Donald E. Westlake a science fiction writer? Well, yes. We know him as a prolific author of modern crime novels, some deadly serious (the Parker books) and others hilariously funny (the Dortmunder books). But Westlake, who died in 2008, did dabble in sci-fi, selling stories to such magazines as Amazing and Galaxy. Nine of these stories, plus a short sci-fi novel called Anarchaos, were collected in Tomorrow's Crimes and published in 1989.

Most of these tales read like Westlake's crime stories transplanted into space or into the future. In one, "The Risk Profession," an insurance claims investigator is sent to an asteroid where a prospector has died soon after making a strike. Was the death really accidental or did his partner murder him?

Yet several of these stories have inventive twists that suggest that, had he wanted, Westlake might have become a first-rate sci-fi writer. In "The Spy in the Elevator," years after a global disaster survivors are still living in giant buildings, each an independent culture and each distrustful of those living in other buildings. One day a "spy" from another building is found in an elevator, and he has something disturbing to say. What's most disturbing is that he may be right.

Anarchaos is clearly the best of these tales. The novel finds Rolf Malone, recently released from prison on Earth, going to the planet Anarchaos to discover why his brother, Gar, has died. The planet's name describes conditions there. Rolf finds anarchy and chaos. Only the fittest survive. His brother was not among them. How about Rolf? A group of men think Gar, as in "The Risk Profession," had made a valuable mining discovery. He left behind a coded message, and they believe Rolf to be the only person able to read it. They will go to any lengths to get him to reveal the secret.

Westlake makes Anarchaos a planet where, like the Earth's moon, one side is always in light and the other in darkness. He uses this feature creatively throughout the story to add to the tension. Another sci-fi twist is a drug called antizone that forces a person to reveal everything he knows while at the same time wiping his memory clean. At one point, eager to forget, Rolf welcomes this drug.

Eventually Rolf decides the entire planet is evil and must be destroyed. The irony is that in his quest he has left a trail of corpses behind, suggesting that if he can manage to leave Anarchaos, the evil will leave with him.

Friday, September 30, 2016

Wednesday, September 28, 2016

Shades of meaning

My wife and I had a brief conversation recently about one of her feet. I described it as a "sore foot." She corrected me, saying it was an "aching foot."

I have before me an old book called The Synonym Finder, a handier version of Roget's Thesaurus. I had this book on my desk for much of my career, and I continue to consult it on occasion. A synonym is, by definition, a word that means the same thing as another word. Yet as the exchange with my wife illustrated, synonyms aren't always synonymous. Different words, however close they may be in meaning, often mean slightly different things to different people in different situations.

The word sore may have suggested a more severe pain than my wife was experiencing, so she favored aching as the better choice. Or it may have suggested a less severe pain or an external pain rather than an internal pain or some other shade of meaning. I just know that one word correctly described how her foot felt, and the other didn't.

Here are some other synonyms for sore listed in The Synonym Finder: painful, tender, sensitive, raw, smarting, stinging, burning, inflamed, irritated, achy and hurting. You may have used each of these terms to describe a pain, but chances are you have never used all of them to describe the same pain. A stinging pain is quite different from a sensitive pain, which is not the same as an achy pain.

Or take the word stop. Suggested synonyms include pause, desist, cease, halt and quit. Yet each of these words suggests something a little different. A pause, for example, sounds temporary, while quit seems permanent. Words like desist, cease and halt sound more intimidating. The phrase cease and desist implies the two words don't mean the same thing. A border guard might say halt, but the rest of us don't use it much. We probably would be confused if an octagonal sign used any word other than STOP.

The English language has so many words that mean almost the same thing because it has adopted words from so many different sources: Anglo-Saxon, Norse, French, Latin and Greek, to name the main ones. Other languages may be purer, in the sense of being less influenced by other languages, and that can make finding the right word so much easier. There just are not as many options. English vocabulary, however, allows any number of nuanced meanings so that we can say we have a sore foot or an aching foot and

not necessarily mean the same thing.

I have before me an old book called The Synonym Finder, a handier version of Roget's Thesaurus. I had this book on my desk for much of my career, and I continue to consult it on occasion. A synonym is, by definition, a word that means the same thing as another word. Yet as the exchange with my wife illustrated, synonyms aren't always synonymous. Different words, however close they may be in meaning, often mean slightly different things to different people in different situations.

The word sore may have suggested a more severe pain than my wife was experiencing, so she favored aching as the better choice. Or it may have suggested a less severe pain or an external pain rather than an internal pain or some other shade of meaning. I just know that one word correctly described how her foot felt, and the other didn't.

Here are some other synonyms for sore listed in The Synonym Finder: painful, tender, sensitive, raw, smarting, stinging, burning, inflamed, irritated, achy and hurting. You may have used each of these terms to describe a pain, but chances are you have never used all of them to describe the same pain. A stinging pain is quite different from a sensitive pain, which is not the same as an achy pain.

Or take the word stop. Suggested synonyms include pause, desist, cease, halt and quit. Yet each of these words suggests something a little different. A pause, for example, sounds temporary, while quit seems permanent. Words like desist, cease and halt sound more intimidating. The phrase cease and desist implies the two words don't mean the same thing. A border guard might say halt, but the rest of us don't use it much. We probably would be confused if an octagonal sign used any word other than STOP.

