Modern American Literature is a three-volume set of literary reference books once common in many libraries in the United States. The idea was to present excerpts from literary criticism on American writers for the benefit of scholars, mostly high school and college students writing term papers. If you were writing a report on, say, John Dos Passos, you could find a variety of commentary on him and his books all in one place.

When my local library discarded its set of these reference books several years ago, I bought it, and it has been taking up valuable space on my shelf ever since. Lately I have been spending some time with it. When I defended Ogden Nash from criticism of his work by Louis Untermeyer on Oct. 17, I found that criticism in Modern American Literature.

Today I want to dip into these books once again to discuss what some American writers have written about other American writers. I am not so sure writers are the most objective of literary critics. Some view other writers as rivals and so are more likely to be critical of their work. Ernest Hemingway was infamous for this. Others may want to puff up the works of other writers in hopes those writers will return the favor. Read the blurbs on paperback books and you will notice a lot of this going on. So take the following excerpts with caution.

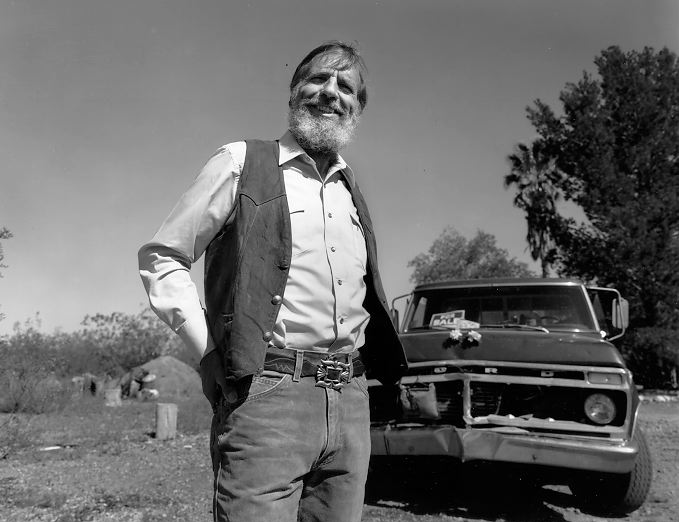

|

| Robert Penn Warren |

Robert Penn Warren on Saul Bellow: "The novel (

The Victim) proved that the author had a masterful control of the method, not merely fictional good manners, the meticulous good breeding which we ordinarily damn by the praise 'intelligent.'"

Archibald MacLeish on Stephen Vincent Benet: "His life was a model, I think, of what a poet's life should be -- a model upon which young men of later generations might well form themselves."

Dawn Powell on James M. Cain: "This is not to say that Mr. Cain's art is not important in its own peculiar way, or that it is mere hammock reading."

Katherine Anne Porter on Willa Cather: "She is a curiously immovable shaped, monumental, virtue itself in her work and a symbol of virtue -- like certain churches, in fact, or exemplary women, revered and neglected."

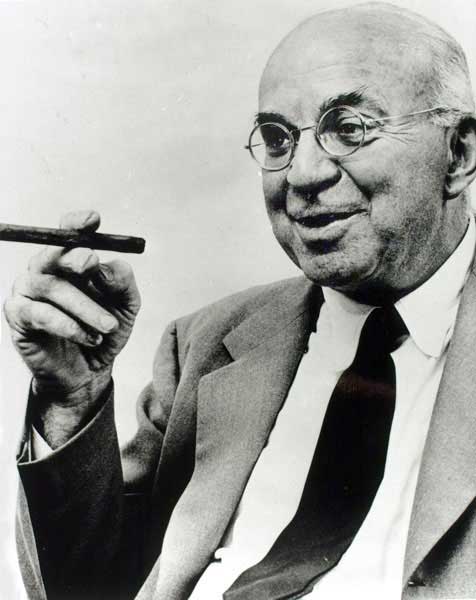

|

| John Dos Passos |

Sinclair Lewis on John Dos Passos: "I regard

Manhattan Transfer as more important in every way than anything by Gertrude Stein or Marcel Proust or even the great white boar, Mr. Joyce's

Ulysses."

Mark Twain on William Dean Howells: "His is a humor which flows softly all around about and over and through the mesh of the page, pervasive, refreshing, health-giving."

Gore Vidal on Carson McCullers: "She was an American legend from the beginning, which is to say that her fame was as much a creation of publicity as of talent."

Ogden Nash on Dorothy Parker: "The trick about her writing is the trick about Ring Larder's writing or Ernest Hemingway's writing. It isn't a trick."

William Carlos Williams on Ezra Pound: "I could never take him as a steady diet. He was often brilliant but an ass."

William Dean Howells on Mark Twain: "An instinct for something chaotic, ironic, empiric in the order of experience seems to have been the inspiration of our humorist's art."

Randall Jarrell on William Carlos Williams: "He is neither wise nor intellectual, but is full of homely shrewdness and common sense, of sharply intelligent comments dancing cheek-to-cheek with prejudice and random eccentricities ..."