The notion that happiness can be found somewhere else is at least as old as the saying that the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence. It is why immigrants still flock to the United States, why pioneers went west and why retirees head south. But are some places really happier than other places? Eric Weiner, a self-confessed grump, seeks to find out in his 2009 book The Geography of Bliss.

Weiner's unscientific research takes him to 10 countries, including the Netherlands, the center of truly scientific research into happiness; Iceland, Switzerland, Bhutan and Thailand, where people really do appear to be happier than those in most places, if for very different reasons; Moldova, where unhappiness abounds; Great Britain, where a project was conducted to attempt to make one town, Slough, happier; and the United States, where people may think they are happier than they really are. He also traveled to Qatar, one of the wealthiest nations on earth per capita, to see if money really can buy happiness, and to India, which despite its great poverty, draws people seeking happiness.

People in different cultures, Weiner finds, view happiness differently. Trust plays a big role in whether one feels happy or not. "Trusting your neighbors is especially important," he writes. "Simply knowing them can make a real difference in your quality of life." Diversity, while considered among the greatest virtues in today's world, tends not to enhance happiness. Most people feel happier among others like themselves, he discovers.

He concludes, "Money matters, but less than we think and not in the way that we think. Family is important. So are friends. Envy is toxic. So is excessive thinking. Beaches are optional. Trust is not. Neither is gratitude." Notice that his summary, except for the mention of beaches, ignores geography.

Weiner writes with such wit and charm that you will feel happier, at least temporarily, just for reading his book.

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Wednesday, May 27, 2015

Despite discouragement

My father-in-law, who grew up in Paulding, Ohio, loved reading the novels of Zane Grey in his youth. Near the end of his life, after his vision failed him, his eldest daughter, my wife, read to him some of these stories, both the westerns and the hunting and fishing tales.

I don't recall ever reading even one of Grey's books, but I was interested in a brief article about him I found in an old issue of Smithsonian (December 2001). Several things in this biography intrigued me.

He was born, Pearl Zane Gray, in Zanesville, Ohio, in 1872.

An outstanding baseball player in college (University of Pennsylvania), he was among the first pitchers to master the curveball.

"Grey has been credited with establishing the shape of the 20th-century western novel," Jake Page writes in the article.

Among his 89 books was one western set in Australia.

More than 100 movies have been based on his stories, and he formed his own production company to make western movies.

He had a strong dislike for Tom Mix, the star of several Zane Grey movies, because Mix was a noisy neighbor on Santa Catalina Island.

Grey once sailed to Tahiti in his yacht.

Yet one fact about Zane Grey's life has stuck with me most over the past several days. His father, a dentist, did his best to discourage his son's passion for writing stories, going so far as to tear up an early story and give the boy a thrashing. Young Pearl Gray surrendered to his father and became a reluctant dentist himself. That is, until he was 33 and broke free to follow his own dream.

The same issue of Smithsonian contains an excerpt from a book by paleontologist Michael Novacek, Time Traveler: In Search of Dinosaurs and Ancient Fossils. Novacek recalls attending a Catholic school, where the nuns disciplined him for reading concealed science books in class.

I wonder how many children, especially gifted children, have had their passions discouraged by parents, teachers or friends, however well-meaning these parents, teachers and friends may have been. Many people graduate from high school or college without knowing what they want to do with their lives, but others find their passions very early in life. For some kids it's computers. For others it's art. For others, like Novacek, it's science or, like Grey, writing.

Not all such discouragement is necessarily a bad thing. Children, left to themselves, would probably devote all their time to only those activities that most interest them, to the neglect of other things that will help them develop into a healthy, more rounded adult. My mother was always trying to get me to go outside, away from the books I wanted to read and the stories I wanted to write. Yet today I don't really regret those hours spent playing and working outdoors.

In some cases, discouragement may even be beneficial. I caught a couple of minutes of a TV show this week about ice skater Tonya Harding. Tonya spoke of how her mother discouraged her and made her childhood extremely difficult. Her mother's version was that Tonya was the kind of child who responded to reverse psychology: Tell her she couldn't do something and she became determined to do it anyway.

