It has been a couple of years since I last did this end-of-the-year meme, the object of which is to answer each question with the title of a book read during the year. The more books one reads, the easier it becomes to answer the questions. I managed to finish 105 books in 2015, so let's see how I do.

Describe Yourself One for the Books (another possible answer: Still Fooling 'Em)

How Do You Feel? Beyond Words (or Wit's End)

Describe Where You Currently Live The New World

If You Could Go Anywhere, Where Would You Go? The Greater Journey

Your Favorite Form of Transportation The Night Train (or Hemingway's Boat)

Your Best Friend Is A Comedy & A Tragedy

You and Your Friends Are Deadline Artists (or Super Boys)

What's the Weather Like Where You Are? Stone Cold

What Is the Best Advice You Could Give? God Guides (or Save the Males)

Thought for the Day Love Wins (or Heads You Lose)

How I Would Like to Die The Big Sleep (or Death in the City of Light)

My Soul's Present Condition A Restless Soul

There, that wasn't so difficult. And a few of the answers even manage to come close to the truth.

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

Monday, December 28, 2015

Speech without words

|

| Bill Murray and Emma Stone |

It seems like a talky movie and, in fact, is one, the Cameron Crowe lines sometimes flying by faster than your mind can grab them. Yet some of the most effective scenes, the ones that will one day bring me back to the movie, are those in which expressions and gestures, not words, carry the story.

As the title suggests, that story is set in Hawaii, home of the hula, a dance in which hand movements express the meaning. The hula becomes the metaphor for the movie, in which various characters use their hands, eyes and facial expressions to carry significant conversations.

We all know, of course, how important body language can be in communication. It's not just the words we say but how we say them. At a restaurant a week ago I noticed a woman on the other side of the room talking with a man. I had no idea what she was saying, but I found her interesting just for the flamboyant manner in which she moved her hands and for the vivid expressions on her face.

I have just started reading American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell by Deborah Solomon. Solomon writes that Rockwell admired Pablo Picasso and at least once actually flirted with abstract art himself. Fortunately he stuck with doing what he did best, painting pictures that told entire stories without benefit of words.

This blog may be dedicated to words, but both Aloha and Norman Rockwell remind me that words do not and cannot convey everything we have to say.

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

The big warm web of books

Each year his school holds a two-day event at the store where kids read favorite books requested by the teachers. I love that he's learned that we each play a role in the big warm web of books: choosing, giving, reading, writing.

Laurent Dubois, who has written books about Haiti and soccer, is among the contributors to My Bookstore, in which writers discuss their favorite places to buy books. His choice is The Regulator Bookshop in Durham, N.C., where he often goes with his son, Anton, nine-years-old when the essay was written.

Both Dubois and his wife may be writers, and thus readers, but he credits The Regulator with welcoming Anton into what he calls "the big warm web of books." I do love that phrase. It speaks of the connections that unite writers and readers, who desperately need each other, as well as booksellers, publishers, librarians, cover illustrators and probably others as well.

Similar connections could be found for virtually any product you might name, such as movies, furniture, food and laundry detergent. Those who consume the product need those who provide the product, and vice versa. But rarely are those other "webs" as warm as the one involving books. Book people, real book people like young Anton, share a passion, not just an interest or a need.

Dubois describes our roles in this web of books as choosing, giving, reading and writing. Each is something each of us, at least each of us who share the passion, can do. Yes, even writing. We may never write a book, but we can write about books. That's what I do in this blog. Others may post reviews on Amazon, LibraryThing or wherever. We can describe our reactions to things we read in our e-mails to friends. Students like Anton write about books in their school essays. Before I began reviewing books back in the early 1970s, I kept a notebook in which I recorded my thoughts about the books I read. I have always found that writing about books helps me understand them better and appreciate them more.

As for choosing and giving, those are something many of us do, especially at this time of year. Rare is the Christmas when I do not give at least one book to a loved one, and usually more. Giving a book requires thoughtful choosing. Often the books we give say more about us than they do those we give the books to. If a friend loves those Chicken Soup books, maybe that's what we should give, not that novel we loved but which the friend may never read. I gave a couple of gift cards this year. Let the readers in my family choose their own books. That's my own ideal Christmas present.

Laurent Dubois, My Bookstore

Laurent Dubois, who has written books about Haiti and soccer, is among the contributors to My Bookstore, in which writers discuss their favorite places to buy books. His choice is The Regulator Bookshop in Durham, N.C., where he often goes with his son, Anton, nine-years-old when the essay was written.