The English language has so many words that mean almost the same thing because it has adopted words from so many different sources: Anglo-Saxon, Norse, French, Latin and Greek, to name the main ones. Other languages may be purer, in the sense of being less influenced by other languages, and that can make finding the right word so much easier. There just are not as many options. English vocabulary, however, allows any number of nuanced meanings so that we can say we have a sore foot or an aching foot and

not necessarily mean the same thing.

Monday, September 26, 2016

Great readers don't need lists

But the problem with reading lists ... is that they are all in a sense dead letters, guides for the unadventurous, those without the time or the ambition to hunt around and make discoveries for themselves. The great readers will always know about books that neither the marketplace nor the academy has got around to.

There are great books, and there are great readers. Eventually they will find each other. So Larry McMurtry seems to be saying, and I think he's right.

I share his distaste for reading lists, which can come in a variety of forms. McMurtry makes a distinction between the marketplace and the academy, and so will I. The most obvious marketplace reading lists are those listing bestselling books. Many bookstores even discount bestsellers, giving people an incentive to buy them, thus helping bestselling books remain bestselling books. When these books are eventually published in paperback, their covers will have something like "New York Times bestseller" on the front as a guide for those who prefer to buy books that many others have read and presumably liked. Great readers don't care what other people are reading.

Bookstores may also have displays of staff recommendations, classic books, "books everyone should read" and so forth. Such displays are forms of reading lists.

As for academy reading lists, these would include recommendations by teachers, such as for summer reading, and college professors. Academics also write books and articles discussing books of note, and these can be influential with a certain audience.

Reading lists can take other forms, as well. Reading clubs tell members what to read. Book reviewers make recommendations and often provide a year-end list of the best books. Book blogs, my own included, suggest certain books. Then there are those books with titles like 1,001 Books You Must Read Before You Die.

I don't always ignore reading lists, whatever their form, but I rarely use them as guides for what I should be reading. Rather I just like comparing the lists against my own lists of books read and books I want to read. I love it when a book I enjoyed makes it to someone else's list. And on rare occasions I may even decide a book on someone's list looks interesting and so decide to read it. Great readers don't need reading lists to find great books, but lists can be one more way in which great books can be discovered. A book on a reading list isn't necessarily a bad book anymore than it is necessarily a great book. Great readers just like to decide for themselves.

Larry McMurtry, Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen

There are great books, and there are great readers. Eventually they will find each other. So Larry McMurtry seems to be saying, and I think he's right.

I share his distaste for reading lists, which can come in a variety of forms. McMurtry makes a distinction between the marketplace and the academy, and so will I. The most obvious marketplace reading lists are those listing bestselling books. Many bookstores even discount bestsellers, giving people an incentive to buy them, thus helping bestselling books remain bestselling books. When these books are eventually published in paperback, their covers will have something like "New York Times bestseller" on the front as a guide for those who prefer to buy books that many others have read and presumably liked. Great readers don't care what other people are reading.

Bookstores may also have displays of staff recommendations, classic books, "books everyone should read" and so forth. Such displays are forms of reading lists.

As for academy reading lists, these would include recommendations by teachers, such as for summer reading, and college professors. Academics also write books and articles discussing books of note, and these can be influential with a certain audience.

Reading lists can take other forms, as well. Reading clubs tell members what to read. Book reviewers make recommendations and often provide a year-end list of the best books. Book blogs, my own included, suggest certain books. Then there are those books with titles like 1,001 Books You Must Read Before You Die.

I don't always ignore reading lists, whatever their form, but I rarely use them as guides for what I should be reading. Rather I just like comparing the lists against my own lists of books read and books I want to read. I love it when a book I enjoyed makes it to someone else's list. And on rare occasions I may even decide a book on someone's list looks interesting and so decide to read it. Great readers don't need reading lists to find great books, but lists can be one more way in which great books can be discovered. A book on a reading list isn't necessarily a bad book anymore than it is necessarily a great book. Great readers just like to decide for themselves.

Friday, September 23, 2016

Moments of memory

That's the basic difference between price and value: one is calculated in dollars, the other in moments of memory.

When buying or selling homes, cars, toys, furniture or almost any kind of physical object, price and value can potentially come into conflict. The price we are willing to pay or accept as payment may depend upon the value we place on the object because of what Wendy Welch calls "moments of memory." Objects associated in our minds with good memories have more value to us. To buy them, we are willing to pay a higher price. To sell them, we may demand a higher price.

Welch is specifically talking about books. As the owner of a small used bookstore, she recognizes that persons thinking of selling books to create more space in their homes may find it difficult to part with certain books because of the memories attached to them, while customers seeking to replace books they loved in their youth may be willing to pay more than the books are actually worth.

Most of us who have books have at least some of them chiefly because of the memories attached them. They may be worthless in the marketplace, and we may never want to read them again. Yet they are priceless to us, or at least those "moments of memory" are priceless.

I still have a vocabulary book I spent hours with as a child. It shows pictures of ordinary objects with the appropriate word under each. I don't know whether my lifelong interest in words stemmed from that book or whether my interest in that book stemmed from some innate love for words. In any case, that is one of my priceless books.

Another is The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood by Howard Pyle, illustrated by Lawrence Beall Smith. How I loved that book. Today I can't see it on the shelf without sweet memories being triggered.

