Among the many pleasures to be found in Masha Hamilton's The Camel Bookmobile, reviewed here a couple of days ago, are the observations, generalizations and insights various characters have about books. I thought I would collect a few of them here, adding a few comments of my own.

"Books allowed her vicarious tastes of infinite variety, but they didn't supplant the need to venture out into the big and messy. In fact, just the opposite. Books convinced her that something more existed -- something intuitive, beyond reason -- and they whetted her appetite to find it."

It may be easy enough for readers to bury ourselves in our books, to find our romance and adventure there and to learn all about the world we care to know. Or, as with Fi in Hamilton's novel, our reading can send us out into that world, better equipped and more inspired than we might otherwise be.

"The books are like the night for you, aren't they" she said. "You can hide in the stories, and grow there, and come out different."

Ideally that is the case. It may depend, of course, on what it is we are reading.

"I realized right away that books could take us out of ourselves, and make us larger. Even provide us with human connections we wouldn't otherwise have."

Many people, of course, believe just the opposite. How many young introverted readers have been accused of burying themselves in their books when they should be out playing with other children? Yet books can give these same children something to talk about and more confidence to express it when they are around others. They can even help them seek out those who may share their interests and points of view.

"Books, it occurred to her now, were enduring, even immortal."

A good book, anyway, will outlive most of us.

"My girls need the bookmobile. They need the possibilities it brings."

I like that image, that a bookmobile carries not just books, but possibilities.

"As she read, she became fully human again."

I have always found something restorative about reading. At the very least, it can take one's mind off one's troubles, but perhaps any mediocre TV show can do that. Yet while I may sometimes feel guilty after watching a mediocre TV show, I don't feel that way after a mediocre book.

"But the children were all around and Mr. Abasi was calling out and motioning for her to come, and anyway, he knew now, if he hadn't known before, that there were limitations to words -- words in the air or on a page."

Ah, yes, words do have their limitations. Even the best writers must sometimes feel frustrated in their attempts to say all that they feel. How much more difficult it is for the rest of us.

Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Monday, December 29, 2014

Overdue library books

In The Camel Bookmobile (2007), Masha Hamilton weaves a fascinating, multi-layered story about some overdue library books. This isn't an ordinary library, however. The books are, in fact, packed on the back of a camel and taken to remote villages in Kenya, where most of the people can't even read, let alone read English, which is the language most of the donated books happen to be in. The camel bookmobile is viewed differently by different people in these villages. To some it represents progress, the way into the modern world. To others it represents evil, a threat to old ways and old wisdom.

Fiona Sweeney, an idealistic 36-year-old American woman, commits herself to this project, and she particularly enjoys visiting Mididma, an isolated village of semi-nomads which includes a teacher, an old woman and her granddaughter who are literate and treasure books, almost any books Fi happens to bring on the camel.

Among the library patrons is a teenager called Scar Boy since being attacked by a hyena and badly disfigured. When the bookmobile returns to Mididma, Scar Boy refuses to return the books he borrowed, thus threatening the village's future as a stop on the bookmobile's schedule. This is a problem even for those who object to the bookmobile because of the shame it will bring to the village. Everyone begins pressuring Scar Boy to return the books, but it turns out he could no longer return them even if he wanted to.

Much else happens in Hamilton's story. The teacher's lovely wife falls in love with Scar Boy's father, while Fi and the teacher discover a strange attraction to each other. The little girl who loves books decides she wants to follow Fi to America to become a teacher, and Scar Boy is discovered to have a rare talent nobody knew about. Meanwhile a drought threatens the very existence of the village.

The camel bookmobile really exists, and has since 1996. Hamilton's novel, besides telling a delightful story about the power of books, brings our attention to that fact and makes us wonder about some of the true stories it must have inspired.

Fiona Sweeney, an idealistic 36-year-old American woman, commits herself to this project, and she particularly enjoys visiting Mididma, an isolated village of semi-nomads which includes a teacher, an old woman and her granddaughter who are literate and treasure books, almost any books Fi happens to bring on the camel.

Among the library patrons is a teenager called Scar Boy since being attacked by a hyena and badly disfigured. When the bookmobile returns to Mididma, Scar Boy refuses to return the books he borrowed, thus threatening the village's future as a stop on the bookmobile's schedule. This is a problem even for those who object to the bookmobile because of the shame it will bring to the village. Everyone begins pressuring Scar Boy to return the books, but it turns out he could no longer return them even if he wanted to.

Much else happens in Hamilton's story. The teacher's lovely wife falls in love with Scar Boy's father, while Fi and the teacher discover a strange attraction to each other. The little girl who loves books decides she wants to follow Fi to America to become a teacher, and Scar Boy is discovered to have a rare talent nobody knew about. Meanwhile a drought threatens the very existence of the village.

The camel bookmobile really exists, and has since 1996. Hamilton's novel, besides telling a delightful story about the power of books, brings our attention to that fact and makes us wonder about some of the true stories it must have inspired.

Friday, December 26, 2014

Hitchcock's kind of story

I happened to finish reading Past Perfect, the 2007 novel by Susan Isaacs, soon after starting Spellbound by Beauty: Alfred Hitchcock and His Leading Ladies, a 2008 book by Donald Spoto. So naturally I couldn't help thinking about Past Perfect as a Hitchcock movie and Katie Schottland as a Hitchcock heroine.

Spy stories, especially those in which ordinary people (often ordinary women with extraordinary beauty) get caught in dangerous situations) were a Hitchcock staple, from The 39 Steps to Torn Curtain. That's what happens in the Isaacs novel. Actually Katie had worked for the CIA, writing mostly routine reports, in her early 20s, but then 15 years ago she had been fired without explanation. Now she writes a successful television series called Spy Guys, but the unfairness of her termination still rankles. So when she gets a call from Lisa, a former CIA colleague, asking for her help and, as bait, promising to reveal the truth about why she was canned, Katie is hooked. But then Lisa never calls back.

Katie wonders if something might have happened to Lisa, but mostly she just wants to get to the bottom of her disgrace of 15 years before. So, her son off to summer camp and her husband preoccupied with his work, she begins making contact with people she worked with at the agency, including her former boss with whom, like many other women in his department, she had had a brief fling. Though a novice at actual espionage, Katie keeps digging until she uncovers the whole complicated truth, nearly at the cost of her life.

A 40-year-old Jewish mother may not seem the ideal Hitchcock leading lady, but Katie is vibrant and sexually appealing enough to have drawn the director to this story. And given his apparent delight in placing his actresses in unpleasant circumstances, such as by keeping Madeleine Carroll handcuffed to Robert Donat for long hours each day during the shooting of The 39 Steps, he might have relished the opportunity to place his Katie in some Florida brambles as she tries to elude a killer.

Susan Isaacs writes her thriller with humor and gradually building suspense. We will never discover what Hitchcock might have done with this story, but we can certainly enjoy what Isaacs does with it.

Spy stories, especially those in which ordinary people (often ordinary women with extraordinary beauty) get caught in dangerous situations) were a Hitchcock staple, from The 39 Steps to Torn Curtain. That's what happens in the Isaacs novel. Actually Katie had worked for the CIA, writing mostly routine reports, in her early 20s, but then 15 years ago she had been fired without explanation. Now she writes a successful television series called Spy Guys, but the unfairness of her termination still rankles. So when she gets a call from Lisa, a former CIA colleague, asking for her help and, as bait, promising to reveal the truth about why she was canned, Katie is hooked. But then Lisa never calls back.

Katie wonders if something might have happened to Lisa, but mostly she just wants to get to the bottom of her disgrace of 15 years before. So, her son off to summer camp and her husband preoccupied with his work, she begins making contact with people she worked with at the agency, including her former boss with whom, like many other women in his department, she had had a brief fling. Though a novice at actual espionage, Katie keeps digging until she uncovers the whole complicated truth, nearly at the cost of her life.