Most people, like Grey and Novacek and even Tonya Harding, seem to manage eventually to do, or at least to attempt to do, what they wanted to do all along.

I don't recall ever reading even one of Grey's books, but I was interested in a brief article about him I found in an old issue of Smithsonian (December 2001). Several things in this biography intrigued me.

He was born, Pearl Zane Gray, in Zanesville, Ohio, in 1872.

An outstanding baseball player in college (University of Pennsylvania), he was among the first pitchers to master the curveball.

"Grey has been credited with establishing the shape of the 20th-century western novel," Jake Page writes in the article.

Among his 89 books was one western set in Australia.

More than 100 movies have been based on his stories, and he formed his own production company to make western movies.

He had a strong dislike for Tom Mix, the star of several Zane Grey movies, because Mix was a noisy neighbor on Santa Catalina Island.

Grey once sailed to Tahiti in his yacht.

Yet one fact about Zane Grey's life has stuck with me most over the past several days. His father, a dentist, did his best to discourage his son's passion for writing stories, going so far as to tear up an early story and give the boy a thrashing. Young Pearl Gray surrendered to his father and became a reluctant dentist himself. That is, until he was 33 and broke free to follow his own dream.

The same issue of Smithsonian contains an excerpt from a book by paleontologist Michael Novacek, Time Traveler: In Search of Dinosaurs and Ancient Fossils. Novacek recalls attending a Catholic school, where the nuns disciplined him for reading concealed science books in class.

I wonder how many children, especially gifted children, have had their passions discouraged by parents, teachers or friends, however well-meaning these parents, teachers and friends may have been. Many people graduate from high school or college without knowing what they want to do with their lives, but others find their passions very early in life. For some kids it's computers. For others it's art. For others, like Novacek, it's science or, like Grey, writing.

Not all such discouragement is necessarily a bad thing. Children, left to themselves, would probably devote all their time to only those activities that most interest them, to the neglect of other things that will help them develop into a healthy, more rounded adult. My mother was always trying to get me to go outside, away from the books I wanted to read and the stories I wanted to write. Yet today I don't really regret those hours spent playing and working outdoors.

In some cases, discouragement may even be beneficial. I caught a couple of minutes of a TV show this week about ice skater Tonya Harding. Tonya spoke of how her mother discouraged her and made her childhood extremely difficult. Her mother's version was that Tonya was the kind of child who responded to reverse psychology: Tell her she couldn't do something and she became determined to do it anyway.

Most people, like Grey and Novacek and even Tonya Harding, seem to manage eventually to do, or at least to attempt to do, what they wanted to do all along.

Monday, May 25, 2015

Reading habits

In my adult life I cannot remember a single time when I was reading fewer than fifteen books, though at certain points this figure has spiraled far higher.

I can relate to Joe Queenan on this one. I haven't always been this way. There was a time when I read just one, maybe two books at a time. Over the years that number has somehow multiplied until, when I did a rough tally last night, I numbered at least 20 books in progress. Some of these have been "in progress" for a number of years. The count is imprecise because there are unfinished books throughout the house, as well as in both of our cars and in our Florida condo. Some books have been untouched for so long I'm sure I have forgotten them. I'm not sure whether to classify some books as unfinished or just abandoned.

"Like any addiction," writes Queenan, "the habit of ceaselessly starting new books provides me with immense pleasure." Yes, opening a new book and reading those first few pages can be irresistible. Reading the last few pages can also bring intense pleasure. It's those vast middle sections of most books, when plots bog down and when nonfiction books get clogged with uninteresting detail, that are the problem. Of course, stretching the reading of a book out over several years doesn't help matters. Queenan says he can remember what he has read before, but I am not always that lucky.

Reading so many books at one time means it can take a long time to finish a book. Yet it can mean finishing several books at about the same time, sometimes as many as three in a single day. So the numbers add up, even though progress seems slow. I consider it a good reading day when I have read a portion of at least 10 different books.

Juggling so many books at one time allows me to enjoy more diversity in my reading than most readers can boast. I try to maintain a balance between fiction and nonfiction, although I tend to read the novels more quickly. I like to be reading at least one mystery or thriller and at least one more serious work of literature at any one time, and I always have at least one book of short stories in progress. Currently I'm reading three.