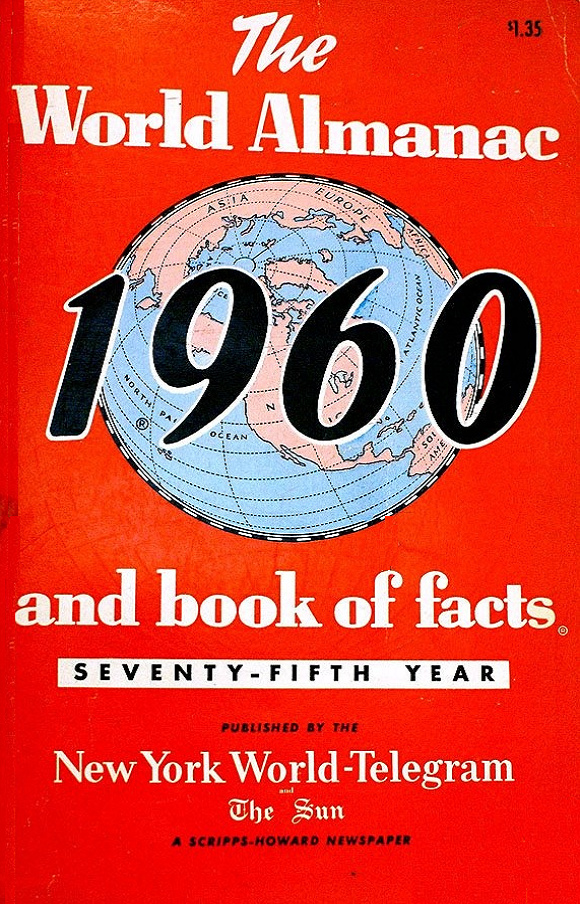

I also have a battered paperback copy of the 1960 World Almanac that I shall never surrender. Today the fine print in that 896-page book is difficult for me to read, but in high school I loved opening it to a random page to see what bits of information I could discover. Let's try it now: "The National Geographic Society, Washington 6, D.C., was organized in 1888 'for the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge.'" And again: "A Knot is a measure of speed, one knot being a speed of one nautical mile an hour." This book cost $1.35, and I never felt that I needed another, newer edition.

Look through your own library. You will likely find books that have great value to you and books you might sell for a good price. Chances are they will not be the same books.

Wendy Welch, The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap

Welch is specifically talking about books. As the owner of a small used bookstore, she recognizes that persons thinking of selling books to create more space in their homes may find it difficult to part with certain books because of the memories attached to them, while customers seeking to replace books they loved in their youth may be willing to pay more than the books are actually worth.

Most of us who have books have at least some of them chiefly because of the memories attached them. They may be worthless in the marketplace, and we may never want to read them again. Yet they are priceless to us, or at least those "moments of memory" are priceless.

I still have a vocabulary book I spent hours with as a child. It shows pictures of ordinary objects with the appropriate word under each. I don't know whether my lifelong interest in words stemmed from that book or whether my interest in that book stemmed from some innate love for words. In any case, that is one of my priceless books.

Another is The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood by Howard Pyle, illustrated by Lawrence Beall Smith. How I loved that book. Today I can't see it on the shelf without sweet memories being triggered.

I also have a battered paperback copy of the 1960 World Almanac that I shall never surrender. Today the fine print in that 896-page book is difficult for me to read, but in high school I loved opening it to a random page to see what bits of information I could discover. Let's try it now: "The National Geographic Society, Washington 6, D.C., was organized in 1888 'for the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge.'" And again: "A Knot is a measure of speed, one knot being a speed of one nautical mile an hour." This book cost $1.35, and I never felt that I needed another, newer edition.

Look through your own library. You will likely find books that have great value to you and books you might sell for a good price. Chances are they will not be the same books.

Wednesday, September 21, 2016

Good news/bad news

Why would you write a poem about that dirty old Henry Hill and Father's overcoat? Aren't there nicer things to write about?

Early in Richard B. Wright's novel Clara Callan, Clara sends her sister, Nora, a poem she has written about the town drunk now wearing their late father's overcoat. The poem includes the lines "That sombre banker's coat/Now the glad rags/Of a foolish man." That brings the above reply, where Nora suggests her older sister write poems about "nicer things."

Writing about nicer things is what Clara does in her letters to her sister for most of the rest of the novel. Her life falls into turmoil. She is raped by a tramp and later has a doomed affair with a married man, yet Clara writes letters full of the kind of happy news she thinks her sister wants to hear. That is until desperation forces Clara to share her bad news. Nora, of course, then scolds her sister for not confiding the bad news earlier.

The phrase "I've got some good news and some bad news" is the start of many a joke. Yet it also describes the dilemma most of us often face when we write a letter (or, more likely, an e-mail), talk with a friend or even write a poem or a story. Should we focus on the positive or the negative? Should we ignore the bad news altogether?

We tend to admire people with stiff upper lips who, however much they may suffer, just don't talk about it, while avoiding those who seem to complain all the time. We like to be around those who, as the Carter Family song goes, "keep on the sunny side of life." Yet life, like any street, does have two sides, and both sides need attention. It can be a mistake to ignore either our blessings or our problems.

During my long newspaper career I heard frequent complaints that newspapers print only the bad news. I never thought this to be true, for newspapers print much good news, even on their front pages. Rather people seem to read and remember the bad news more than the good news. Stories about murders and plane crashes are just more interesting than those about science fair winners and people with unusual hobbies. If a newspaper ever failed to report a rape or murder in their own neighborhood, those people who complain about too much bad news would probably be among the first to protest.