Both Dubois and his wife may be writers, and thus readers, but he credits The Regulator with welcoming Anton into what he calls "the big warm web of books." I do love that phrase. It speaks of the connections that unite writers and readers, who desperately need each other, as well as booksellers, publishers, librarians, cover illustrators and probably others as well.

Similar connections could be found for virtually any product you might name, such as movies, furniture, food and laundry detergent. Those who consume the product need those who provide the product, and vice versa. But rarely are those other "webs" as warm as the one involving books. Book people, real book people like young Anton, share a passion, not just an interest or a need.

Dubois describes our roles in this web of books as choosing, giving, reading and writing. Each is something each of us, at least each of us who share the passion, can do. Yes, even writing. We may never write a book, but we can write about books. That's what I do in this blog. Others may post reviews on Amazon, LibraryThing or wherever. We can describe our reactions to things we read in our e-mails to friends. Students like Anton write about books in their school essays. Before I began reviewing books back in the early 1970s, I kept a notebook in which I recorded my thoughts about the books I read. I have always found that writing about books helps me understand them better and appreciate them more.

As for choosing and giving, those are something many of us do, especially at this time of year. Rare is the Christmas when I do not give at least one book to a loved one, and usually more. Giving a book requires thoughtful choosing. Often the books we give say more about us than they do those we give the books to. If a friend loves those Chicken Soup books, maybe that's what we should give, not that novel we loved but which the friend may never read. I gave a couple of gift cards this year. Let the readers in my family choose their own books. That's my own ideal Christmas present.

Monday, December 21, 2015

I'd rather do it myself

I wouldn't think of buying books at random, without my bookseller's recommendation, no matter how good the reviews may be.

The novelist Isabel Allende, one of dozens of writers who tell about their favorite bookstores in My Bookstore, surprises me. Never buy a book unless one particular bookseller recommends it? How is this even possible, let alone a good idea?

Others contributors to this book express confidence in the recommendations of their favorite booksellers. Novelist Angela David-Gardner writes, "Nancy (Olson) has a genius for matching books and readers. People often ask her, 'What should I read?' She knows her regular customers well enough that she can usually make an immediate suggestion." Well, OK, but isn't that what one might expect from someone who runs a small, independent bookstore? It may be the one clear advantage independent stores have over Barnes & Noble. Yet a suggestion or a recommendation is a long way from never buying a book without someone's suggestion or recommendation. What about whims, impulses, persuasive reviews, comments by friends or simply the fact that if you liked one Isabel Allende novel you might want to read another?

Allende's dependency on her bookseller would, it seems to me, take most of the fun out of shopping for books. I enjoy the search. When you browse the shelves and tables of bookstores, you never know what you might find. And rather than buying exclusively from one bookseller and one bookstore, I enjoy making the rounds to favorite stores, as well as discovering new ones.

I admit something about Allende's trusting relationship with her bookseller appeals to me. I don't recall ever having a close relationship with any bookseller, despite the many hours I spend in bookstores. I envy the fact that someone knows her well enough to know what books may interest her. Even so, my tastes are so diverse that I don't believe I could trust anyone to select my books for me. I wouldn't want someone else to order for me in a restaurant. Why would I want that in a bookstore?

Isabel Allende, My Bookstore

|

| Isabel Allende |

Others contributors to this book express confidence in the recommendations of their favorite booksellers. Novelist Angela David-Gardner writes, "Nancy (Olson) has a genius for matching books and readers. People often ask her, 'What should I read?' She knows her regular customers well enough that she can usually make an immediate suggestion." Well, OK, but isn't that what one might expect from someone who runs a small, independent bookstore? It may be the one clear advantage independent stores have over Barnes & Noble. Yet a suggestion or a recommendation is a long way from never buying a book without someone's suggestion or recommendation. What about whims, impulses, persuasive reviews, comments by friends or simply the fact that if you liked one Isabel Allende novel you might want to read another?

Allende's dependency on her bookseller would, it seems to me, take most of the fun out of shopping for books. I enjoy the search. When you browse the shelves and tables of bookstores, you never know what you might find. And rather than buying exclusively from one bookseller and one bookstore, I enjoy making the rounds to favorite stores, as well as discovering new ones.