A 40-year-old Jewish mother may not seem the ideal Hitchcock leading lady, but Katie is vibrant and sexually appealing enough to have drawn the director to this story. And given his apparent delight in placing his actresses in unpleasant circumstances, such as by keeping Madeleine Carroll handcuffed to Robert Donat for long hours each day during the shooting of The 39 Steps, he might have relished the opportunity to place his Katie in some Florida brambles as she tries to elude a killer.

Susan Isaacs writes her thriller with humor and gradually building suspense. We will never discover what Hitchcock might have done with this story, but we can certainly enjoy what Isaacs does with it.

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

New versions of old stories

Last night I caught a few minutes of The Muppet Christmas Carol on television and marveled once again at how the story written so many years ago by Charles Dickens keeps getting told and retold in so many different forms. A year ago in this space I observed that even the John Mortimer short story Rumpole and the Christmas Spirit, so different from the Dickens tale, can nevertheless be seen as a variation on the Dickens formula. What might Dickens have thought had he been visited by the Ghost of Christmas Future and allowed to see how his creation would evolve over time?

Other classic stories similarly get retold in so many different ways. I am thinking particularly of the Greek myths and the Grimm fairy tales, but there are plenty of other examples. And at Christmas we must also mention the original story, the Nativity, which is still reenacted thousands of times each year at this time, usually with children in the starring roles.

The December issue of Christianity Today includes an article by Sarah Arthur called "Have Yourself a Merry Kitschy Christmas" about the many variations on the basic Nativity set that have been created. Some might strike purists as sacrilegious, such as those featuring superheroes or, in the Meat Nativity, bacon and sausages on a bed of hash browns. This doesn't bother Arthur, however. Whether Wonder Woman or a little girl in her bathrobe portrays Mary doesn't really matter. What's important, as in the case of A Christmas Carol performed by Muppets, is the story itself.

Other classic stories similarly get retold in so many different ways. I am thinking particularly of the Greek myths and the Grimm fairy tales, but there are plenty of other examples. And at Christmas we must also mention the original story, the Nativity, which is still reenacted thousands of times each year at this time, usually with children in the starring roles.

The December issue of Christianity Today includes an article by Sarah Arthur called "Have Yourself a Merry Kitschy Christmas" about the many variations on the basic Nativity set that have been created. Some might strike purists as sacrilegious, such as those featuring superheroes or, in the Meat Nativity, bacon and sausages on a bed of hash browns. This doesn't bother Arthur, however. Whether Wonder Woman or a little girl in her bathrobe portrays Mary doesn't really matter. What's important, as in the case of A Christmas Carol performed by Muppets, is the story itself.

Monday, December 22, 2014

The importance of a good title

Many a new novel has sunk without a trace because it has a dull, unmemorable title.

My wife volunteered to become the librarian at the condominium complex where we are living in Florida. What this means in practice is that I do 90 percent of the work of sorting, organizing and shelving, while she gets 90 percent of the credit.

The books on our shelves have all been donated by residents, and the most popular authors clearly are James Patterson, Nora Roberts, Danielle Steel and a handful of others. While trying to find room for all these books on our shelves I have noticed how dull so many of the titles are. Steel has written Matters of the Heart, Remembrance, Bittersweet, Silent Honor and Sisters. Nora Roberts wrote Change of Heart and Happy Endings. Patterson did Double Cross, Honeymoon and Swimsuit.

Contrast these titles with some by less prominent authors: What the Body Remembers by Shauna Singh Baldwin, The Weight of Silence by Heather Gudenkauf, The Patchwork Marriage by Jane Green and The Light Between the Oceans by M.L. Stedman.

I do not question Susan Hill's conclusion about the importance of a good title, but good titles do seem to be much more important for beginning writers and writers who have never gotten high on best-seller lists. When you have reached the stature of a James Patterson, Nora Roberts or Danielle Steel, apparently, titles don't matter so much. It is the author's name on the cover that sells the book. I do wonder, however, how fans of these authors can remember which of their books they have read and which they haven't.

Susan Hill, Howards End is on the Landing

My wife volunteered to become the librarian at the condominium complex where we are living in Florida. What this means in practice is that I do 90 percent of the work of sorting, organizing and shelving, while she gets 90 percent of the credit.

The books on our shelves have all been donated by residents, and the most popular authors clearly are James Patterson, Nora Roberts, Danielle Steel and a handful of others. While trying to find room for all these books on our shelves I have noticed how dull so many of the titles are. Steel has written Matters of the Heart, Remembrance, Bittersweet, Silent Honor and Sisters. Nora Roberts wrote Change of Heart and Happy Endings. Patterson did Double Cross, Honeymoon and Swimsuit.

Contrast these titles with some by less prominent authors: What the Body Remembers by Shauna Singh Baldwin, The Weight of Silence by Heather Gudenkauf, The Patchwork Marriage by Jane Green and The Light Between the Oceans by M.L. Stedman.

I do not question Susan Hill's conclusion about the importance of a good title, but good titles do seem to be much more important for beginning writers and writers who have never gotten high on best-seller lists. When you have reached the stature of a James Patterson, Nora Roberts or Danielle Steel, apparently, titles don't matter so much. It is the author's name on the cover that sells the book. I do wonder, however, how fans of these authors can remember which of their books they have read and which they haven't.

Friday, December 19, 2014

Strength out of weakness

In her eulogy for Pauline Kael, her daughter, Gina, said, "Pauline's greatest weakness, her failure as a person, became her great strength, her liberation as a writer and a critic." It's an interesting idea, that one's strengths may be attributable to one's weaknesses, but I think it may sometimes be true. It may even be true in my own case.

Kael, who at one time was the most influential film critic in the country, certainly had her weaknesses. Among these was her treatment of her own daughter as a virtual slave, depending upon her to type her reviews, run her errands and provide her transportation, while denying her the freedom to live her own life. Kael's friendships so often depended upon those friends agreeing with her and, at least in the case of other movie critics, not becoming as prominent as she. She allowed herself to be courted by directors and others in the movie business, always insisting a favorable review from her could not be bought, even when so many of her reviews suggested otherwise.

Brian Kellow mentions many other Pauline Kael weaknesses in his 2011 biography Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark, yet the book hardly qualifies as a hatchet job, for his emphasis lies with her significant strengths. She was, whether you agreed with her opinions or not, a terrific writer whose prose jumped off the pages of The New Yorker. Although she rarely wrote about anything other than movies, her reviews managed to be commentary on the times, as well. They were also surprisingly autobiographical. Once urged to write her memoirs, Kael replied, "I think I have."

Writing here a few months back I compared the movie criticism of Kael with that done by novelist Graham Greene back in the 1930s. I noted the similarity in their writing styles, while noting that Kael, at least from her reviews, seemed to be better read than Greene. From her biography I learned that in her youth Kael admired Greene's film criticism and was influenced by his work at the start of her career. As for her reading, I learned that when she heard a movie was going to be based on a novel, she made it a point to read that novel before seeing the film. How many other movie reviewers would go to that much trouble?

Kellow's book nicely summarizes Kael's most important and controversial reviews and articles over the years, yet I think he too often inserts his own opinions about these films, faulting Kael when her opinions don't match his own, which seems to be what he criticizes Kael for doing.

Kael, who at one time was the most influential film critic in the country, certainly had her weaknesses. Among these was her treatment of her own daughter as a virtual slave, depending upon her to type her reviews, run her errands and provide her transportation, while denying her the freedom to live her own life. Kael's friendships so often depended upon those friends agreeing with her and, at least in the case of other movie critics, not becoming as prominent as she. She allowed herself to be courted by directors and others in the movie business, always insisting a favorable review from her could not be bought, even when so many of her reviews suggested otherwise.