I also like to be reading a biography, something about history, something about science, something about language, something about religion and something about literature. I also like to be reading something, such as a book of quotations, that I can pick up to read for just a couple of minutes at a time, such as during television commercials.

"My reading habits are unusual, perhaps counterproductive," Queenan says. So are my own, but reading habits, like any habits, are not easily broken. That's assuming I even wanted to break them.

Joe Queenan, One for the Books

"Like any addiction," writes Queenan, "the habit of ceaselessly starting new books provides me with immense pleasure." Yes, opening a new book and reading those first few pages can be irresistible. Reading the last few pages can also bring intense pleasure. It's those vast middle sections of most books, when plots bog down and when nonfiction books get clogged with uninteresting detail, that are the problem. Of course, stretching the reading of a book out over several years doesn't help matters. Queenan says he can remember what he has read before, but I am not always that lucky.

Reading so many books at one time means it can take a long time to finish a book. Yet it can mean finishing several books at about the same time, sometimes as many as three in a single day. So the numbers add up, even though progress seems slow. I consider it a good reading day when I have read a portion of at least 10 different books.

Juggling so many books at one time allows me to enjoy more diversity in my reading than most readers can boast. I try to maintain a balance between fiction and nonfiction, although I tend to read the novels more quickly. I like to be reading at least one mystery or thriller and at least one more serious work of literature at any one time, and I always have at least one book of short stories in progress. Currently I'm reading three.

I also like to be reading a biography, something about history, something about science, something about language, something about religion and something about literature. I also like to be reading something, such as a book of quotations, that I can pick up to read for just a couple of minutes at a time, such as during television commercials.

"My reading habits are unusual, perhaps counterproductive," Queenan says. So are my own, but reading habits, like any habits, are not easily broken. That's assuming I even wanted to break them.

Friday, May 22, 2015

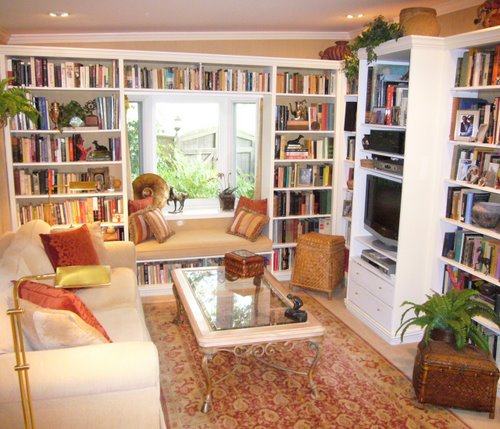

Why so many books?

"If anyone asks you if you've read all those books," he said, "it means you don't have enough books."

If you have more than a few books in your personal library, you have probably heard the question, "Have you read all these books?" Probably you have heard it more times than you can count. The question may be more revealing than the answer.

What it reveals, first, is that the questioner lacks imagination and may even be humor-challenged. It's a bit like asking a tall man, "How's the weather up there?" It may have been amusing once, but that once was a long, long time ago.

The second thing the question reveals about the person asking it is that this person lacks a passion for books, A Passion for Books being the title of the book from which the essay quoted above is found. Those who feel at all passionate about books never wonder why someone else shares that passion. They are more likely to be amazed that someone else does not.

As for the answer to that question, it being a yes or no question, there are just two basic answers. If the answer is yes, the owner of the library has read all those books, then maybe he or she really doesn't have enough books. Yet much can be said, especially when one has reached a certain point in life, for just rereading the books one has already enjoyed through a long lifetime. If a book is any good at all, reading it again and again is hardly a waste of time. Yet to the person asking the silly question, an affirmative answer may lead to yet another silly question, "If you've read them, why do you still have them?" To many people, including some who read a lot, a book is regarded as being much like facial tissue: When you're done with it, get rid of it.

Most likely, however, the person with a large library will not have read all those books. Some of those books may have been sitting on the shelf a long time waiting to be read. Some may never be read.