I admit something about Allende's trusting relationship with her bookseller appeals to me. I don't recall ever having a close relationship with any bookseller, despite the many hours I spend in bookstores. I envy the fact that someone knows her well enough to know what books may interest her. Even so, my tastes are so diverse that I don't believe I could trust anyone to select my books for me. I wouldn't want someone else to order for me in a restaurant. Why would I want that in a bookstore?

Friday, December 18, 2015

The Yankee we all loved

Many baseball fans hate the New York Yankees because, at least until recent years, they seemed to own October, but was there anyone who didn't love Yogi Berra, the Yankees' human mascot whose 10 World Series rings were the most earned by anyone?

So, however you may feel about the Yankees, you will probably enjoy Driving Mr. Yogi, Harvey Araton's 2013 bestseller that focuses on Berra's later years when, with Ron Guidry, another Yankee great, as his driver, protector, dining partner and best friend, he traveled to Tampa every spring to help the team's catchers prepare for the season ahead.

Berra actually boycotted the Yankees for a number of years, refusing even to attend any games or appear at Old Timers Day, a Yankee institution. When he had been Yankee manager, he expected to be fired one day. Managers always get fired sooner or later, and usually sooner when working for George Steinbrenner. But Berra objected to the way he was fired, through a third party rather than by Steinbrenner face to face, and after a successful season as well. Araton tells how Steinbrenner finally came to Berra, apologized and invited him back into the fold. The old catcher happily relented and was a Yankee for the rest of his life.

Berra, like a lot of old men, was a creature of habit. He liked to eat the same things at the same restaurants on the same day every week, and he wanted to be picked up on time every time. This routine might have driven a lot of companions crazy, but Guidry, whom Berra called Gator because he lives in Louisiana, possessed the right combination of humor, firmness and patience to build a close and lasting relationship. Berra, for all the special privileges he enjoyed, wanted to be treated as just one of the guys, even when he was in his 80s and most of the other guys were in their 20s, and Guidry had the knack for helping the oldtimer fit in.

One reason Berra, who died in September at the age of 90, was so well loved was his many quotable lines, like "When you come to a fork in the road, take it" and "A nickel ain't worth a dime anymore." One of his sons once said of him, "He's the most quoted man in the world, and he never says anything." Yes, he rarely had much to say, but young players learned that when Berra did say something to them, it was worth listening to. He possessed a great baseball mind long after his body began to fail him.

So, however you may feel about the Yankees, you will probably enjoy Driving Mr. Yogi, Harvey Araton's 2013 bestseller that focuses on Berra's later years when, with Ron Guidry, another Yankee great, as his driver, protector, dining partner and best friend, he traveled to Tampa every spring to help the team's catchers prepare for the season ahead.

Berra actually boycotted the Yankees for a number of years, refusing even to attend any games or appear at Old Timers Day, a Yankee institution. When he had been Yankee manager, he expected to be fired one day. Managers always get fired sooner or later, and usually sooner when working for George Steinbrenner. But Berra objected to the way he was fired, through a third party rather than by Steinbrenner face to face, and after a successful season as well. Araton tells how Steinbrenner finally came to Berra, apologized and invited him back into the fold. The old catcher happily relented and was a Yankee for the rest of his life.

Berra, like a lot of old men, was a creature of habit. He liked to eat the same things at the same restaurants on the same day every week, and he wanted to be picked up on time every time. This routine might have driven a lot of companions crazy, but Guidry, whom Berra called Gator because he lives in Louisiana, possessed the right combination of humor, firmness and patience to build a close and lasting relationship. Berra, for all the special privileges he enjoyed, wanted to be treated as just one of the guys, even when he was in his 80s and most of the other guys were in their 20s, and Guidry had the knack for helping the oldtimer fit in.

One reason Berra, who died in September at the age of 90, was so well loved was his many quotable lines, like "When you come to a fork in the road, take it" and "A nickel ain't worth a dime anymore." One of his sons once said of him, "He's the most quoted man in the world, and he never says anything." Yes, he rarely had much to say, but young players learned that when Berra did say something to them, it was worth listening to. He possessed a great baseball mind long after his body began to fail him.