Like newspapers, we should be willing to report both our good news and bad news, at least to those willing to receive it.

Richard B. Wright, Clara Callan

|

| Richard B. Wright |

Writing about nicer things is what Clara does in her letters to her sister for most of the rest of the novel. Her life falls into turmoil. She is raped by a tramp and later has a doomed affair with a married man, yet Clara writes letters full of the kind of happy news she thinks her sister wants to hear. That is until desperation forces Clara to share her bad news. Nora, of course, then scolds her sister for not confiding the bad news earlier.

The phrase "I've got some good news and some bad news" is the start of many a joke. Yet it also describes the dilemma most of us often face when we write a letter (or, more likely, an e-mail), talk with a friend or even write a poem or a story. Should we focus on the positive or the negative? Should we ignore the bad news altogether?

We tend to admire people with stiff upper lips who, however much they may suffer, just don't talk about it, while avoiding those who seem to complain all the time. We like to be around those who, as the Carter Family song goes, "keep on the sunny side of life." Yet life, like any street, does have two sides, and both sides need attention. It can be a mistake to ignore either our blessings or our problems.

During my long newspaper career I heard frequent complaints that newspapers print only the bad news. I never thought this to be true, for newspapers print much good news, even on their front pages. Rather people seem to read and remember the bad news more than the good news. Stories about murders and plane crashes are just more interesting than those about science fair winners and people with unusual hobbies. If a newspaper ever failed to report a rape or murder in their own neighborhood, those people who complain about too much bad news would probably be among the first to protest.

Like newspapers, we should be willing to report both our good news and bad news, at least to those willing to receive it.

Monday, September 19, 2016

Small-town secrets

What we may think of as simpler times weren't really all that simple, at least not to those living in those times. So Canadian writer Richard B. Wright makes clear in his absorbing 2002 novel Clara Callan. Set during the years from 1934 to 1938, Wright's characters wrestle with confusing new technology like party-line telephones, home entertainment delivered via radio, long-distance air transportation and the conversion of coal furnaces to oil. And as for personal relationships, well they were certainly as complex then as now.

Clara Callan is a young school teacher, introverted and unmarried, in an Ontario village a few miles outside of Toronto. Her younger sister, Nora, more beautiful and outgoing than Clara, has just moved to New York City and very quickly become a star on a popular radio soap opera. The entire novel is told through Clara's diary entries during those years and in letters exchanged between the two sisters and with a few other characters.

Clara's quiet life is disrupted when she is raped while walking along some railroad tracks. When she discovers she is pregnant, she enlists Nora's help, without telling her how the pregnancy happened, in getting an abortion in New York. Wright leaves hints that Clara might seek revenge against the man who raped her, as she seeks him out and stalks him, but then she meets a man in a Toronto theater and, for the first time in her life, falls in love. Of course, Frank turns out to be married. And so this bland schoolteacher has another secret she must hide from the nosy people of her village, made all the more difficult when she gets one of those party-line telephones.

How this timid teacher ultimately becomes the bravest, if not the wisest, resident of her village makes fine reading.

Clara Callan is a young school teacher, introverted and unmarried, in an Ontario village a few miles outside of Toronto. Her younger sister, Nora, more beautiful and outgoing than Clara, has just moved to New York City and very quickly become a star on a popular radio soap opera. The entire novel is told through Clara's diary entries during those years and in letters exchanged between the two sisters and with a few other characters.

Clara's quiet life is disrupted when she is raped while walking along some railroad tracks. When she discovers she is pregnant, she enlists Nora's help, without telling her how the pregnancy happened, in getting an abortion in New York. Wright leaves hints that Clara might seek revenge against the man who raped her, as she seeks him out and stalks him, but then she meets a man in a Toronto theater and, for the first time in her life, falls in love. Of course, Frank turns out to be married. And so this bland schoolteacher has another secret she must hide from the nosy people of her village, made all the more difficult when she gets one of those party-line telephones.

How this timid teacher ultimately becomes the bravest, if not the wisest, resident of her village makes fine reading.

Friday, September 16, 2016

Virtual living

When four young adults emigrate from Russia to New York City, their lives remain tied together in Lara Vapnyar's novel Still Here, even when they strive to go their separate ways. Regina marries a successful American businessman, then spends her days eating and watching television, preferably both at the same time. Vidik floats from one job to another, unable to keep any of them for long. Vica is a medical technician but wants something better. She is married to Sergey, formerly Regina's boyfriend, who is obsessed with his idea for an app. If only he can find someone willing to invest money in it.

It is this app that holds the center of the plot. He calls it Virtual Grave. Its purpose is to give people an online presence even after death. They could, for example, continue to "like" things on Facebook that they would have liked while still living. "Our online presence is where the essence of a person is nowadays," Sergey says early in the novel. He views his app as a form of immortality.

Vapnyar's returns to Virtual Grave again and again until it becomes clear her characters, with all their interest in virtual death, are actually living virtual lives. They sometimes long to return to Moscow perhaps because their lives there had seemed more real somehow. Now they float from job to job, from romance to romance, from fad to fad, without anything actually anchoring them to the real world.

Other apps mentioned in the story reenforce this idea. There is one called Eat'n'Watch, which suggests the best food to eat while watching certain TV shows and tells you where to get it in your neighborhood. Virtual Suitcase offers a place on the web to store memorabilia like photos, videos and important e-mail. Online one can have virtual friends and even virtual lovers.