In truth, how this question is answered doesn't matter. It may not sound like it, but it is really a rhetorical question to which no answer is necessary. The person asking it is simply expressing amazement that anyone in his right mind would want to have so many books cluttering his home. Other people's passions can be difficult to comprehend.

Harold Rabinowitz, "They Don't Call It a Mania for Nothing"

What it reveals, first, is that the questioner lacks imagination and may even be humor-challenged. It's a bit like asking a tall man, "How's the weather up there?" It may have been amusing once, but that once was a long, long time ago.

The second thing the question reveals about the person asking it is that this person lacks a passion for books, A Passion for Books being the title of the book from which the essay quoted above is found. Those who feel at all passionate about books never wonder why someone else shares that passion. They are more likely to be amazed that someone else does not.

As for the answer to that question, it being a yes or no question, there are just two basic answers. If the answer is yes, the owner of the library has read all those books, then maybe he or she really doesn't have enough books. Yet much can be said, especially when one has reached a certain point in life, for just rereading the books one has already enjoyed through a long lifetime. If a book is any good at all, reading it again and again is hardly a waste of time. Yet to the person asking the silly question, an affirmative answer may lead to yet another silly question, "If you've read them, why do you still have them?" To many people, including some who read a lot, a book is regarded as being much like facial tissue: When you're done with it, get rid of it.

Most likely, however, the person with a large library will not have read all those books. Some of those books may have been sitting on the shelf a long time waiting to be read. Some may never be read.

In truth, how this question is answered doesn't matter. It may not sound like it, but it is really a rhetorical question to which no answer is necessary. The person asking it is simply expressing amazement that anyone in his right mind would want to have so many books cluttering his home. Other people's passions can be difficult to comprehend.

Wednesday, May 20, 2015

Learning other languages

Is someone who speaks three languages is a trilingualist and someone who speaks two languages is a bilingualist, what do you call someone who speaks just one language? The answer, according to the old joke, is an American.

Jokes are usually funny because they contain a grain of truth, and that is the case here. Most Americans, or at least most of the Americans I know, do speak just one language, English. Even if they studied another language in high school, that doesn't mean they can actually speak that language. I studied Latin in high school, which may give me a slight edge when I see Romance languages like Spanish or French, but doesn't help at all when I hear them spoken.

Language training in the United States tends to start too late, after the point when children can learn languages easily, and end too soon, before students can actually become comfortable with the second language.

Americans love to travel to other countries, but when they do they count on encountering people who speak good English. I enjoyed my visits to both the Netherlands and France a decade ago, but my fondest memories are of Amsterdam, not Paris. I'm sure that's because almost every Dutch person I met could speak good English, while relatively few French people could.

English has become virtually a universal language, taught in schools throughout the world. So maybe learning other languages isn't really that important. I've managed to do OK speaking just English. Still I wish I could converse with waiters and cab drivers in Paris or Montreal. I wish I knew what all those Spanish-speaking people I encounter in Florida are talking about. I wish I could travel to Germany or Japan and find my way around.

Schools already have too many government mandates. Still I'd like to see American schools, both public and private, encouraged to do a better job teaching languages. Such training shouldn't wait until high school. It should begin in the first grade, or better yet kindergarten, or even better yet, pre-school. Simply exposing young children to adults, or even other children, speaking another language on a daily basis would help teach that language. Children can learn languages with relative ease. If that training is re-enforced through the years they could one day become bilingual, or even trilingual, Americans.

Language training in the United States tends to start too late, after the point when children can learn languages easily, and end too soon, before students can actually become comfortable with the second language.

Americans love to travel to other countries, but when they do they count on encountering people who speak good English. I enjoyed my visits to both the Netherlands and France a decade ago, but my fondest memories are of Amsterdam, not Paris. I'm sure that's because almost every Dutch person I met could speak good English, while relatively few French people could.

English has become virtually a universal language, taught in schools throughout the world. So maybe learning other languages isn't really that important. I've managed to do OK speaking just English. Still I wish I could converse with waiters and cab drivers in Paris or Montreal. I wish I knew what all those Spanish-speaking people I encounter in Florida are talking about. I wish I could travel to Germany or Japan and find my way around.