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

A written record

|

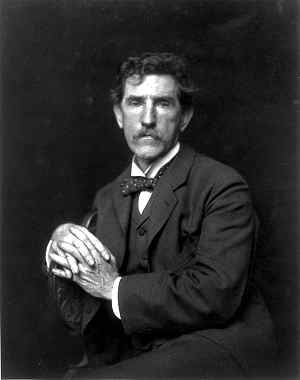

| Augustus Saint-Gaudens |

The answer to my question soon became evident. Washburne, who served in Paris during very turbulent times in the mid-19th century, kept a detailed journal in which he wrote about those times and his own significant role. Saint-Gaudens and, to a greater degree, his wife wrote excellent letters, which survive and provide great source material for any historian or biographer. Sargent and Cassatt apparently wrote less about their own lives, giving future scholars less to write about. What McCullough says about Sargent mostly comes from what friends and art critics said about him.

Winston Churchill was a great man, but I wonder if those long, in some cases multi-volume, biographies of his life are partly due to the fact that he wrote so much about himself, giving his biographers more material than they can fit into a single volume. Meanwhile, William Shakespeare, for all the great plays and sonnets he left behind, apparently wrote little about himself, giving biographers next to nothing to work with.

|

| Mary Chestnut |

Moving closer to home, if you should happen to discover a diary kept by your great-grandmother, or perhaps letters she wrote to a friend over decades, you will know much more about her life than that of any of your other great-grandmothers. Leaving a written record of your life, even if it's nothing more than writing your own obituary and putting it where your children will find it, improves the odds that you and your accomplishments will be remembered.

I wonder about historians and biographers of the future. Will e-mails, texts, blogs and Facebook pages, if they are even available for study, provide the same kind of source material that letters and diaries provide?

Monday, December 14, 2015

Americans in Paris

When I think of American intellectuals in Paris, I think of writers like Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein between the world wars. Yet the appeal of Paris to intelligent, creative Americans began long before that, as David McCullough tells us in his 2011 book The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. He might have gone back to the likes of Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin in the 18th century, but instead McCullough focuses on the period from the late 1830s to about 1900 when Americans in large numbers flocked to Paris, some remaining for years.

These Americans included writers such as James Fenimore Cooper, who wrote some of his best novels in Paris, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry James, but they also included many who traveled to Paris to study art (John Singer Sargent, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Mary Cassatt among them) or medicine (such as Elizabeth Blackwell, America's first female doctor, and Mason Warren). A few went to Paris to study one thing, then became famous for doing something else. Samuel F.B. Morse was there to study art, then invented the telegraph. Oliver Wendell Holmes went to Paris as a medical student but made his reputation in literature.

A few notable Americans in Paris didn't quite fit the usual mold. These included such people as P.T. Barnum, Tom Thumb, White Cloud and Buffalo Bill Cody.

McCullough's book proves to be something of a who's who of important Americans of the 19th century, yet at the same time it becomes a history of 19th century Paris from the perspective of those American visitors. These were trying times for Parisians, with a siege by a Prussian army, the brutal Paris Commune and Louis Napoleon's coup d'etat. Americans were there to witness it all, as well as the world's fairs and the construction of the Eiffel Tower.

McCullough writes readable history, which is why his books become bestsellers. I'm never disappointed with his books, and The Greater Journey certainly does not disappoint.

These Americans included writers such as James Fenimore Cooper, who wrote some of his best novels in Paris, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry James, but they also included many who traveled to Paris to study art (John Singer Sargent, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Mary Cassatt among them) or medicine (such as Elizabeth Blackwell, America's first female doctor, and Mason Warren). A few went to Paris to study one thing, then became famous for doing something else. Samuel F.B. Morse was there to study art, then invented the telegraph. Oliver Wendell Holmes went to Paris as a medical student but made his reputation in literature.

A few notable Americans in Paris didn't quite fit the usual mold. These included such people as P.T. Barnum, Tom Thumb, White Cloud and Buffalo Bill Cody.

McCullough's book proves to be something of a who's who of important Americans of the 19th century, yet at the same time it becomes a history of 19th century Paris from the perspective of those American visitors. These were trying times for Parisians, with a siege by a Prussian army, the brutal Paris Commune and Louis Napoleon's coup d'etat. Americans were there to witness it all, as well as the world's fairs and the construction of the Eiffel Tower.

McCullough writes readable history, which is why his books become bestsellers. I'm never disappointed with his books, and The Greater Journey certainly does not disappoint.

Saturday, December 12, 2015

Science at the seance

"Doesn't he know the scientists are the easiest to fool?"

"It takes a flimflammer to catch a flimflammer."