How each of her characters comes to embrace real life, in different ways, is what Still Here is about.

It is this app that holds the center of the plot. He calls it Virtual Grave. Its purpose is to give people an online presence even after death. They could, for example, continue to "like" things on Facebook that they would have liked while still living. "Our online presence is where the essence of a person is nowadays," Sergey says early in the novel. He views his app as a form of immortality.

Vapnyar's returns to Virtual Grave again and again until it becomes clear her characters, with all their interest in virtual death, are actually living virtual lives. They sometimes long to return to Moscow perhaps because their lives there had seemed more real somehow. Now they float from job to job, from romance to romance, from fad to fad, without anything actually anchoring them to the real world.

Other apps mentioned in the story reenforce this idea. There is one called Eat'n'Watch, which suggests the best food to eat while watching certain TV shows and tells you where to get it in your neighborhood. Virtual Suitcase offers a place on the web to store memorabilia like photos, videos and important e-mail. Online one can have virtual friends and even virtual lovers.

How each of her characters comes to embrace real life, in different ways, is what Still Here is about.

Wednesday, September 14, 2016

Multi-dimensional books on one-dimensional shelves

"The problem of the librarian is that books are multi-dimensional in their subject matter but must be ordered on one-dimensional shelves."

If you have ever attempted to shelve your own books in an organized way, you know the problem. Some books can be extremely difficult to categorize.I touched on the problem a year ago (Sept. 28, 2015) in a post called "Staying put" about Vivian Swift's book When Wanderers Cease to Roam. Is this, I asked, a travel book, a memoir, a journal, an art book or a book about natural history? Well, yes. And it's about many other things as well. So on what shelf so you place it so you can find it again? This explains why I now have no idea where the book is in my library.

The speaker in Neal Stephenson's novel is Gottfried Leibniz, a 17th century German mathematician. He is speaking to Nicolas Fatio de Dullier, a 17th century Swiss mathematician. So naturally when talking about how to shelve books, they seek a mathematical solution. Leibniz's idea, at least in the novel, is to assign each author and each subject a number. Multiply the author number by the subject number and you get a number that determines the book's placement in the library.

According to his example, Plato's number is 2, Aristotle's number is 3, trees are assigned the number 5 and turtles get the number 7. Thus, if Plato writes a book about trees, it would be assigned the number 10, and if Aristotle writes about turtles, it would get the number 21. Obvious problems present themselves, in addition to those of assigning numbers to every writer and every subject and the requirement that every librarian also be a mathematician. If Plato then writes about turtles (14) and Aristotle writes about trees (15), the two turtle books would not be side by side on the shelf, nor would the two books about trees. Furthermore, what do you do if either Plato or Aristotle writes a book about turtles under trees? Or what number would you assign to Vivian Swift's book about so many different subjects?

The Dewey Decimal System, created by Melvil Dewey in 1876, did in fact find a way to assign a number to every book. These numbers had the advantage of grouping books about turtles on one shelf and books about trees on another shelf. As for books about turtles resting under trees, assuming that turtles ever prefer trees to direct sunlight, there was a card catalog for cross-referencing.

Now, thanks to computers, it is possible to do the kind of things Leibniz, early inventor of mechanical calculators, could only dream of. Feed into a computer what you are looking for, and it will tell you where to find relevant books on library shelves. Those of us who do not have our home libraries computerized, however, may still experience the kind of confusion Leibniz and Fatio share in The Confusion.

Neal Stephenson, The Confusion

If you have ever attempted to shelve your own books in an organized way, you know the problem. Some books can be extremely difficult to categorize.I touched on the problem a year ago (Sept. 28, 2015) in a post called "Staying put" about Vivian Swift's book When Wanderers Cease to Roam. Is this, I asked, a travel book, a memoir, a journal, an art book or a book about natural history? Well, yes. And it's about many other things as well. So on what shelf so you place it so you can find it again? This explains why I now have no idea where the book is in my library.

|

| Gottfried Leibniz |

According to his example, Plato's number is 2, Aristotle's number is 3, trees are assigned the number 5 and turtles get the number 7. Thus, if Plato writes a book about trees, it would be assigned the number 10, and if Aristotle writes about turtles, it would get the number 21. Obvious problems present themselves, in addition to those of assigning numbers to every writer and every subject and the requirement that every librarian also be a mathematician. If Plato then writes about turtles (14) and Aristotle writes about trees (15), the two turtle books would not be side by side on the shelf, nor would the two books about trees. Furthermore, what do you do if either Plato or Aristotle writes a book about turtles under trees? Or what number would you assign to Vivian Swift's book about so many different subjects?

The Dewey Decimal System, created by Melvil Dewey in 1876, did in fact find a way to assign a number to every book. These numbers had the advantage of grouping books about turtles on one shelf and books about trees on another shelf. As for books about turtles resting under trees, assuming that turtles ever prefer trees to direct sunlight, there was a card catalog for cross-referencing.

Now, thanks to computers, it is possible to do the kind of things Leibniz, early inventor of mechanical calculators, could only dream of. Feed into a computer what you are looking for, and it will tell you where to find relevant books on library shelves. Those of us who do not have our home libraries computerized, however, may still experience the kind of confusion Leibniz and Fatio share in The Confusion.