Schools already have too many government mandates. Still I'd like to see American schools, both public and private, encouraged to do a better job teaching languages. Such training shouldn't wait until high school. It should begin in the first grade, or better yet kindergarten, or even better yet, pre-school. Simply exposing young children to adults, or even other children, speaking another language on a daily basis would help teach that language. Children can learn languages with relative ease. If that training is re-enforced through the years they could one day become bilingual, or even trilingual, Americans.

Monday, May 18, 2015

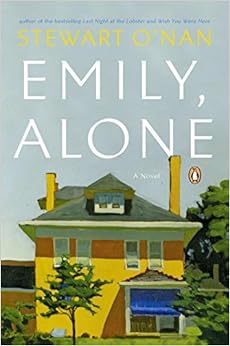

Trapped

Reading Stewart O'Nan's 2011 novel Emily, Alone I kept thinking of Mrs. Bridge, the terrific 1959 novel by Evan S. Connell Jr. Each novel is a character portrait of an upper-middle class woman who feels trapped in the life she has made for herself, or which has been made for her. Connell ends his novel with a classic scene that symbolizes both the kind of woman Mrs. Bridge is and the life she leads. Her car stalls as she is pulling out of her garage, and she cannot open any of the doors. Unable to get anyone's attention, for there is no one around, she simply sits there, her gloved hands folded in her lap, waiting to be rescued.

Emily Maxwell, the focus of O'Nan's story, is older than India Bridge, but is a similar kind of woman. Recently widowed by her beloved Henry, she struggles to stay in contact with her distant children and grandchildren and to, as much as possible, maintain the life she has been living for years, usually now in the company of her best friend, Arlene, a woman in similar circumstances.

Yet as the novel progresses in its brief, episodic chapters (again, much like Mrs. Bridge), we discover, as does Emily herself, she is living a lie. She listens to classical music on the radio all day every day, yet she dislikes most of what she hears. She attends The Nutcracker every year at Christmas, even though she hasn't enjoyed it in years. She doesn't even like spending so much time with Arlene.

As a girl, Emily was even more rebellious than her daughter, Margaret, ever was, yet where is that rebellion now? Like Mrs. Bridge caught in her own garage, Emily is trapped, not just by advancing age and declining health, but by a life that doesn't suit her anymore, if it ever did.

Emily Maxwell, the focus of O'Nan's story, is older than India Bridge, but is a similar kind of woman. Recently widowed by her beloved Henry, she struggles to stay in contact with her distant children and grandchildren and to, as much as possible, maintain the life she has been living for years, usually now in the company of her best friend, Arlene, a woman in similar circumstances.

Yet as the novel progresses in its brief, episodic chapters (again, much like Mrs. Bridge), we discover, as does Emily herself, she is living a lie. She listens to classical music on the radio all day every day, yet she dislikes most of what she hears. She attends The Nutcracker every year at Christmas, even though she hasn't enjoyed it in years. She doesn't even like spending so much time with Arlene.

As a girl, Emily was even more rebellious than her daughter, Margaret, ever was, yet where is that rebellion now? Like Mrs. Bridge caught in her own garage, Emily is trapped, not just by advancing age and declining health, but by a life that doesn't suit her anymore, if it ever did.

Friday, May 15, 2015

Foisting books on others

I hate having books rammed down my throat.

Joe Queenan goes on to say this may be why he never liked school. "I still cannot understand how one human being could ask another human being to read Look Homeward, Angel and then expect to remain on speaking terms."

I, on the other hand, loved school and always looked forward to discovering which books would be the assigned reading for each particular class. Maybe I didn't always enjoy reading these books, and maybe I just skimmed through a few of them, but today I at least have some familiarity with The Merchant of Venice, The Canterbury Tales, the poetry of T.S. Eliot, Lolita, Barchester Towers, The Heart of Midlothian and numerous other literary works because some high school teacher or college professor rammed them down my throat. I may have never dipped into any of them had they not been assigned reading. Today, all these years later, I have yet to read, or even opened, Look Homeward, Angel, and I regret that some instructor didn't assign it.

