So many people are killed that the ability to do everything from produce energy to manufacture virtually anything is lost. People gather into traveling bands, the strong preying on the weak, with everyone constantly searching for food.

As years pass, older people still fondly remember airplanes, computers, cell phones and televisions. Those who are younger remember little or nothing about the civilization that was lost, although a museum established in an abandoned airport gives them some idea. So who is better off? "We long only for the world we were born into," one character says, a commentary most of us can relate to after a certain stage of life, with or without an apocalypse.

Two key characters were small children when civilization ended. The girl, one of the novel's more positive characters, remembers very little of those days. Of the boy, the story's villain, she wonders if he "had had the misfortune of remembering everything."

The story is framed by literature, Shakespeare on one end and a graphic novel called "Station Eleven" on the other. The latter, created by one of the main characters, tells of a space station that has been traveling to distant stars for so many years that the crew has no memory of Earth, the planet where their flight originated. Station Eleven is the world they were born into.

As for William Shakespeare, he was living at the time of the Bubonic Plague, and his work was influenced by it. Station Eleven opens with a production of one of Shakespeare's plays in Toronto just before the Georgia Flu strikes, and afterward one of the roving bands performs his plays on their travels, mostly through what once was Michigan. Computers, cell phones and televisions may no longer be operable, but if Shakespeare survives, can civilization be truly said to have died?

Emily St. John Mandel, Station Eleven

The question is raised by many different characters in many different ways in the years after the Georgia Flu kills 99.9 percent of the world's population. The only survivors are those who are either immune to the virus or happen to be so isolated that they miss the contagion altogether. So many people are killed that the ability to do everything from produce energy to manufacture virtually anything is lost. People gather into traveling bands, the strong preying on the weak, with everyone constantly searching for food.

As years pass, older people still fondly remember airplanes, computers, cell phones and televisions. Those who are younger remember little or nothing about the civilization that was lost, although a museum established in an abandoned airport gives them some idea. So who is better off? "We long only for the world we were born into," one character says, a commentary most of us can relate to after a certain stage of life, with or without an apocalypse.

Two key characters were small children when civilization ended. The girl, one of the novel's more positive characters, remembers very little of those days. Of the boy, the story's villain, she wonders if he "had had the misfortune of remembering everything."

The story is framed by literature, Shakespeare on one end and a graphic novel called "Station Eleven" on the other. The latter, created by one of the main characters, tells of a space station that has been traveling to distant stars for so many years that the crew has no memory of Earth, the planet where their flight originated. Station Eleven is the world they were born into.

As for William Shakespeare, he was living at the time of the Bubonic Plague, and his work was influenced by it. Station Eleven opens with a production of one of Shakespeare's plays in Toronto just before the Georgia Flu strikes, and afterward one of the roving bands performs his plays on their travels, mostly through what once was Michigan. Computers, cell phones and televisions may no longer be operable, but if Shakespeare survives, can civilization be truly said to have died?

Monday, April 10, 2017

Off the beaten path

Atlas Obscura is to places what Ripley's Believe It or Not is to people. It finds points on the map, usually well off the beaten path, whose very existence can amaze us. There's a lake in Mali where fishing is allowed only one day a year, when at a signal men rush in with baskets to scoop up as many fish as they can. A river in Colombia becomes a liquid rainbow for a few weeks every year because of a rare species of river weed. Residents of a village in Poland all decorate their houses with painted flowers.

And so it goes, country by country around the world. A few countries, such as Botswana and Luxembourg, are omitted, but most nations have at least one oddity worth a mention, and most have a number of them. The book compiled by Joshua Foer, Dylan Thuras and Ella Morton is not necessarily a travel guide, for there are several places mentioned you couldn't visit even if you wanted to, whether because they are on private property or because they are in locations where tourism is not allowed, such as Monkey Island in Puerto Rico, where the monkeys carry a herpes virus that can be fatal to humans.

Most of the places mentioned can be visited, and I have seen a few of them myself, including Antelope Canyon in Arizona and Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland, two of the most amazing natural wonders I have ever seen, and such man-made oddities as the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, the Weeki Wachee mermaid show in Florida and Lily Dale, a small town in New York that has long been a hangout for spiritualists.

People everywhere seem to have a fascination with the human body, and the book shows many unusual cemeteries, as well as museums dedicated to torture, mummies, human body parts, undertaking, murders and, tame by comparison, medicine. Quite a number of other attractions are the work of artists, gardeners or people with delusions of grander.

There's an artist in Mexico who built a five-story house for himself in the shape of a nude woman. His bedroom was in one of her breasts. Believe it or not.

And so it goes, country by country around the world. A few countries, such as Botswana and Luxembourg, are omitted, but most nations have at least one oddity worth a mention, and most have a number of them. The book compiled by Joshua Foer, Dylan Thuras and Ella Morton is not necessarily a travel guide, for there are several places mentioned you couldn't visit even if you wanted to, whether because they are on private property or because they are in locations where tourism is not allowed, such as Monkey Island in Puerto Rico, where the monkeys carry a herpes virus that can be fatal to humans.