Brian Kellow mentions many other Pauline Kael weaknesses in his 2011 biography Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark, yet the book hardly qualifies as a hatchet job, for his emphasis lies with her significant strengths. She was, whether you agreed with her opinions or not, a terrific writer whose prose jumped off the pages of The New Yorker. Although she rarely wrote about anything other than movies, her reviews managed to be commentary on the times, as well. They were also surprisingly autobiographical. Once urged to write her memoirs, Kael replied, "I think I have."

Writing here a few months back I compared the movie criticism of Kael with that done by novelist Graham Greene back in the 1930s. I noted the similarity in their writing styles, while noting that Kael, at least from her reviews, seemed to be better read than Greene. From her biography I learned that in her youth Kael admired Greene's film criticism and was influenced by his work at the start of her career. As for her reading, I learned that when she heard a movie was going to be based on a novel, she made it a point to read that novel before seeing the film. How many other movie reviewers would go to that much trouble?

Kellow's book nicely summarizes Kael's most important and controversial reviews and articles over the years, yet I think he too often inserts his own opinions about these films, faulting Kael when her opinions don't match his own, which seems to be what he criticizes Kael for doing.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Our body's literary needs

I now realize that it is a diary that I have been looking for all over the house ...

Susan Hill devotes a couple of consecutive essays in her book to her search through her house for a book she wanted to read that day. She had no idea what that book might be until she came across some diaries, specifically The Journal of Sir Walter Scott. That, she decided, is what she had been looking for all day without realizing it. "I have found my book," she announces with satisfaction.

Earlier in the day I had been reading Masha Hamilton's wonderful novel The Camel Bookmobile (I will probably have more to say about this later) when I came across, much as Hill did that particular diary, the line where Hamilton's character Fiona Sweeney reflects on the knack so many readers have for finding just the right book at the right time: "Fi was convinced that instinct could determine a body's literary needs, just as physical cravings pointed to dietary shortfalls."

Many of us have probably experienced the same sort of thing, in libraries or bookstores if not in our own homes. We search and search for the right book, and then suddenly, there it is. I have the same kind of experience when I am looking through my DVD collection for just the right movie to watch. Am I in the mood for a drama or a comedy? Am I wide enough awake for a foreign film, where one must read as well as watch and listen? Eventually, like Scott's journal, one movie will jump out at me and I will know that this is the one. It almost always turns out to the best possible choice.

Not every book is the perfect book for every occasion. I wonder about people who read only romances or only mysteries or only self-help books. To me it sounds like having the same thing every day for lunch. How do they meet their "body's literary needs"? Of course, there really is no such thing. Yet like Fiona Sweeney and Susan Hill, I would like to believe there is.

Susan Hill, Howards End is on the Landing

Susan Hill devotes a couple of consecutive essays in her book to her search through her house for a book she wanted to read that day. She had no idea what that book might be until she came across some diaries, specifically The Journal of Sir Walter Scott. That, she decided, is what she had been looking for all day without realizing it. "I have found my book," she announces with satisfaction.

Earlier in the day I had been reading Masha Hamilton's wonderful novel The Camel Bookmobile (I will probably have more to say about this later) when I came across, much as Hill did that particular diary, the line where Hamilton's character Fiona Sweeney reflects on the knack so many readers have for finding just the right book at the right time: "Fi was convinced that instinct could determine a body's literary needs, just as physical cravings pointed to dietary shortfalls."

Many of us have probably experienced the same sort of thing, in libraries or bookstores if not in our own homes. We search and search for the right book, and then suddenly, there it is. I have the same kind of experience when I am looking through my DVD collection for just the right movie to watch. Am I in the mood for a drama or a comedy? Am I wide enough awake for a foreign film, where one must read as well as watch and listen? Eventually, like Scott's journal, one movie will jump out at me and I will know that this is the one. It almost always turns out to the best possible choice.

Not every book is the perfect book for every occasion. I wonder about people who read only romances or only mysteries or only self-help books. To me it sounds like having the same thing every day for lunch. How do they meet their "body's literary needs"? Of course, there really is no such thing. Yet like Fiona Sweeney and Susan Hill, I would like to believe there is.

Monday, December 15, 2014

Slow reading

Too much internet usage fragments the brain and dissipates concentration so that after a while, one's ability to spend long, focused hours immersed in a single subject becomes blunted. Information comes pre-digested in small pieces, one grazes on endless ready-made meals and snacks of the mind, and the result is mental malnutrition.

I am not so sure the internet deserves all the blame for what Susan Hill so aptly calls "mental malnutrition." It seems to me there are plenty of other distractions that make it difficult for us to focus our attention on just one thing: ringing telephones, interruptions by children or spouses or others, other pressing tasks that require our attention, the siren call of our television sets, even computer solitaire. Long before the internet, newspapers and magazines were breaking down information into small pieces.

For many years I wrote in a noisy newsroom, where ringing phones and loud conversations constantly made it challenging to stay focused on one's subject. With a deadline pressing, one simply has to train one's mind to focus. Years later when the number of newsroom personnel had shrunk dramatically, I found the unnatural quiet just as distracting as the noise had once been.

When it comes to reading books, which is the subject at hand in Hill's book, I suspect most of the blame for my own short attention span is my practice of reading several books at one time. I may read but one chapter, or even just a couple of pages in one book before putting it down and picking up another, then doing the same thing with it. There are some books, Susan Hill's Howard's End is on the Landing being one of them, where this kind of reading may be acceptable, even advisable, but most books, whether fiction or nonfiction, deserve longer periods of focus.

Hill writes that by rationing the internet she was able, within a few days, to increase her attention span and tackle difficult long books. "It was like diving into a deep, cool ocean after flitting about in the shallows, Slow Reading as against Gobbling-up," she writes.

It comes down to disciplining ourselves, sort of like learning to write news stories, columns and editorials amid the bustle of a lively newsroom.

Susan Hill, Howard's End is on the Landing

I am not so sure the internet deserves all the blame for what Susan Hill so aptly calls "mental malnutrition." It seems to me there are plenty of other distractions that make it difficult for us to focus our attention on just one thing: ringing telephones, interruptions by children or spouses or others, other pressing tasks that require our attention, the siren call of our television sets, even computer solitaire. Long before the internet, newspapers and magazines were breaking down information into small pieces.

For many years I wrote in a noisy newsroom, where ringing phones and loud conversations constantly made it challenging to stay focused on one's subject. With a deadline pressing, one simply has to train one's mind to focus. Years later when the number of newsroom personnel had shrunk dramatically, I found the unnatural quiet just as distracting as the noise had once been.

When it comes to reading books, which is the subject at hand in Hill's book, I suspect most of the blame for my own short attention span is my practice of reading several books at one time. I may read but one chapter, or even just a couple of pages in one book before putting it down and picking up another, then doing the same thing with it. There are some books, Susan Hill's Howard's End is on the Landing being one of them, where this kind of reading may be acceptable, even advisable, but most books, whether fiction or nonfiction, deserve longer periods of focus.

Hill writes that by rationing the internet she was able, within a few days, to increase her attention span and tackle difficult long books. "It was like diving into a deep, cool ocean after flitting about in the shallows, Slow Reading as against Gobbling-up," she writes.

It comes down to disciplining ourselves, sort of like learning to write news stories, columns and editorials amid the bustle of a lively newsroom.

Wednesday, December 10, 2014

Reading from home

Recently I started reading Susan Hill's 2009 book Howard's End is on the Landing: A Year of Reading from Home. I can see immediately that Hill is going to inspire a lot of reflection on books and reading, so I propose to take her book slowly and use it as a springboard for commentary on this blog over the next few weeks.