Yet I still agree with Queenan's basic point. I, too, hate having books rammed down my throat. Several weeks ago a woman simply handed me a copy of a biography of William A. Wheeler, vice president under Rutherford B. Hayes. She didn't ask me if I wanted to borrow the book. She simply gave it to me and began talking about something else. When Hayes learned that Wheeler had been nominated by the 1876 Republican National Convention to be his running mate, he is said to have asked, "Who is Wheeler?" Who is Wheeler, indeed. Unlike Hayes, I wasn't that interested in finding out. I did sample a few pages here and there in the book so I might have something intelligent to say when I returned it, but fortunately she again quickly turned to talking about something else, saving me the embarrassment of admitting I didn't actually read the book. I still consider her a friend.

I did at least return the book. Queenan says he keeps such books on the theory that "people who foist books upon other people don't really want them back." He writes, "Lending books to other people is merely a shrewd form of housecleaning." Even if that were true, why would either Queenan or I want other people's book cluttering up our homes. We already have our own books cluttering up our homes. Returning them, whether read or unread, as quickly as decently possible seems like the better way to go.

Gift books at least do not have to be returned, although you may feel obligated to read them at some point because someone was kind enough to give them to you. I still have a paperback copy of Tom Wolfe's The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby given as a Christmas present in the mid-'60s. I hope to get around to reading it someday.

I wrote book reviews for a newspaper for nearly 40 years, and even in retirement I receive, on average, one review book a month, which I write about in this blog, on the LibraryThing website and, rarely, for Amazon. Yet these books sent by publishers are not quite being "rammed down my throat." I have, with two exceptions during all those years, never been obligated to read or review any particular book, plus I get a some choice in which books I get from publishers. Even so, I have often felt I would rather be reading one of my own books according to my own schedule.

Joe Queenan, One for the Books

I, on the other hand, loved school and always looked forward to discovering which books would be the assigned reading for each particular class. Maybe I didn't always enjoy reading these books, and maybe I just skimmed through a few of them, but today I at least have some familiarity with The Merchant of Venice, The Canterbury Tales, the poetry of T.S. Eliot, Lolita, Barchester Towers, The Heart of Midlothian and numerous other literary works because some high school teacher or college professor rammed them down my throat. I may have never dipped into any of them had they not been assigned reading. Today, all these years later, I have yet to read, or even opened, Look Homeward, Angel, and I regret that some instructor didn't assign it.

Yet I still agree with Queenan's basic point. I, too, hate having books rammed down my throat. Several weeks ago a woman simply handed me a copy of a biography of William A. Wheeler, vice president under Rutherford B. Hayes. She didn't ask me if I wanted to borrow the book. She simply gave it to me and began talking about something else. When Hayes learned that Wheeler had been nominated by the 1876 Republican National Convention to be his running mate, he is said to have asked, "Who is Wheeler?" Who is Wheeler, indeed. Unlike Hayes, I wasn't that interested in finding out. I did sample a few pages here and there in the book so I might have something intelligent to say when I returned it, but fortunately she again quickly turned to talking about something else, saving me the embarrassment of admitting I didn't actually read the book. I still consider her a friend.

I did at least return the book. Queenan says he keeps such books on the theory that "people who foist books upon other people don't really want them back." He writes, "Lending books to other people is merely a shrewd form of housecleaning." Even if that were true, why would either Queenan or I want other people's book cluttering up our homes. We already have our own books cluttering up our homes. Returning them, whether read or unread, as quickly as decently possible seems like the better way to go.

Gift books at least do not have to be returned, although you may feel obligated to read them at some point because someone was kind enough to give them to you. I still have a paperback copy of Tom Wolfe's The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby given as a Christmas present in the mid-'60s. I hope to get around to reading it someday.

I wrote book reviews for a newspaper for nearly 40 years, and even in retirement I receive, on average, one review book a month, which I write about in this blog, on the LibraryThing website and, rarely, for Amazon. Yet these books sent by publishers are not quite being "rammed down my throat." I have, with two exceptions during all those years, never been obligated to read or review any particular book, plus I get a some choice in which books I get from publishers. Even so, I have often felt I would rather be reading one of my own books according to my own schedule.