Stanley (Colin Firth) in Magic in the Moonlight

Harry Houdini

Nearly a century later, it seems amazing that Scientific American once conducted a serious study of mediums and seances and, furthermore, came close to declaring one particular medium the real deal. David Jaher tells about it in a new book, The Witch of Lime Street: Seance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World.

The medium in question was known as Margery, although her real name was Mina Crandon, the wife of a Boston doctor. Other contenders for the cash prize the magazine offered to anyone found to be a true medium were quickly exposed as frauds, but Margery stood up to all the tests the scientists and journalists could throw at her. Enter Harry Houdini, the magician and escape artist, who sat in on some of the seances. He didn't believe Margery for a minute, mainly because he knew how to duplicate most of the effects from her seances, things like floating tables and ringing bells, and he demonstrated them in some of his shows.

Thanks, in part, to Houdini's skepticism, Margery never received the Scientific American prize, yet her career as a spiritualist didn't suffer much. She continued to have faithful supporters, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Although the tests revealed much chicanery in her act, not every amazing feat she performed could be explained, not even by Houdini. Some argued she was a true medium who employed tricks to add theatrics to her performance.

As for the word "seduction" in the subtitle, Margery was an attractive woman who, even in the presence of her husband, used her sex appeal to seduce many of the men who came to expose her. Houdini himself was one of her targets.

I happened to watch the Woody Allen movie Magic in the Moonlight a day or two after finishing The Witch of Lime Street. The film, set at about the same period of history, is about a famous magician determined to prove an amazing medium is a fraud. He is very nearly fooled, at least in part because she is an attractive woman and he wants to believe. Houdini, according to Jaher, wanted to believe, too. He wanted very much to speak with his late mother again. Yet he never fell for Margery's charms or her tricks.

In a book full of amazing detail, Jaher describes a period of history following the Great War, when there was a great desire to communicate with sons and lovers lost in that war. Spiritualists thrived during the 1920s. Houdini, the flimflammer, did as much as anyone to expose the flimflam.

Friday, December 4, 2015

The birth of an idea

Where do you get your ideas?

Writers usually hate to be asked that question, probably because it is a question they are asked so often.Whether we are reading John Grisham's The Firm or Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway, we readers are inclined to wonder where the idea came from. What prompted the writer to write that particular story?

Sometimes we get lucky and authors volunteer their inspiration. Such a case is novelist Tracy Chevalier, best known for Girl With a Pearl Earring. She talks about her idea for the story in another lecture I caught this week on TED.com.

That the novel was inspired by the great Johannes Vermeer painting of the same name should come as no surprise. The story is about the painting of that work, and the painting itself usually appears on covers of the book. Even so, how did the painting provide the idea for the story?

Chevalier says she loves art, but not all art. When she goes to a museum, she says, she usually focuses on just a small number of paintings, those that, in her mind, suggest an untold story. Girl With a Pearl Earring is one such painting. She was delighted to learn, she says, that nobody knows who the girl in the painting was or how Vermeer came to paint her. Thus she was free to imagine and invent.

As she studied the painting, Chevalier says she noticed the "conflicted look" on the face of the girl. Does she feel guilty, ill at ease? Is she in love with the artist? "I wonder what the painter did to her to make her look like that," Chevalier says.

It may be the portrait of one young woman, but the novelist saw it as "a portrait of a relationship." The painting leaves a mystery which the writer sought to solve. She said she looked for "a story to fill in that gap."

The story she wrote, whether true or not, answers the questions she found in the painting. The girl is a pretty servant whose job includes cleaning Vermeer's studio. The painter asks her to pose for him wearing his wife's clothing and earring. The reasons for her conflicted feelings are thoroughly explored.

I love the painting. I love the novel. I love the movie based on the novel. Now I love knowing how Tracy Chevalier got her idea.

Writers usually hate to be asked that question, probably because it is a question they are asked so often.Whether we are reading John Grisham's The Firm or Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway, we readers are inclined to wonder where the idea came from. What prompted the writer to write that particular story?

Sometimes we get lucky and authors volunteer their inspiration. Such a case is novelist Tracy Chevalier, best known for Girl With a Pearl Earring. She talks about her idea for the story in another lecture I caught this week on TED.com.

That the novel was inspired by the great Johannes Vermeer painting of the same name should come as no surprise. The story is about the painting of that work, and the painting itself usually appears on covers of the book. Even so, how did the painting provide the idea for the story?