I will start with Hill's reason for writing her book in the first place. Looking for one particular book in her home, she found many other books instead. Some she realized she had owned for years but had never read. Others she had read years ago and decided it was time to revisit. She resolved to give up purchasing any new books for a whole year and devote her reading to books she already owned. What follows is a series of short essays about these books and about her reading life, both past and present.

Novelist Susan Hill is a contemporary of mine, just a couple of years older,. At about the same point in life when she decided to focus more attention on her personal library, I was doing much the same thing. I have not taken the step of swearing off new books as Hill did. If anything, I have increased the number of book purchases in recent years. But rarely, except in the case of books sent to me to review, do I ever begin reading a book immediately after acquiring it. Usually I let it age on the shelf for a few years, sometimes 20 years or more. So in one sense I have always been doing what Hill did for her book.

More recently, however, I have been rereading more books I enjoyed a number of years before. This hasn't seemed to decrease my reading of first-time books because, since retirement, I have been able to devote more time for reading. So I have revisited Graham Greene's Monsignor Quixote and Jesse Stuart's The Land Beyond the River, among several other books. Not only have I enjoyed these books a second time, but it has made me feel justified in keeping them for all these years. Some people like to ask, "Why keep books you have already read?" Well, this is why. (Another reason, of course, is reference.)

Thanks to my membership on LibraryThing, I have also, like Hill, spent a lot of time reconsidering every book in my library in the act of cataloging them all for the website. Quite a number of them I decided I really didn't want any more, so I was able to open up some shelf space. Other books surprised me because I had forgotten I even had them. Many books, once I held them in my hands, made me want to open them and start reading again.

I think I am going to like reading about reading in Susan Hill's book.

I will start with Hill's reason for writing her book in the first place. Looking for one particular book in her home, she found many other books instead. Some she realized she had owned for years but had never read. Others she had read years ago and decided it was time to revisit. She resolved to give up purchasing any new books for a whole year and devote her reading to books she already owned. What follows is a series of short essays about these books and about her reading life, both past and present.

Novelist Susan Hill is a contemporary of mine, just a couple of years older,. At about the same point in life when she decided to focus more attention on her personal library, I was doing much the same thing. I have not taken the step of swearing off new books as Hill did. If anything, I have increased the number of book purchases in recent years. But rarely, except in the case of books sent to me to review, do I ever begin reading a book immediately after acquiring it. Usually I let it age on the shelf for a few years, sometimes 20 years or more. So in one sense I have always been doing what Hill did for her book.

More recently, however, I have been rereading more books I enjoyed a number of years before. This hasn't seemed to decrease my reading of first-time books because, since retirement, I have been able to devote more time for reading. So I have revisited Graham Greene's Monsignor Quixote and Jesse Stuart's The Land Beyond the River, among several other books. Not only have I enjoyed these books a second time, but it has made me feel justified in keeping them for all these years. Some people like to ask, "Why keep books you have already read?" Well, this is why. (Another reason, of course, is reference.)

Thanks to my membership on LibraryThing, I have also, like Hill, spent a lot of time reconsidering every book in my library in the act of cataloging them all for the website. Quite a number of them I decided I really didn't want any more, so I was able to open up some shelf space. Other books surprised me because I had forgotten I even had them. Many books, once I held them in my hands, made me want to open them and start reading again.

I think I am going to like reading about reading in Susan Hill's book.

Monday, December 8, 2014

Missing the key words

It annoys my wife when I ask her to repeat something she has just said to me. She thinks I am getting deaf, although if that is true, I have been getting deaf for many years without actually becoming deaf. Part of the problem, I think, is that when my mind is focused on one thing, a book or a football game perhaps, it takes awhile to refocus on something else, namely whatever it is she is saying to me. I have suggested she first make sure she has my attention before telling me something important.

Lately, however, I have come up with a new theory. I usually hear most of what she says, but not the one or two words that would convey the most important information. I might hear the verb but not the noun or, sometimes, the noun but not the verb. Then I noticed I am often missing the key words people other than my wife are saying.

Listening to someone on radio or television (I forget which) count down the top-grossing movies of the weekend, I noticed I could clearly hear almost every word she said except the titles of the movies themselves. The volume of her voice seemed to go down a few notches every time she said a movie title, and it was the titles that were important.

A day or so later I heard another woman, also talking about movies, say, "If you're like me you are obsessed with the movie ...." Again I could clearly hear everything she said except the name of the movie. Later in the conversation, thankfully, I was able to catch the word Frozen, so I finally knew what she was talking about. A few days later I watched Frozen for the first time. It is a wonderful film, although I can't imagine anyone becoming obsessed with it.

Anyway, I am still wondering. Is there something wrong with my hearing or do some people, perhaps even most people, lower their voices slightly when they say key words, as if they are sharing some kind of secret?

Lately, however, I have come up with a new theory. I usually hear most of what she says, but not the one or two words that would convey the most important information. I might hear the verb but not the noun or, sometimes, the noun but not the verb. Then I noticed I am often missing the key words people other than my wife are saying.

Listening to someone on radio or television (I forget which) count down the top-grossing movies of the weekend, I noticed I could clearly hear almost every word she said except the titles of the movies themselves. The volume of her voice seemed to go down a few notches every time she said a movie title, and it was the titles that were important.

A day or so later I heard another woman, also talking about movies, say, "If you're like me you are obsessed with the movie ...." Again I could clearly hear everything she said except the name of the movie. Later in the conversation, thankfully, I was able to catch the word Frozen, so I finally knew what she was talking about. A few days later I watched Frozen for the first time. It is a wonderful film, although I can't imagine anyone becoming obsessed with it.

Anyway, I am still wondering. Is there something wrong with my hearing or do some people, perhaps even most people, lower their voices slightly when they say key words, as if they are sharing some kind of secret?

Friday, December 5, 2014

Take care with commas

He, the pilot and three others had been belted into their seats when the plane went down but two of the passengers had been gripped with hysteria at the first sign of trouble, leaping up and trying to break into the cockpit in their panic.

The use of commas, more so than with other kinds of punctuation, has always been a matter of individual preference. Some writers will use a comma in certain situations, while other writers will leave it out. A case in point is when a sentence lists a series of things. Some writers will write "a lion, a zebra and a gorilla," while others, probably a majority, would write "a lion, a zebra, and a gorilla." Most of the time it matters very little. In the newspaper business we always omitted the comma before the and because it was unnecessary and took up space and, when you are on deadline, time.

The above sentence at the bottom of the first page of Arnaldur Indridason's Icelandic thriller Operation Napoleon caught my attention because its missing comma actually makes a big difference. How many people on the plane were belted into their seats, four or five? The missing second comma makes it clear there were five people wearing their belts and a total of seven people on the plane when it crashed into a glacier. It also makes it clear the man being referred to as he was not the pilot. Were there a second comma we could not be sure about any of this. Commas, both their presence and their absence, can make a huge difference in the meaning of a sentence,

Later in the same sentence, before the word but, Indridason again omits a comma that other writers might have chosen to stick in. It makes little difference either way, but then why use punctuation that doesn't serve a purpose?

Arnaldur Indridason, Operation Napoleon

The use of commas, more so than with other kinds of punctuation, has always been a matter of individual preference. Some writers will use a comma in certain situations, while other writers will leave it out. A case in point is when a sentence lists a series of things. Some writers will write "a lion, a zebra and a gorilla," while others, probably a majority, would write "a lion, a zebra, and a gorilla." Most of the time it matters very little. In the newspaper business we always omitted the comma before the and because it was unnecessary and took up space and, when you are on deadline, time.