Wednesday, May 13, 2015

Like Mama used to make

While eating my way home from Florida this week, I found myself thinking about such phrases as "home-made" and "made from scratch" so common in restaurants. What exactly do they mean anyway?

The term "home-made" makes me want to ask, "In whose home was this made?" Of course, I realize it has come to mean "made right here, not somewhere else and shipped in, then warmed in a microwave," or something like that. But even then what does it mean? Were the ingredients shipped in, perhaps already seasoned, sealed in packages, which were then opened, mixed and cooked, baked or deep fried by some high school dropout in the kitchen? Or did trained cooks or chefs start and end the process themselves, using fresh meat, fruits, vegetables and other ingredients?

The latter is suggested by the phrase "made from scratch." The phrase supposedly originated from the practice of scratching a line in the dirt to signify where runners in a race should begin. "Made from scratch" certainly implies the food in question began with the raw ingredients, not with any kind of mix. In Georgia we stopped at a Cracker Barrel, a restaurant chain fond of this phrase. Yet the "made from scratch" biscuits, dumplings or whatever seem to taste the same at Cracker Barrels everywhere. How is this possible if everything is made from scratch by scores of different cooks in scores of different restaurants? Of course, "made from scratch" does not necessarily mean "home-made." Could dough have been made from scratch somewhere else, then baked at the local restaurant?

The next day, stopping for lunch at Boone Tavern in Berea, Ky., I encountered the phrase "house made roast beef" on the menu? Now what might that mean? Did they butcher their own cattle or just roast their own beef or make their own sandwiches?

I don't mean to imply anything sinister about restaurants that employ such phrases. I love Cracker Barrel and Boone Tavern, which is why we stop there repeatedly. My point is simply that these phrases are used because a) they are suggestive and b) they are ambiguous. They suggest a meal like Mom used to make, or in the case of Cracker Barrel, like Grandma used to make. Their ambiguity, however prevents their being pinned down by lawyers, allowing a number of possible interpretations. How customers interpret the phrases may not necessarily be how restaurant owners interpret them.

The term "home-made" makes me want to ask, "In whose home was this made?" Of course, I realize it has come to mean "made right here, not somewhere else and shipped in, then warmed in a microwave," or something like that. But even then what does it mean? Were the ingredients shipped in, perhaps already seasoned, sealed in packages, which were then opened, mixed and cooked, baked or deep fried by some high school dropout in the kitchen? Or did trained cooks or chefs start and end the process themselves, using fresh meat, fruits, vegetables and other ingredients?

The latter is suggested by the phrase "made from scratch." The phrase supposedly originated from the practice of scratching a line in the dirt to signify where runners in a race should begin. "Made from scratch" certainly implies the food in question began with the raw ingredients, not with any kind of mix. In Georgia we stopped at a Cracker Barrel, a restaurant chain fond of this phrase. Yet the "made from scratch" biscuits, dumplings or whatever seem to taste the same at Cracker Barrels everywhere. How is this possible if everything is made from scratch by scores of different cooks in scores of different restaurants? Of course, "made from scratch" does not necessarily mean "home-made." Could dough have been made from scratch somewhere else, then baked at the local restaurant?

The next day, stopping for lunch at Boone Tavern in Berea, Ky., I encountered the phrase "house made roast beef" on the menu? Now what might that mean? Did they butcher their own cattle or just roast their own beef or make their own sandwiches?

I don't mean to imply anything sinister about restaurants that employ such phrases. I love Cracker Barrel and Boone Tavern, which is why we stop there repeatedly. My point is simply that these phrases are used because a) they are suggestive and b) they are ambiguous. They suggest a meal like Mom used to make, or in the case of Cracker Barrel, like Grandma used to make. Their ambiguity, however prevents their being pinned down by lawyers, allowing a number of possible interpretations. How customers interpret the phrases may not necessarily be how restaurant owners interpret them.

Thursday, May 7, 2015

Pitter-patter

In The Language Instinct, Steven Pinker wonders why we say ping-pong and pitter-patter rather than pong-ping and patter-pitter. Why see-saw and hee-haw and not saw-see and haw-hee? You could ask the same question about shilly-shally, ding-dong, clickety-clack, riff-raff, flim-flam, chit-chat, sing-song, spic and span and a number of other expressions.