Monday, September 12, 2016

Deep but never obscure

The prose was dense, with a thorough absence of clarity, no clearings, no cracks that would allow even the thinnest ray of light, no loopholes, no compromises. You had to respect the guy.

(A)lmost all the best novelists can be read by the interested and committed reader. However great a writer is -- Proust, say, or James Joyce -- the fact that so many willing and intelligent readers find them difficult, even impenetrable, is surely a mark, albeit in pencil, against them.

Ask a hundred readers to name the three greatest living writers and you will get a hundred different lists. If you want a thousand different lists, ask a thousand different readers. Who we happen to put on our own list depends on our individual taste and on whose books we have happened to read and enjoy. It also depends on which of the above quotations makes the most sense to us. Are you someone, like the character in Lara Vapnyar's novel, who assumes that if you don't understand a book, it must be pretty good? Or, like Susan Hill, do you believe the best writers are those who can make themselves understood, even when writing about difficult things?

Strange as it seems, some people do fall into that first group. Many college professors, book critics and various intellectuals, real or imagined, seem to feel this way. They favor books that only they and a few others can really appreciate, whether they actually understand these books or not.

My own list of the three best writers today, always subject to change, includes Ann Patchett, Donna Tartt and Jess Walter. In each of the past four years, the best novel I have read has been by one of these authors. An honorable mention list would include William Boyd, Larry Watson and Anne Tyler. I don't know about Boyd and Watson, but each of the others has had novels on the best-seller lists. In the view of some, that alone would disqualify these writers from being among the elite. If ordinary people read their books, they must not be very good.

Yet such writers as Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, Thomas Hardy and Anthony Trollope, all studied in college literature classes, were best-selling authors in their day. They satisfied the masses, while still giving scholars much to probe and dissect. I believe the same is true of the contemporary authors I mentioned. I am in the midst of Art and the Accidental in Anne Tyler by Joseph C. Voelker, a literature professor who studied Tyler's early novels. Some of Patchett's work, especially State of Wonder and Bel Canto, has received scholarly study. I don't know about the others, but I suspect they would lend themselves to serious study if anyone dared to do so.

The best works of literature offer something different for different readers. Those who just want a good story will find it in Tartt, Patchett and Walter as in Dickens, Twain and Hardy. Those who want deeper meaning will find that, as well.

Those words above from Susan Hill come near the end of her discussion of novelist V.S. Naipaul. She says of him, "He is a complex thinker, a magnificent prose writer, a painter on a broad canvas, able to portray not just a place but a continent and a philosophy, a history and a civilization. Yet he is always clear, always readable, deep but never obscure, which surely adds to the measure of his achievement."

Deep but never obscure. That sounds to me like a great definition of a great writer.

Lara Vapnyar, Still Here

Susan Hill, Howards End Is on the Landing

Strange as it seems, some people do fall into that first group. Many college professors, book critics and various intellectuals, real or imagined, seem to feel this way. They favor books that only they and a few others can really appreciate, whether they actually understand these books or not.

|

| Donna Tartt |

|

| Ann Patchett |

|

| Jess Walter |

The best works of literature offer something different for different readers. Those who just want a good story will find it in Tartt, Patchett and Walter as in Dickens, Twain and Hardy. Those who want deeper meaning will find that, as well.

Those words above from Susan Hill come near the end of her discussion of novelist V.S. Naipaul. She says of him, "He is a complex thinker, a magnificent prose writer, a painter on a broad canvas, able to portray not just a place but a continent and a philosophy, a history and a civilization. Yet he is always clear, always readable, deep but never obscure, which surely adds to the measure of his achievement."

Deep but never obscure. That sounds to me like a great definition of a great writer.

Friday, September 9, 2016

Unlikely writers of westerns

Two weeks from today in Columbus, Mary Doria Russell will receive the Ohioana Award for Epitaph, her novel about the gunfight at O.K. Corral. Her previous novel, also highly regarded, was Doc, about the life of Doc Holliday. Several years ago, also in Columbus, I happened to be in the audience when Russell mentioned she was working on a book about Doc Holliday. The author of such novels as The Sparrow and A Thread of Grace certainly didn't seem like someone who would write a western.

When we think of fiction about the Old West, we probably think of people like Zane Gray, Louis L'Amour, Max Brand, Ralph Compton or, a personal favorite, Richard S. Wheeler. Yet it occurs to me that many of the most significant western novels have been written by outsiders, writers like Mary Doria Russell who did not specialize in western novels yet happened to write one that was very, very good.

Robert Lewis Taylor, author of The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters, was a New Yorker writer who, among other books, wrote biographies of W.C. Fields and Winston Churchill.

Owen Wister wrote just one book about the West, but that one book was a classic, The Virginian.

Charles Portis wrote a number of novels, but none of the others was anything like True Grit.

Thomas Berger built a long career writing contemporary novels, yet his most notable work remains Little Big Man. Late in his career he tried to reclaim the magic with The Return of Little Big Man.

Brian Garfield is best remembered as a the author of the thriller Death Wish and its sequel Death Sentence, yet he wrote a number of westerns early in his career using various pseudonyms. Later he wrote the big western Wild Times, a novel I am currently rereading, under his own name.

Jane Smiley, like Mary Doria Russell, is hardly someone you would expect to write a western, yet her

1998 novel The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton is a gem.

Even Larry McMurtry was not known as western writer until he won the Pulitzer Prize with Lonesome Dove. Since then he has written a number of other tales of the Old West, although contemporary fiction remains his first love.