The above sentence at the bottom of the first page of Arnaldur Indridason's Icelandic thriller Operation Napoleon caught my attention because its missing comma actually makes a big difference. How many people on the plane were belted into their seats, four or five? The missing second comma makes it clear there were five people wearing their belts and a total of seven people on the plane when it crashed into a glacier. It also makes it clear the man being referred to as he was not the pilot. Were there a second comma we could not be sure about any of this. Commas, both their presence and their absence, can make a huge difference in the meaning of a sentence,

Later in the same sentence, before the word but, Indridason again omits a comma that other writers might have chosen to stick in. It makes little difference either way, but then why use punctuation that doesn't serve a purpose?

Wednesday, December 3, 2014

Art and meaning

Art is a private matter; the artist does it for himself; any work of art that can be understood is the product of a journalist.

from The Dada Manifesto

That idea, popular with so many early in the last century, gets much less support today. Even so, many do believe that art cannot be easy. If too many people understand it, it must not be any good. Perhaps isn't even art at all. Thus, in the world of painting, the likes of Norman Rockwell and Thomas Kinkade get very little credit. In literature, Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch must not be much of a novel because it was a best-seller for so long earlier this year. The fact that many people were never able to finish reading the book they paid $30 for doesn't mitigate the fact that so many others read it and loved it. Popularity lessens artistic value in the eyes of elitists.

My own view is that true art means different things to different people. The best art has an entry level meaning assessable to just about anyone. This is nothing more than simple beauty. A beautiful painting or a beautiful piece of music or a beautifully written novel needs nothing more to justify its existence. If the masses enjoy it, that takes nothing away from it as a work of art.

At the same time, the best art has other levels of understanding that open up to those who may be more perceptive, more intelligent or more experienced. Each reader or observer may find something different. Scholars continue to find new meaning in the works of writers like Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, which were popular with the masses at the time they were written. Much of this meaning may have never been intended by the authors themselves, which means not that the meaning is false but that these novels are true works of art.

The test for The Goldfinch, or any other novel, lies not in how many people bought it or read it or loved it, but rather in how many different levels of meaning will be found, over time, within its pages. The same is true with any work of art.

Friday, November 28, 2014

An insult to P.G. Wodehouse

Sebastian Faulks does P.G. Wodehouse no favors in Jeeves and the Weddings Bells. Intended as an homage to Wodehouse, the first Jeeves and Wooster novel since Wodehouse's last, Aunts Aren't Gentlemen (or The Cat-Nappers), in 1974, seems more like an insult. It lacks the ridiculously complicated plot Wodehouse was known for. More seriously, it lacks the wit.

Sometimes Faulks finds a word or a phrase that sounds authentic, as when he writes "Jeeves shimmied in with the tea tray," but rarely a paragraph or even a complete sentence. As for his chapters, they are too long and never seem to end with any incentive to begin the next one. Jeeves and Wooster novels were never dull, until now.

The early premise of the story is actually quite good. Circumstances oddly call for Jeeves, the manservant, to pretend to be an English lord, while poor Bertie Wooster must play his servant, a wonderful changing of roles that, unfortunately, Faulks never manages to milk for all of its potential humor. The plot, such as it is, involves Bertie trying to aid one of his chums in winning the love of his life and, of course, making a mess of it. Leave it to Jeeves to sort things out in the end, although the resolution seems like something Wodehouse would have never concocted had he written a hundred Jeeves and Wooster novels.

As I've written before, Faulks did a nice job when he paid a similar homage to Ian Fleming in his James Bond novel Devil May Care. His latest tribute novel fails to deliver. But perhaps this is really an homage to Wodehouse after all. It demonstrates that not just anyone, not even a writer as gifted as Sebastian Faulks, can do what he did.

Sometimes Faulks finds a word or a phrase that sounds authentic, as when he writes "Jeeves shimmied in with the tea tray," but rarely a paragraph or even a complete sentence. As for his chapters, they are too long and never seem to end with any incentive to begin the next one. Jeeves and Wooster novels were never dull, until now.

The early premise of the story is actually quite good. Circumstances oddly call for Jeeves, the manservant, to pretend to be an English lord, while poor Bertie Wooster must play his servant, a wonderful changing of roles that, unfortunately, Faulks never manages to milk for all of its potential humor. The plot, such as it is, involves Bertie trying to aid one of his chums in winning the love of his life and, of course, making a mess of it. Leave it to Jeeves to sort things out in the end, although the resolution seems like something Wodehouse would have never concocted had he written a hundred Jeeves and Wooster novels.

As I've written before, Faulks did a nice job when he paid a similar homage to Ian Fleming in his James Bond novel Devil May Care. His latest tribute novel fails to deliver. But perhaps this is really an homage to Wodehouse after all. It demonstrates that not just anyone, not even a writer as gifted as Sebastian Faulks, can do what he did.

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

Short book about a long silence

There's not much to A Fifty-Year Silence: Love, War and a Ruined House in France, as its young author, Miranda Richmond Mouillot, concedes with this summary on the very last page: "Armand and Anna fell in love, bought a house and never spoke again." Her 263-page book details her efforts to discover why Armand and Anna, her maternal grandparents, never spoke again.

There is a bit more to the story. Armand and Anna, both Jews, survived World War II in France, although other family members did not. They saw little of each other during the war. Afterward they married, bought that house and lived together long enough to have a daughter. Then Armand became a translator at the Nuremberg Trials, where he learned firsthand what the Germans did to the Jews. After that, silence. Armand stayed in France. Anna moved to the United States, where years later Miranda was born. Why her grandparents never spoke, yet in some odd way still seemed to love one another, weighed on her mind while she was growing up. Eventually she found that ruined house, spent time with her grandfather and began to piece together the story that neither grandparent wanted to talk about.

Because this story really doesn't amount to much, Mouillot fills out her book with details of her own life, including her romance with and eventual marriage to a Frenchman. She's a fine writer. Not everyone could make so much out of so little and still make it worth reading.

There is a bit more to the story. Armand and Anna, both Jews, survived World War II in France, although other family members did not. They saw little of each other during the war. Afterward they married, bought that house and lived together long enough to have a daughter. Then Armand became a translator at the Nuremberg Trials, where he learned firsthand what the Germans did to the Jews. After that, silence. Armand stayed in France. Anna moved to the United States, where years later Miranda was born. Why her grandparents never spoke, yet in some odd way still seemed to love one another, weighed on her mind while she was growing up. Eventually she found that ruined house, spent time with her grandfather and began to piece together the story that neither grandparent wanted to talk about.

Because this story really doesn't amount to much, Mouillot fills out her book with details of her own life, including her romance with and eventual marriage to a Frenchman. She's a fine writer. Not everyone could make so much out of so little and still make it worth reading.

Friday, November 21, 2014

A revolution at the movies

As in the case with most Academy Awards ceremonies, there was less symbolism to be extracted from the evening than morning-after analysts might have imagined, and even that applied only to the Academy's taste in movies, not to the country's.

The above quotation, found near the end of Pictures at a Revolution, a fascinating 2008 book about the five movies nominated for best picture in 1968, seems like an odd thing for Mark Harris to say, given that his entire book focuses on the symbolism of those five movies and the 1968 Academy Awards. His thesis is that what he calls New Hollywood began to take over from Old Hollywood that year. All five movies nominated -- In the Heat of the Night, The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner and Doctor Doolittle -- were American-made, following a long period of British dominance at awards ceremonies. Younger, liberal, independent film makers, greatly influenced by European directors, began to replace older, conservative studio heads.

The ceremony in 1968, which was delayed by the death of Martin Luther King, reflected the struggle of the two camps, according to Harris. The Graduate and Bonnie and Clyde very much represented New Hollywood, while Doctor Doolittle, the only one of the five films to never break even, represented Old Hollywood. In the Heat of the Night, which won the award for best picture that year, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, were mostly Old Hollywood, but they both starred Sidney Poitier and both dealt with race relations, a timely topic even if the latter film was considered out of date by the time of its release.

