Whom the gods wish to destroy they first call promising.

Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise

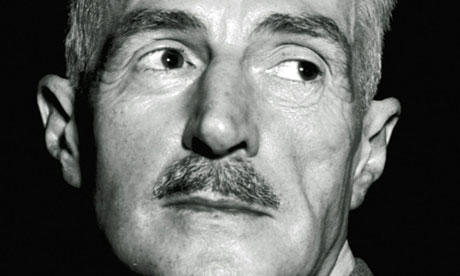

Dashiell Hammett died more than 50 years ago, but one of his short stories,

An Inch and a Half of Glory, appeared in The New Yorker a couple of weeks ago. It reads like a parable.

Earl Parish is one of eight men who race into a burning building after they notice a small boy in an upstairs window. The other seven abandon the rescue when they learn the fire department has arrived, but Earl Parish (Hammett always refers to his main character by his full name) keeps going and soon carries the boy to safety. In the local newspaper's story about the fire the next day, Earl Parish's heroism takes up one and a half inches.

At first Earl Parish is embarrassed by all the attention he receives. Then he comes to enjoy it. Finally, and fatally, he comes to think he deserves it. From that point on, his life spirals downward. He loses his job. He can't hold any other job for long. He considers most jobs beneath him. Even the fire department doesn't want to employ a man who can't stop bragging about his one act of heroism.

Earl Parish has made the mistake, all too common, of believing his own press clippings.

When I was a student at Ohio University, I can remember standing in a long line to see a popular movie at one of the Athens theaters. Then I noticed three members of the school's basketball team walk to the front of the line, buy their tickets and go inside ahead of everyone else who had been standing in that line for a long time. Nobody said a word. It may have had something to do with the fact that these athletes were each a head taller than any of the rest of us, but I think our silence was mainly due to the fact that they were

stars. They had believed their own press clippings and decided the rules that applied to everyone else did not apply to them, and the rest of us let them get away with it. Most of us probably didn't admire them as much afterward, however.

Many athletes seem to fall into the trap of believing what is written about them. Even kids of high school age and younger can easily start believing they are better, somehow more deserving than others their age. The only time I was bullied in high school was by the school's best basketball player, a boy I once cheered when he scored 42 points in a game. The cheers did not make him a better person.

One can only wonder how much of the trouble former New England Patriot Aaron Hernandez is now in, facing murder charges, is due to his believing his own press clippings. Did he come to see himself as being a cut above everyone else? Did he think he could, quite literally, get away with anything?

Are President Obama and members of his administration in so much hot water in Washington these day because they believed a largely supportive press would simply overlook anything they might do?

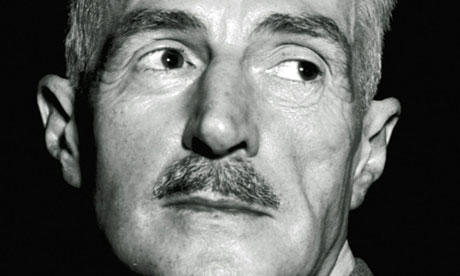

Writers, too, sometimes make the mistake of believing what is said about them. Harper Lee and Truman Capote were childhood friends who went on to become two of America's best 20th century writers. Lee published just one novel, but To Kill a Mockingbird was so highly praised that she became unwilling to risk attempting anything else. Nothing she wrote could ever achieve that standard again, so she wrote nothing. Capote, after the success of In Cold Blood, seemed to like being a celebrity better than being a writer. He let his talent wither away.

There is no telling how many other writers have believed negative reviews and then gave up trying, perhaps much too soon.

Praise is wonderful and criticism may sometimes be necessary, but it can be a mistake to take either too seriously. Rarely are we either as good or as bad as what others say about us.

Do you remember in high school how your teachers told you to write an essay using at least four or six sources, or whatever. Most students in my era just wanted to go to the World Book and paraphrase what they found there. If you followed instructions, however, melding together the information you found in these various sources, you probably came up with the superior essay. It was, at least, original.

Do you remember in high school how your teachers told you to write an essay using at least four or six sources, or whatever. Most students in my era just wanted to go to the World Book and paraphrase what they found there. If you followed instructions, however, melding together the information you found in these various sources, you probably came up with the superior essay. It was, at least, original.