Most bookstores have small sections devoted to western novels, but to locate some of the best books in that genre you may have to look in the general fiction area under such names as Thomas Berger, Larry McMurtry and Mary Doria Russell.

When we think of fiction about the Old West, we probably think of people like Zane Gray, Louis L'Amour, Max Brand, Ralph Compton or, a personal favorite, Richard S. Wheeler. Yet it occurs to me that many of the most significant western novels have been written by outsiders, writers like Mary Doria Russell who did not specialize in western novels yet happened to write one that was very, very good.

Robert Lewis Taylor, author of The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters, was a New Yorker writer who, among other books, wrote biographies of W.C. Fields and Winston Churchill.

Owen Wister wrote just one book about the West, but that one book was a classic, The Virginian.

Charles Portis wrote a number of novels, but none of the others was anything like True Grit.

Thomas Berger built a long career writing contemporary novels, yet his most notable work remains Little Big Man. Late in his career he tried to reclaim the magic with The Return of Little Big Man.

Brian Garfield is best remembered as a the author of the thriller Death Wish and its sequel Death Sentence, yet he wrote a number of westerns early in his career using various pseudonyms. Later he wrote the big western Wild Times, a novel I am currently rereading, under his own name.

Jane Smiley, like Mary Doria Russell, is hardly someone you would expect to write a western, yet her

1998 novel The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton is a gem.

Even Larry McMurtry was not known as western writer until he won the Pulitzer Prize with Lonesome Dove. Since then he has written a number of other tales of the Old West, although contemporary fiction remains his first love.

Most bookstores have small sections devoted to western novels, but to locate some of the best books in that genre you may have to look in the general fiction area under such names as Thomas Berger, Larry McMurtry and Mary Doria Russell.

Wednesday, September 7, 2016

Hope for newspapers

Perhaps there is still hope for print journalism after all.

I entered the journalism business in the mid-Sixties when newspapers were all but begging for reporters. As a J-school senior at Ohio University, I never had to send letters to newspapers inquiring about a job. They sent letters to me, and from all over the country. After Watergate in the early Seventies, newspapers entered their glory days when newspapers didn't just report news -- they made news with their investigative journalism.

By the turn of the century, however, cutbacks were in full swing. Newspapers were eliminating staff members, pages from their product, the news and features that had once been on those pages and, in many cases, even their own presses. It became more efficient to hire some other newspaper to print their editions in another city and ship them back for distribution.

I recall telling a colleague about a big national story that would be in that day's paper. Her reply: "I'll have to watch that on TV tonight." Yes, even those who worked for newspapers had begun to get their news from television, and then from the Internet. Younger people in particular paid little attention to newspapers.

By the time I retired in 2010, I felt I was getting out just in time, before my own job was eliminated. Today that newspaper that once filled a large two-story downtown building could be operated out of a storefront.

So why is there still hope for newspapers? I find it in, yes, a newspaper story about a college newspaper, The Collegian at Ashland University. The Collegian dropped its print edition last December in favor of updating its website. The staff assumed they were just riding the wave into the digital future. Then, a few months later, they conducted a survey and discovered to their surprise how many people, both on campus and in the community, missed having an actual newspaper they could hold their hands. Some people, they learned, didn't even know there was a digital edition of the newspaper, out of sight apparently being out of mind.

So now The Collegian has returned to Ashland University in print, even if only an abbreviated biweekly edition. It carries the key features from the digital edition, and perhaps most importantly, reminds everyone on campus that there is, in fact, a digital edition.

Print journalism may never return to the heyday of the 1970s, but the lesson of The Collegian suggests that even some of those of the digital generation may prefer reading their news on paper.

I entered the journalism business in the mid-Sixties when newspapers were all but begging for reporters. As a J-school senior at Ohio University, I never had to send letters to newspapers inquiring about a job. They sent letters to me, and from all over the country. After Watergate in the early Seventies, newspapers entered their glory days when newspapers didn't just report news -- they made news with their investigative journalism.

By the turn of the century, however, cutbacks were in full swing. Newspapers were eliminating staff members, pages from their product, the news and features that had once been on those pages and, in many cases, even their own presses. It became more efficient to hire some other newspaper to print their editions in another city and ship them back for distribution.

I recall telling a colleague about a big national story that would be in that day's paper. Her reply: "I'll have to watch that on TV tonight." Yes, even those who worked for newspapers had begun to get their news from television, and then from the Internet. Younger people in particular paid little attention to newspapers.

By the time I retired in 2010, I felt I was getting out just in time, before my own job was eliminated. Today that newspaper that once filled a large two-story downtown building could be operated out of a storefront.

So why is there still hope for newspapers? I find it in, yes, a newspaper story about a college newspaper, The Collegian at Ashland University. The Collegian dropped its print edition last December in favor of updating its website. The staff assumed they were just riding the wave into the digital future. Then, a few months later, they conducted a survey and discovered to their surprise how many people, both on campus and in the community, missed having an actual newspaper they could hold their hands. Some people, they learned, didn't even know there was a digital edition of the newspaper, out of sight apparently being out of mind.

So now The Collegian has returned to Ashland University in print, even if only an abbreviated biweekly edition. It carries the key features from the digital edition, and perhaps most importantly, reminds everyone on campus that there is, in fact, a digital edition.