Harris goes into exhaustive detail about the making of all five of those movies. Much of his information may be gathered from other sources, yet much of it is also based on his interviews with those involved in the productions. Among the tidbits he shares:

-- French directors Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard both considered directing Bonnie and Clyde. Instead Arthur Penn made the movie and got a nomination for his efforts. It may be a good thing Godard didn't take the job because he wanted to make the movie, set in Texas and surrounding states, in New Jersey in January.

-- Among actresses considered for the part of Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate were Doris Day, Jeanne Moreau, Patricia Neal and Ava Gardner. Anne Bancroft ultimately got the part. And the Simon and Garfunkel song Here's to You Mrs. Robinson was originally written to mention Mrs. Roosevelt.

-- Spencer Tracy's monologue at the end of Guess Who's Coming to Dinner took six days to shoot. Tracy was so ill at at the time he could work just a few hours each day. He died before the movie was released.

--Bosley Crowther, the longtime New York Times movie critic, lost his job because he panned Bonnie and Clyde again and again and again. He loved Cleopatra. Meanwhile, Pauline Kael got her job as film critic at The New Yorker because of an article she wrote praising Bonnie and Clyde.

Oliver!, made in Great Britain, won the Academy Award for best picture the following year, but it was the last British film to win until 1982 (Chariots of Fire). New Hollywood had taken over.

Mark Harris, Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood

The ceremony in 1968, which was delayed by the death of Martin Luther King, reflected the struggle of the two camps, according to Harris. The Graduate and Bonnie and Clyde very much represented New Hollywood, while Doctor Doolittle, the only one of the five films to never break even, represented Old Hollywood. In the Heat of the Night, which won the award for best picture that year, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, were mostly Old Hollywood, but they both starred Sidney Poitier and both dealt with race relations, a timely topic even if the latter film was considered out of date by the time of its release.

Harris goes into exhaustive detail about the making of all five of those movies. Much of his information may be gathered from other sources, yet much of it is also based on his interviews with those involved in the productions. Among the tidbits he shares:

-- French directors Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard both considered directing Bonnie and Clyde. Instead Arthur Penn made the movie and got a nomination for his efforts. It may be a good thing Godard didn't take the job because he wanted to make the movie, set in Texas and surrounding states, in New Jersey in January.

-- Among actresses considered for the part of Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate were Doris Day, Jeanne Moreau, Patricia Neal and Ava Gardner. Anne Bancroft ultimately got the part. And the Simon and Garfunkel song Here's to You Mrs. Robinson was originally written to mention Mrs. Roosevelt.

-- Spencer Tracy's monologue at the end of Guess Who's Coming to Dinner took six days to shoot. Tracy was so ill at at the time he could work just a few hours each day. He died before the movie was released.

--Bosley Crowther, the longtime New York Times movie critic, lost his job because he panned Bonnie and Clyde again and again and again. He loved Cleopatra. Meanwhile, Pauline Kael got her job as film critic at The New Yorker because of an article she wrote praising Bonnie and Clyde.

Oliver!, made in Great Britain, won the Academy Award for best picture the following year, but it was the last British film to win until 1982 (Chariots of Fire). New Hollywood had taken over.

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Naming the states

That so many place names in the United States, especially the names of states and rivers, were derived from indigenous American languages, rather than European languages, seems surprising. Sure we have state names like Rhodes Island, Virginia and Pennsylvania with obvious European roots, yet so many others were taken from Indian words, however corrupted those words may have been in the process.

My own state, Ohio, got its name from an Iroquois word meaning "good river." Michigan comes from a Chippewa word meaning "great water." Massachusetts comes from an Algonquian word, the meaning of which remains unclear although "great hill" is often mentioned. Connecticut got its name from Quinnehtukqut, which means "beside the long tidal river." Oregon may have gotten its name from an Indian name for a river, the Ouragon. Continuing the theme of naming states after Indian words referring to rivers, Mississippi comes from Misi-ziibi, meaning "great river." Idaho was supposedly named for a Shoshone word meaning "gem of the mountains," but this was later found to be a hoax. It was just a made-up word. Oklahoma comes from a Choctaw phrase meaning "red people."

And so it goes. Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Kansas, Alaska and Alabama are among other states whose names had Indian origins.

One of the oddest state name stories may be that of Wyoming, which Elizabeth Little says in Trip of the Tongue "comes from the same language that was spoken in and around what is now New York City." It was first used as a place name in eastern Pennsylvania, where there are towns named Wyoming, Wyomissing and Wyomissing Hills. At least a dozen other states have Wyoming as a place name, as do Ontario, Canada, and New South Wales, Australia. The popularity of the place name, Little writes, has to do with a poem by Thomas Campbell, which contains the line, "On Susquehanna's side, fair Wyoiming!" The word means either "at the big river flat" or "large prairie place," depending upon whom you believe.

|

| Ohio River |

And so it goes. Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Kansas, Alaska and Alabama are among other states whose names had Indian origins.

One of the oddest state name stories may be that of Wyoming, which Elizabeth Little says in Trip of the Tongue "comes from the same language that was spoken in and around what is now New York City." It was first used as a place name in eastern Pennsylvania, where there are towns named Wyoming, Wyomissing and Wyomissing Hills. At least a dozen other states have Wyoming as a place name, as do Ontario, Canada, and New South Wales, Australia. The popularity of the place name, Little writes, has to do with a poem by Thomas Campbell, which contains the line, "On Susquehanna's side, fair Wyoiming!" The word means either "at the big river flat" or "large prairie place," depending upon whom you believe.

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

The remembered victim

It was the crime that people remembered, not the victim.

When I started reading Laura Lippman's 2010 novel I'd Know You Anywhere, I wondered how she was going to make a story -- and knowing Lippman, a riveting story -- when the crimes in question (the abduction and murder of a series of teenage girls) happened years before and the killer sits on death row awaiting his execution. I needn't have worried, for the author pulls it off beautifully, and without relying too heavily on flashbacks.

The key to Lippman's story is that one of Walter Bowman's victims survived. Elizabeth Lerner, now Eliza Benedict, is married and has two children of her own, including a troubled daughter about the same age as she was when she stumbled upon Walter burying one of his victims. He grabbed her and took her with him on his travels. Trying to survive, she cooperated in every way, even to the point of not attempting to escape when she had the chance and aiding in the abduction of another girl, Holly Tackett. Her testimony helped put Walter on death row, where he has been for the past 20 years. But now he has found her again and hopes he can manipulate her as did years before, this time to save his life.

Eliza, who had thought her role in Walter Bowman's murder spree had long been forgotten, finds herself not just pressured by Walter but also caught between two women with opposing agendas. Trudy Tackett, Holly's mother, still blames Eliza for living when her own daughter died, and she wants to make sure Eliza does nothing to keep Walter from his appointment with death. Meanwhile Barbara, a woman who devotes herself to helping violent convicts, pushes Eliza to go along with Walter's scheme. In an author's note at the end of the novel, Lippman writes, "I did my best to make sure that every point of the (death penalty) triangle -- for, against, confused -- was represented by a character who is recognizably human." That she does very well, and all three women are flesh-and-blood characters you can understand, whether you agree with them or not.

Laura Lippman, I'd Know You Anywhere

The key to Lippman's story is that one of Walter Bowman's victims survived. Elizabeth Lerner, now Eliza Benedict, is married and has two children of her own, including a troubled daughter about the same age as she was when she stumbled upon Walter burying one of his victims. He grabbed her and took her with him on his travels. Trying to survive, she cooperated in every way, even to the point of not attempting to escape when she had the chance and aiding in the abduction of another girl, Holly Tackett. Her testimony helped put Walter on death row, where he has been for the past 20 years. But now he has found her again and hopes he can manipulate her as did years before, this time to save his life.