Most of the places mentioned can be visited, and I have seen a few of them myself, including Antelope Canyon in Arizona and Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland, two of the most amazing natural wonders I have ever seen, and such man-made oddities as the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, the Weeki Wachee mermaid show in Florida and Lily Dale, a small town in New York that has long been a hangout for spiritualists.

People everywhere seem to have a fascination with the human body, and the book shows many unusual cemeteries, as well as museums dedicated to torture, mummies, human body parts, undertaking, murders and, tame by comparison, medicine. Quite a number of other attractions are the work of artists, gardeners or people with delusions of grander.

There's an artist in Mexico who built a five-story house for himself in the shape of a nude woman. His bedroom was in one of her breasts. Believe it or not.

Friday, April 7, 2017

Illogical language

Most of us can think of English words or phrases that, while they might seem to mean the opposite, actually mean the same thing. Take the words flammable and inflammable. How many people have regretted lighting cigarettes in the vicinity of signs warning INFLAMMABLE because they thought the word meant nonflammable?

Or how about the words loose and unloose? Or the phrases "I could care less" and "I couldn't care less?"

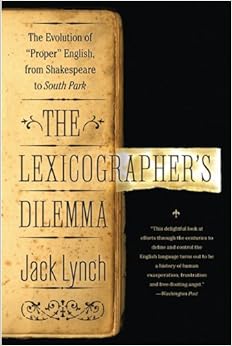

Sometimes the same words can mean opposite things in different contexts. Jack Lynch lists a number of examples in his book The Lexicographer's Dilemma. Take the word oversight. It can mean either watching carefully, as in the case of an oversight committee, or not carefully enough.

To dust something can mean either adding something, as in the case of cookies and powdered sugar, or removing something, as in the case of furniture and actual dust.

Does a bimonthly magazine come out twice a month or every other month? Well, take your pick.

Lynch notes that we might encourage people to eat heartily by telling them to either eat up, chow down, tuck in or pig out. How is it possible that each of these phrases means the same thing?

Those of us who grew up speaking English have no trouble at all with such illogical constructions, with the possible exception of those who light fires around INFLAMMABLE signs. But pity those who try to learn the language as adults.

Or how about the words loose and unloose? Or the phrases "I could care less" and "I couldn't care less?"

Sometimes the same words can mean opposite things in different contexts. Jack Lynch lists a number of examples in his book The Lexicographer's Dilemma. Take the word oversight. It can mean either watching carefully, as in the case of an oversight committee, or not carefully enough.

To dust something can mean either adding something, as in the case of cookies and powdered sugar, or removing something, as in the case of furniture and actual dust.

Does a bimonthly magazine come out twice a month or every other month? Well, take your pick.

Lynch notes that we might encourage people to eat heartily by telling them to either eat up, chow down, tuck in or pig out. How is it possible that each of these phrases means the same thing?

Those of us who grew up speaking English have no trouble at all with such illogical constructions, with the possible exception of those who light fires around INFLAMMABLE signs. But pity those who try to learn the language as adults.

Wednesday, April 5, 2017

The quest for proper English

These two groups, the prescriptivists and the descriptivists, haven't gotten on together very well, and the struggle between them is at the heart of this book.

Those who compile dictionaries are called lexicographers. There are relatively few of them in this world. Does anyone go to college with the idea of becoming a lexicographer? Yet lexicographers serve an important function. The question, as expressed in Jack Lynch's book The Lexicographer's Dilemma, is what exactly is that function? Is it to describe words as they are actually being used in spoken and written language or to determine which uses are, in fact, proper and which are not?

The existence of the American Heritage Dictionary resulted from this conflict, Lynch tells us. Critics decided Webster's Third New International Dictionary in 1961 was just too descriptive, including vulgar words and such words as ain't that, while often heard, had never previously been recognized by a dictionary. So the American Heritage Dictionary was introduced to provide a prescriptive alternative to Webster's.

For most of the history of the English language, there were neither prescriptivists nor descriptivists. But there were no dictionaries either. Those who could write were free to spell words however they wanted to and make them mean whatever they chose. In time, as printed material became more commonplace and more people learned to read and write, some standardization became necessary. This led to dictionaries and, inevitably, to attempts by some people to tell other people the proper way to use their language.

Lynch reviews the contributions to the debate made by such people as John Dryden, Jonathan Swift, Samuel Johnson, Joseph Priestly, Noah Webster, James Murray, George Bernard Shaw and even comedian George Carlin. And it all makes more interesting reading than you might think.

The author concludes by suggesting there is a place for both prescriptivists and descriptivists. What's most important in any language is clarity. I must be able to understand what you are saying, and vice versa. That means we need some common ground about what words mean, how to spell them and how to use them in sentences. Enter parents who correct our grammar and teach us to say please and thank you. Enter teachers who red-ink our theme papers. Enter those copy editors who strive to make sure those books, magazines, newspapers and websites we read are, in fact, readable and understandable.