Chevalier says she loves art, but not all art. When she goes to a museum, she says, she usually focuses on just a small number of paintings, those that, in her mind, suggest an untold story. Girl With a Pearl Earring is one such painting. She was delighted to learn, she says, that nobody knows who the girl in the painting was or how Vermeer came to paint her. Thus she was free to imagine and invent.

As she studied the painting, Chevalier says she noticed the "conflicted look" on the face of the girl. Does she feel guilty, ill at ease? Is she in love with the artist? "I wonder what the painter did to her to make her look like that," Chevalier says.

It may be the portrait of one young woman, but the novelist saw it as "a portrait of a relationship." The painting leaves a mystery which the writer sought to solve. She said she looked for "a story to fill in that gap."

The story she wrote, whether true or not, answers the questions she found in the painting. The girl is a pretty servant whose job includes cleaning Vermeer's studio. The painter asks her to pose for him wearing his wife's clothing and earring. The reasons for her conflicted feelings are thoroughly explored.

I love the painting. I love the novel. I love the movie based on the novel. Now I love knowing how Tracy Chevalier got her idea.

Wednesday, December 2, 2015

Don't talk about it, just do it

Bennett Cerf once said that none of his authors was as good at stirring up publicity as Truman was; the publisher adored the way Truman started talking up a book long before it was finished. He had none of the usual guarded secrecy concerning his work in progress that most authors possessed. Talking about something made it real in his mind, even if he didn't have a word on the page, and so he chattered away happily, dropping hints and tidbits.

The above passage from The Swans of Fifth Avenue, reviewed here a couple of days ago, was still on my mind when I read an item in the December issue of mental_floss magazine about New Year's resolutions. It gives three hints for keeping resolutions, the first of which is, don't tell others about them. "Talking about the person you want to be gives you a premature sense of accomplishment, which hampers your desire to keep working hard," the article says. If you resolve to lose 20 pounds in 2016 and tell your friends about it, they will congratulate you and say, "Way to go." You've already won the praise, so why work so hard to actually lose those 20 pounds?

My wife nearly fell into that trap when, last spring, she noticed some photo albums in the clubhouse of the condo complex where we live in Florida were falling apart. She decided she would place the old photos into new albums when she returned in the fall, and then made the mistake of telling people about it. She was, of course, roundly praised. Over the summer her resolve faded. Nobody looks at these albums from the 1980s and 1990s anyway. Most of those people are now dead. Why bother? I give her credit for showing the grit to follow through on her commitment and tackling those photo albums this fall.

As for Truman Capote, in the last years of his life he loved going on TV talk shows and speaking to journalists about the great novel, Answered Prayers, he was working on. Yet he never completed the book. Some chapters were published in magazines as short stories, but that was as far as he ever got. Talking about the book was so much easier than actually writing it, and in his mind apparently, it produced the same rewards. He did his book tour without having to write the book.

Despite what the late Bennett Cerf and other publishers may think, most writers are wise to say little about their next books until they are finished or nearly finished. I recall speaking with Carla Buckley following the publication of her first novel The Things That Keep Us Here, which I had read and enjoyed. I asked her, what next? She would only say it would be another science/medical thriller about a potentially dangerous environmental threat. Was that saying too much? I don't think so. It made me eager for her next novel, which turned out to be Invisible, without giving too much away. It must have pleased her publisher without actually revealing so much of the story that she was no longer as committed to actually writing it.

Melanie Benjamin, The Swans of Fifth Avenue

|

| Truman Capote |

My wife nearly fell into that trap when, last spring, she noticed some photo albums in the clubhouse of the condo complex where we live in Florida were falling apart. She decided she would place the old photos into new albums when she returned in the fall, and then made the mistake of telling people about it. She was, of course, roundly praised. Over the summer her resolve faded. Nobody looks at these albums from the 1980s and 1990s anyway. Most of those people are now dead. Why bother? I give her credit for showing the grit to follow through on her commitment and tackling those photo albums this fall.

As for Truman Capote, in the last years of his life he loved going on TV talk shows and speaking to journalists about the great novel, Answered Prayers, he was working on. Yet he never completed the book. Some chapters were published in magazines as short stories, but that was as far as he ever got. Talking about the book was so much easier than actually writing it, and in his mind apparently, it produced the same rewards. He did his book tour without having to write the book.

| Carla Buckley |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)