Eliza, who had thought her role in Walter Bowman's murder spree had long been forgotten, finds herself not just pressured by Walter but also caught between two women with opposing agendas. Trudy Tackett, Holly's mother, still blames Eliza for living when her own daughter died, and she wants to make sure Eliza does nothing to keep Walter from his appointment with death. Meanwhile Barbara, a woman who devotes herself to helping violent convicts, pushes Eliza to go along with Walter's scheme. In an author's note at the end of the novel, Lippman writes, "I did my best to make sure that every point of the (death penalty) triangle -- for, against, confused -- was represented by a character who is recognizably human." That she does very well, and all three women are flesh-and-blood characters you can understand, whether you agree with them or not.

Monday, November 10, 2014

Good stories vs. true stories

Good stories trump true stories. What happens with gossip also happens, more often than we might think, with history and the nightly news. Stories are told not necessarily because they are true but simply because they make good stories, which often means they conform with a particular bias.

Elizabeth Little comments on this power of good stories as it applies to language in her enchanting book Trip of the Tongue. The city of Puyallup, Wash., not far from Tacoma, obviously got its name from the Puyalllup Indian tribe from that area, but what does the word actually mean? The popular explanation is that the word means "generous people," and it is easy to see why that story would be popular. You can imagine what the local Chamber of Commerce might be able to do with it.

Yet Little found with a bit of research that the word actually means "bend at the bottom" or perhaps "bottom of the bend," which nicely describes where the city of Puyallup is located along a river. In other words, Puyallup, Wash., means about the same thing as South Bend, Ind. It's just harder to spell and harder to say and, because it is not an English word, opens the door for a better story.

Another example cited by Little has to do with the Chinese word for crisis. For years I have heard speakers point out that this word also means opportunity, the lesson being that a crisis, viewed in the right way, can also be an opportunity for positive change. That's a wonderful story, but Little points out that it's just not true.

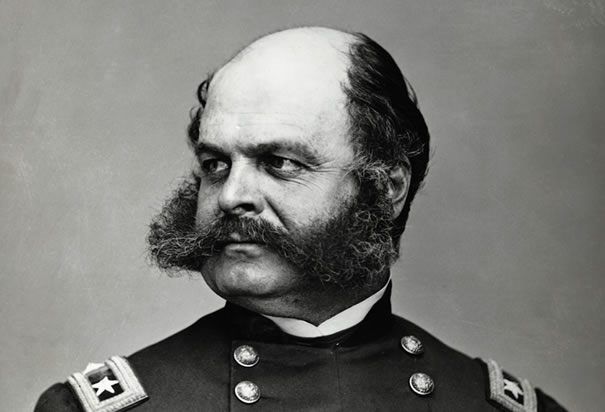

Little's comments made me think of a couple of common words that have both been attributed to Civil War generals: hooker and sideburns. The popular story is that the men serving under Major Gen. Joseph Hooker spent so much of their off-duty time in brothels that prostitutes came to be called hookers. Not true. The slang term has been in use at least since 1845, several years before the Civil War.

As for sideburns, the story has this word going back to Gen. Ambrose Burnside, known for the prominent whiskers on the side of his head. Happily, this story turns out to be true, showing that sometimes, at least, a good story can also be the true story.

Elizabeth Little comments on this power of good stories as it applies to language in her enchanting book Trip of the Tongue. The city of Puyallup, Wash., not far from Tacoma, obviously got its name from the Puyalllup Indian tribe from that area, but what does the word actually mean? The popular explanation is that the word means "generous people," and it is easy to see why that story would be popular. You can imagine what the local Chamber of Commerce might be able to do with it.

Yet Little found with a bit of research that the word actually means "bend at the bottom" or perhaps "bottom of the bend," which nicely describes where the city of Puyallup is located along a river. In other words, Puyallup, Wash., means about the same thing as South Bend, Ind. It's just harder to spell and harder to say and, because it is not an English word, opens the door for a better story.

Another example cited by Little has to do with the Chinese word for crisis. For years I have heard speakers point out that this word also means opportunity, the lesson being that a crisis, viewed in the right way, can also be an opportunity for positive change. That's a wonderful story, but Little points out that it's just not true.

|

| Ambrose Burnside |

As for sideburns, the story has this word going back to Gen. Ambrose Burnside, known for the prominent whiskers on the side of his head. Happily, this story turns out to be true, showing that sometimes, at least, a good story can also be the true story.

Friday, November 7, 2014

Who's in control?

I don't have a very clear idea of who the characters are until they start talking.

The notion that characters, in some sense, write their own stories is probably familiar to anyone who has listened to writers talk about their work. Usually there is at least one novelist at any gathering of writers who reflects on how characters tend to run away with the plot, taking it in new directions the author had never intended.

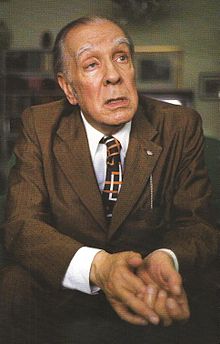

No less a writer than Jorge Luis Borges has said, "Many of the characters are fools and they are always playing tricks on me and treating me badly," suggesting that writing stories becomes something of a wrestling match in which the characters usually manage to pin the author.

I never realized this was a sensitive issue with some writers until I heard novelist Ann Patchett speak at Kenyon College a couple of weeks ago. She made it clear that, for better or worse, she writes her own stories. Her characters are her own creation and they speak only the words she puts into their mouths.

I have since found a couple of quotations from other writers who, more heatedly, say much the same thing.

John Cheever said, "The legend that characters run away from their authors -- taking up drugs, having sex operations, and becoming president -- implies that the writer is a fool with no knowledge or mastery of his craft. The idea of authors running around helplessly behind their cretinous inventions is contemptible."

Vladimir Nabokov put it this way, "The trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is a old as the quills. My characters are galley slaves."

During her Kenyon lecture, Patchett rebelled against another notion that someone or something other than the author might be responsible for the final product. She told the story, also told by novelist Elizabeth Gilbert, about the time the two of them, close friends, were discussing works in progress. Patchett was at that time working on State of Wonder, and Gilbert mentioned she had abandoned her own novel set in the Amazon. When Patchett asked what Gilbert's story was about, Gilbert outlined a plot eerily similar to Patchett's own, about a medical researcher in Minnesota, having an affair with her boss, who must travel to the Amazon.

Gilbert's explanation for this uncanny coincidence was that good ideas travel around the globe looking for receptive minds to bring them to fruition. The Amazon idea first landed on Gilbert, who ultimately rejected it. So the idea moved on to Patchett, who turned it into a great novel.

Patchett cannot explain how she and her friend both had the same idea, but she finds Gilbert's explanation silly. If two people have the same idea at the same time, perhaps it is "an incredibly banal idea," she thought at the time. That can sometimes be true. I recall that back in the early Seventies, two novels about fires in skyscrapers came out at about the same time. They were The Tower by Richard Martin Stern, which I reviewed at the time, and The Inferno, by Thomas M. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson. The two novels were later combined into one movie, The Towering Inferno, which won some Oscars.

In science and discovery it is not that unusual for ideas to strike different people at the same time, as in the case of the invention of the telephone and the theory of evolution. Even so, Patchett and Gilbert both conceiving the same plot for a novel does seem astounding. Perhaps suggesting that ideas travel through space looking for a home, like believing characters write the story themselves, is just a way of explaining the unexplainable.

Joan Didion

|

| Borges |

I never realized this was a sensitive issue with some writers until I heard novelist Ann Patchett speak at Kenyon College a couple of weeks ago. She made it clear that, for better or worse, she writes her own stories. Her characters are her own creation and they speak only the words she puts into their mouths.