Instead of worrying about what is correct English, Lynch says, we need to focus on what is appropriate English.

Jack Lynch, The Lexicographer's Dilemma

The existence of the American Heritage Dictionary resulted from this conflict, Lynch tells us. Critics decided Webster's Third New International Dictionary in 1961 was just too descriptive, including vulgar words and such words as ain't that, while often heard, had never previously been recognized by a dictionary. So the American Heritage Dictionary was introduced to provide a prescriptive alternative to Webster's.

For most of the history of the English language, there were neither prescriptivists nor descriptivists. But there were no dictionaries either. Those who could write were free to spell words however they wanted to and make them mean whatever they chose. In time, as printed material became more commonplace and more people learned to read and write, some standardization became necessary. This led to dictionaries and, inevitably, to attempts by some people to tell other people the proper way to use their language.

Lynch reviews the contributions to the debate made by such people as John Dryden, Jonathan Swift, Samuel Johnson, Joseph Priestly, Noah Webster, James Murray, George Bernard Shaw and even comedian George Carlin. And it all makes more interesting reading than you might think.

The author concludes by suggesting there is a place for both prescriptivists and descriptivists. What's most important in any language is clarity. I must be able to understand what you are saying, and vice versa. That means we need some common ground about what words mean, how to spell them and how to use them in sentences. Enter parents who correct our grammar and teach us to say please and thank you. Enter teachers who red-ink our theme papers. Enter those copy editors who strive to make sure those books, magazines, newspapers and websites we read are, in fact, readable and understandable.

Instead of worrying about what is correct English, Lynch says, we need to focus on what is appropriate English.

Tuesday, April 4, 2017

Steinbeck's prophetic novel

The passage of decades has turned John Steinbeck's The Winter of Our Discontent, a contemporary novel about modern trends when it was published in 1961, into a historical novel, a look back at how American life used to be. Yet I am also struck, reading it now all these years later, at what a prophetic novel it was. Steinbeck had his hand on the pulse of the nation. He seemed to know that the discontent he describes in his characters will sweep the country in the 1960s. He wants to blame President Eisenhower for this, but that seems simplistic. More likely it was caused by the period of peace and prosperity, following years of Depression and war, and the hard moral choices required by these sudden good times.

The novel tells of one man's moral choices. Ethan Allen Hawley works as a grocery store clerk, a situation brought about because his father lost the Hawley family fortune. Every day he hears comments about his family's prosperous past and complaints from his wife and children about their relative poverty. It is 1960, and they still do not own a television.

Hawley recalls that as a loyal soldier during the war he had killed enemy soldiers, but he has not killed anyone since then. Killing other men then did not make him an evil man now. Similarly, he reasons, if he can make a small fortune by illegal or immoral means, he can still be a good citizen later when he builds on that fortune and reclaims his place in society. He seriously contemplates robbing the bank next to his store, then finds a way to wealth that will be safer and yet, if anything, more unethical.

Steinbeck structures his plot so that many related elements all happen at once -- an alcoholic friend happens to own the only land in the area suitable for an airport, the owner of the grocery may have entered the United States illegally some 40 years before, town officials are indicted for corruption, Hawley's son enters a national citizenship essay contest and, among other developments, the local banker, whose family may have been responsible for the Hawley family's bankruptcy, is wheeling and dealing to try to build an even larger fortune. That so much happens, even on the same holiday weekend, seems a bit of a stretch, giving The Winter of Our Discontent the feel not so much of a modern novel as of a fable, like so many of Steinbeck's other notable works.

The novel tells of one man's moral choices. Ethan Allen Hawley works as a grocery store clerk, a situation brought about because his father lost the Hawley family fortune. Every day he hears comments about his family's prosperous past and complaints from his wife and children about their relative poverty. It is 1960, and they still do not own a television.

Hawley recalls that as a loyal soldier during the war he had killed enemy soldiers, but he has not killed anyone since then. Killing other men then did not make him an evil man now. Similarly, he reasons, if he can make a small fortune by illegal or immoral means, he can still be a good citizen later when he builds on that fortune and reclaims his place in society. He seriously contemplates robbing the bank next to his store, then finds a way to wealth that will be safer and yet, if anything, more unethical.

Steinbeck structures his plot so that many related elements all happen at once -- an alcoholic friend happens to own the only land in the area suitable for an airport, the owner of the grocery may have entered the United States illegally some 40 years before, town officials are indicted for corruption, Hawley's son enters a national citizenship essay contest and, among other developments, the local banker, whose family may have been responsible for the Hawley family's bankruptcy, is wheeling and dealing to try to build an even larger fortune. That so much happens, even on the same holiday weekend, seems a bit of a stretch, giving The Winter of Our Discontent the feel not so much of a modern novel as of a fable, like so many of Steinbeck's other notable works.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)