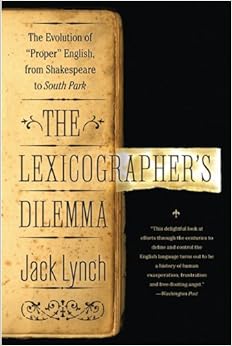

Jack Lynch, The Lexicographer's Dilemma

The existence of the American Heritage Dictionary resulted from this conflict, Lynch tells us. Critics decided Webster's Third New International Dictionary in 1961 was just too descriptive, including vulgar words and such words as ain't that, while often heard, had never previously been recognized by a dictionary. So the American Heritage Dictionary was introduced to provide a prescriptive alternative to Webster's.

For most of the history of the English language, there were neither prescriptivists nor descriptivists. But there were no dictionaries either. Those who could write were free to spell words however they wanted to and make them mean whatever they chose. In time, as printed material became more commonplace and more people learned to read and write, some standardization became necessary. This led to dictionaries and, inevitably, to attempts by some people to tell other people the proper way to use their language.

Lynch reviews the contributions to the debate made by such people as John Dryden, Jonathan Swift, Samuel Johnson, Joseph Priestly, Noah Webster, James Murray, George Bernard Shaw and even comedian George Carlin. And it all makes more interesting reading than you might think.

The author concludes by suggesting there is a place for both prescriptivists and descriptivists. What's most important in any language is clarity. I must be able to understand what you are saying, and vice versa. That means we need some common ground about what words mean, how to spell them and how to use them in sentences. Enter parents who correct our grammar and teach us to say please and thank you. Enter teachers who red-ink our theme papers. Enter those copy editors who strive to make sure those books, magazines, newspapers and websites we read are, in fact, readable and understandable.

Instead of worrying about what is correct English, Lynch says, we need to focus on what is appropriate English.

No comments:

Post a Comment