I have since found a couple of quotations from other writers who, more heatedly, say much the same thing.

John Cheever said, "The legend that characters run away from their authors -- taking up drugs, having sex operations, and becoming president -- implies that the writer is a fool with no knowledge or mastery of his craft. The idea of authors running around helplessly behind their cretinous inventions is contemptible."

Vladimir Nabokov put it this way, "The trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is a old as the quills. My characters are galley slaves."

During her Kenyon lecture, Patchett rebelled against another notion that someone or something other than the author might be responsible for the final product. She told the story, also told by novelist Elizabeth Gilbert, about the time the two of them, close friends, were discussing works in progress. Patchett was at that time working on State of Wonder, and Gilbert mentioned she had abandoned her own novel set in the Amazon. When Patchett asked what Gilbert's story was about, Gilbert outlined a plot eerily similar to Patchett's own, about a medical researcher in Minnesota, having an affair with her boss, who must travel to the Amazon.

Gilbert's explanation for this uncanny coincidence was that good ideas travel around the globe looking for receptive minds to bring them to fruition. The Amazon idea first landed on Gilbert, who ultimately rejected it. So the idea moved on to Patchett, who turned it into a great novel.

Patchett cannot explain how she and her friend both had the same idea, but she finds Gilbert's explanation silly. If two people have the same idea at the same time, perhaps it is "an incredibly banal idea," she thought at the time. That can sometimes be true. I recall that back in the early Seventies, two novels about fires in skyscrapers came out at about the same time. They were The Tower by Richard Martin Stern, which I reviewed at the time, and The Inferno, by Thomas M. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson. The two novels were later combined into one movie, The Towering Inferno, which won some Oscars.

In science and discovery it is not that unusual for ideas to strike different people at the same time, as in the case of the invention of the telephone and the theory of evolution. Even so, Patchett and Gilbert both conceiving the same plot for a novel does seem astounding. Perhaps suggesting that ideas travel through space looking for a home, like believing characters write the story themselves, is just a way of explaining the unexplainable.

Wednesday, November 5, 2014

The ideal reader

Read as many of the great books as you can before the age of 22.

Last Friday in a post called "A skeptic's view of literature," I observed that for most of us, if we have read the great books or the classics at all, it was likely back when they were assigned reading for high school or college classes. We read them because we had to read them. After our formal education ends, if we read at all (and many college graduates never again open a book) it is much more likely to be something by Michener than Shakespeare or Tolstoy.

Yet two quotations, including the one from James Michener above, make me consider that there may be more to our reading of classics in our youth than just the reading required for English classes. A few days ago while reading an essay on despair by Joyce Carol Oates in the book Deadly Sins, I found this line, "Perhaps the ideal reader is an adolescent: restless, vulnerable, passionate, hungry to learn, skeptical and naive by

turns; with an unquestioned faith in the power of the imagination to change, if not life, one's comprehension of life."

Both Michener and Oates suggest those years before full adulthood may be the best time to read important literature, the best time to absorb it, to be influenced by it and inspired by it. More importantly, it may be the time in our lives when we are the most open to it, the most willing to read these books even when they are just recommended reading, not required reading.

Go into any large bookstore and you are likely to find a table of important books, both old and recent, that seems to be there primarily for adolescent readers. It is probably located in the young adult section of the store. These are not necessarily books that have been assigned in area schools. More likely they are just books adolescents, more than adults, will be drawn to.

I recall that it was in those years before graduation from college that I read so many books that were not necessarily great books but were nevertheless books I had heard about and wondered about, books I thought it might be valuable to read. These included such books as Lord of the Flies, 1984, Brave New World and most of the works of Steinbeck and Salinger. Perhaps it was then, more than any other time of my life, when I was, as Oates suggests, the ideal reader.

James Michener

Yet two quotations, including the one from James Michener above, make me consider that there may be more to our reading of classics in our youth than just the reading required for English classes. A few days ago while reading an essay on despair by Joyce Carol Oates in the book Deadly Sins, I found this line, "Perhaps the ideal reader is an adolescent: restless, vulnerable, passionate, hungry to learn, skeptical and naive by

turns; with an unquestioned faith in the power of the imagination to change, if not life, one's comprehension of life."

Both Michener and Oates suggest those years before full adulthood may be the best time to read important literature, the best time to absorb it, to be influenced by it and inspired by it. More importantly, it may be the time in our lives when we are the most open to it, the most willing to read these books even when they are just recommended reading, not required reading.

Go into any large bookstore and you are likely to find a table of important books, both old and recent, that seems to be there primarily for adolescent readers. It is probably located in the young adult section of the store. These are not necessarily books that have been assigned in area schools. More likely they are just books adolescents, more than adults, will be drawn to.

I recall that it was in those years before graduation from college that I read so many books that were not necessarily great books but were nevertheless books I had heard about and wondered about, books I thought it might be valuable to read. These included such books as Lord of the Flies, 1984, Brave New World and most of the works of Steinbeck and Salinger. Perhaps it was then, more than any other time of my life, when I was, as Oates suggests, the ideal reader.

Monday, November 3, 2014

Sin in the city

The first notable thing about Gary Krist's new book, Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans, may be its subtitle. The main title speaks of sin, yet between sex and murder lies jazz. Jazz?

Well, yes. It turns out that when reformers tried to clean up New Orleans early in the last century, their first target was not prostitution, gambling, booze, corruption or even gangland murders, but dancing. They didn't want women, at least not white women, in places where that new music, sometimes called jazz and sometimes jass, was being played by black musicians. Jazz, played by the likes of Jelly Roll Morton and a still very young Louis Armstrong, drew white audiences to clubs where black musicians played, and reformers found this as objectionable as anything else that was going on in Storyville.

An editorial in the Times-Picayune called "jass" a "form of musical vice" and said, "Its musical value is nil, and its possibilities of harm are great."

Storyville, named for Sidney Story, a New Orleans alderman, was a district of the city where vice was officially tolerated for a number of years. There was also a smaller area that became known as Black Storyville, but black musicians and a few black prostitutes were permitted in Storyville, just not black clientele. The area flourished and fortunes were made by those who owned the businesses, but Storyville was eventually crushed by those seeking reform. Prohibition, which became federal law at the close of World War I, put the final nail in Storyville's coffin. This did not end the sin in New Orleans, of course. It just went into hiding.

Most of the best jazz musicians fled New Orleans, finding more tolerant audiences in Chicago and elsewhere.

As for murder, there was plenty of that in New Orleans at the turn of the century, much of it associated with Italian mobsters. The most feared murderer at the time, the so-called Axeman, was never caught, and his identity remains a mystery to this day, although Krist suspects those killings, too, were mostly gang-related. A burly man broke into homes in the middle of the night and attacked people in their beds with an axe. Most, but not all, of the victims were Italians who owned small grocery stores.

Books about sin and the city have a lure, just like sin and cities themselves. I am thinking particularly of Karen Abbott's Sin and the Second City and Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City, both about Chicago. Krist himself wrote City of Scoundrels, also about Chicago. And just a couple of days ago I saw a similar book about Steubenville, Ohio. Empire of Sin may not be the best book of this kind, but it does make fascinating reading.

Well, yes. It turns out that when reformers tried to clean up New Orleans early in the last century, their first target was not prostitution, gambling, booze, corruption or even gangland murders, but dancing. They didn't want women, at least not white women, in places where that new music, sometimes called jazz and sometimes jass, was being played by black musicians. Jazz, played by the likes of Jelly Roll Morton and a still very young Louis Armstrong, drew white audiences to clubs where black musicians played, and reformers found this as objectionable as anything else that was going on in Storyville.

An editorial in the Times-Picayune called "jass" a "form of musical vice" and said, "Its musical value is nil, and its possibilities of harm are great."