Print journalism may never return to the heyday of the 1970s, but the lesson of The Collegian suggests that even some of those of the digital generation may prefer reading their news on paper.

Monday, September 5, 2016

Brief encounter

As surprised as I was by the amount due on a bill for a recent appointment with a doctor, just $8.32, I was even more surprised to notice that the bill described that appointment as an encounter. Is that what that was? An encounter?

The word encounter is vague enough to mean a variety of things, from making love to making war. Mostly, however, it suggests, as my dictionary phrases it, "a sudden or unexpected meeting," as when you encounter an old friend at the supermarket. What the word doesn't suggest is something you can be billed for, not even $8.32. If the doctor encountered me, didn't I also encounter him? So why is he the one sending the bill?

I can understand being billed for an examination or a consultation. But encounter sounds like I met that doctor at the supermarket and we just had a brief chat about those pains in my chest while fondling the produce.

Another thing that caught by eye on that bill was the phrase "sequestration adjustment." We usually think of sequester as what they call it when they seclude juries from outside contact in important, multi-day trials, but the word can also mean "to confiscate." What was confiscated here was 67 cents, and it was confiscated not from me but apparently from the doctor. I assume it means the same as what another medical bill calls "MANDATED FED., STATE REG." I don't know what that means either, but the phrasing is a little easier to comprehend than "sequestration adjustment."

The word encounter is vague enough to mean a variety of things, from making love to making war. Mostly, however, it suggests, as my dictionary phrases it, "a sudden or unexpected meeting," as when you encounter an old friend at the supermarket. What the word doesn't suggest is something you can be billed for, not even $8.32. If the doctor encountered me, didn't I also encounter him? So why is he the one sending the bill?

I can understand being billed for an examination or a consultation. But encounter sounds like I met that doctor at the supermarket and we just had a brief chat about those pains in my chest while fondling the produce.

Another thing that caught by eye on that bill was the phrase "sequestration adjustment." We usually think of sequester as what they call it when they seclude juries from outside contact in important, multi-day trials, but the word can also mean "to confiscate." What was confiscated here was 67 cents, and it was confiscated not from me but apparently from the doctor. I assume it means the same as what another medical bill calls "MANDATED FED., STATE REG." I don't know what that means either, but the phrasing is a little easier to comprehend than "sequestration adjustment."

Friday, September 2, 2016

Books to impress

He had spent a lot of time choosing the book to read in that bar. Something French? Sartre's Nausea? Gilles Deleuze's Cinema I? And no, this wasn't sickeningly pretentious. Vadik wasn't doing it to make an impression on other people. He did want to be seen as a charismatic tweeded intellectual, but it was more important to him to be seen as such in his own eyes.

On the whole a serious novel, Lara Vapnyar's Still Here nevertheless has its flashes of wit, as in the case of the woman who "had forgotten how unbearably boring chewing your food was unless you did it while watching TV." My favorite light moment, however, occurs in the passage quoted above where Vadik goes to great trouble to select just the right book to be seen with in public. No, it's not that he is pretentious, he tells himself; he simply wants to appear intellectual "in his own eyes."

Of course, he could accomplish the latter by simply reading Sartre in the privacy of his own room, rather than pretending to read it in public. But no, he wants to be seen by others, even complete strangers, reading or at least holding a high-brow book. The boost in self-confidence comes from the impression made on others. That's what will make him feel better about himself. It might also be a way to pick up women.

Many of us have been guilty of selecting books on the basis of the impression they will leave with others, assuming anyone even notices what book we have with us. Notice that Vadik takes his book to a bar. Most bars I have entered have been too dark to read in, let alone to make out the title of someone else's book.

The books we choose to impress will vary depending upon whom we wish to impress and why. A person may want to seen with the latest best seller. Another novel I am reading is set in the 1930s. Women aboard a liner heading toward Europe make a point to be seen reading Gone With the Wind on deck. Some books become best sellers, or remain best sellers, because they are books stylish people want to be seen with.

For people more like Vadik, who wish to be seen as intellectual whether they are really intellectual or not, some high-brow book will do nicely.

One problem with reading a book on an iPad, Kindle or whatever is that the title cannot be displayed prominently for all to see. Nor can they notice how thick it is. How can you impress anyone that way?

Lara Vapnyar, Still Here

Of course, he could accomplish the latter by simply reading Sartre in the privacy of his own room, rather than pretending to read it in public. But no, he wants to be seen by others, even complete strangers, reading or at least holding a high-brow book. The boost in self-confidence comes from the impression made on others. That's what will make him feel better about himself. It might also be a way to pick up women.

Many of us have been guilty of selecting books on the basis of the impression they will leave with others, assuming anyone even notices what book we have with us. Notice that Vadik takes his book to a bar. Most bars I have entered have been too dark to read in, let alone to make out the title of someone else's book.

The books we choose to impress will vary depending upon whom we wish to impress and why. A person may want to seen with the latest best seller. Another novel I am reading is set in the 1930s. Women aboard a liner heading toward Europe make a point to be seen reading Gone With the Wind on deck. Some books become best sellers, or remain best sellers, because they are books stylish people want to be seen with.

For people more like Vadik, who wish to be seen as intellectual whether they are really intellectual or not, some high-brow book will do nicely.

One problem with reading a book on an iPad, Kindle or whatever is that the title cannot be displayed prominently for all to see. Nor can they notice how thick it is. How can you impress anyone that way?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)