Some things are implicitly understood: you don't eat crisps at the opera and you don't admit that an author beloved by the intelligentsia leaves you cold.

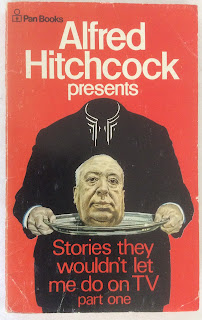

Christopher Fowler, The Book of Forgotten Authors

Several weeks ago I engaged in a fascinating conversation with a man, a retired sanitary engineer as I recall, who was a big Mark Twain admirer, but he argued that Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, not Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is Twain's greatest novel.A Wikipedia article about this book says "critics have not favored Recollections, and it is hardly read or acknowledged in the mainstream today." This makes me admire my momentary friend all the more. Not only was he a brilliant conversationalist on Mark Twain, but he was willing to espouse, and back up, an unpopular point of view.

As Christopher Fowler notes in The Book of Forgotten Authors, most of us hesitate to say anything counter to what the experts say about literature, or anything else for that matter. When is the last time you heard anyone say anything negative about William Shakespeare or James Joyce or William Faulkner or Virginia Woolf or Homer or anyone else esteemed by the intelligentsia? Yet how many of us actually read — and enjoy — these writers? Most of us would rather read Dan Brown or, well, Christopher Fowler.

As Michael Dirda says in Browsings, "We don't read for high-minded reasons. We read for aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual excitement."

It's not that the great writers aren't actually great writers. Rather, tastes differ and we each find our excitement in different places. For the most part, this is no big deal. Barnes & Noble sells a lot of different books, and there is probably something there for everybody. The problem comes when other members of the intelligentsia or literary critics or reviewers bow to more prominent points of view, while burying their own opinions, which may be no less valid.

Who is the greatest living American author? Thankfully, that question remains far from being answered, meaning that there are still many contenders, many points of view and many opportunities for new writers to enter the competition. Only when such questions are answered does the conversation get stifled, making dissenters afraid to speak up.

Which is the greatest Twain novel? The majority view might be Huck Finn, but it's good to know Joan of Arc has a brave champion.