Fortunately Pinker answers his own question, "The answer is that the vowels for which the tongue is high and in the front always come before the vowels for which the tongue is low and in the back."

Pinker goes further. We tend to place "words that connote me-here-now" in front of words that suggest someone else or somewhere else. Thus we say this and that, not that and this; now and then, not then and now; friend or foe, not foe or friend. He observes that Harvard students speak of the Harvard-Yale game, while Yale students call it the Yale-Harvard game.

I long ago noticed at wedding receptions that you can tell from the gift tag which side a wedding gift is from. At Bob and Sally's wedding, Bob's friends and family will write "Bob and Sally" on their gifts to the couple, while Sally's friends and family will write "Sally and Bob."

All this has made me wonder about partnerships. Do any rules apply in how the names are ordered? In law firms, I imagine the senior partner generally goes first. But what about comedy teams like Abbott and Costello, Burns and Allen, Rowen and Martin, and Martin and Lewis? In these instances, the straight man gets top billing, but what about Laurel and Hardy, Bob and Ray, Stiller and Meara, and Nichols and May?

And then there are those famous musical partnerships like Gilbert and Sullivan, Simon and Garfunkel, or Rodgers and Hammerstein. I think it sounds better to us when the shorter name is listed first, and in most show-business teams that seems to be the case. It's Bert and Ernie, after, all, not Ernie and Bert. Yet Rodgers and Hart sounded just as good to us as Rodgers and Hammerstein.

Fortunately Pinker answers his own question, "The answer is that the vowels for which the tongue is high and in the front always come before the vowels for which the tongue is low and in the back."

Pinker goes further. We tend to place "words that connote me-here-now" in front of words that suggest someone else or somewhere else. Thus we say this and that, not that and this; now and then, not then and now; friend or foe, not foe or friend. He observes that Harvard students speak of the Harvard-Yale game, while Yale students call it the Yale-Harvard game.

I long ago noticed at wedding receptions that you can tell from the gift tag which side a wedding gift is from. At Bob and Sally's wedding, Bob's friends and family will write "Bob and Sally" on their gifts to the couple, while Sally's friends and family will write "Sally and Bob."

All this has made me wonder about partnerships. Do any rules apply in how the names are ordered? In law firms, I imagine the senior partner generally goes first. But what about comedy teams like Abbott and Costello, Burns and Allen, Rowen and Martin, and Martin and Lewis? In these instances, the straight man gets top billing, but what about Laurel and Hardy, Bob and Ray, Stiller and Meara, and Nichols and May?

And then there are those famous musical partnerships like Gilbert and Sullivan, Simon and Garfunkel, or Rodgers and Hammerstein. I think it sounds better to us when the shorter name is listed first, and in most show-business teams that seems to be the case. It's Bert and Ernie, after, all, not Ernie and Bert. Yet Rodgers and Hart sounded just as good to us as Rodgers and Hammerstein.

Wednesday, May 6, 2015

The priorities of novelists

Literature made an abrupt change of direction about 100 years ago. Compare, say, Thomas Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1892) with James Joyce's Ulysses (1922). In the span of just 30 years (and you could use other examples to narrow the span further), the understanding of what constituted great literature changed dramatically. Writers like Hardy, Charles Dickens and Anthony Trollope gave way to writers like Joyce, Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner. Why?

What happened to the novel at about the time of the First World War was happening to other art forms, as well. Poetry no longer had to rhyme. Paintings no longer had to look like anything. The old rules no longer applied to novels either.

Thomas C. Foster analyses this change in his book How to Read Novels Like a Professor. He suggests that novelists' priorities changed from the 19th century to the 20th. In the 19th century, writers sought first to win an emotional response from their readers and after that, in order, an intellectual response and an aesthetic response. Early in the 20th century this hierarchy reversed itself. Writers sought first an aesthetic response, then an intellectual response and an emotional response.

Nineteenth century writers weren't interested in creating art. They were trying to make a living. People were more likely to buy books, or the publications in which novels were serialized, when they could be emotionally involved in the lives of the characters. Writers like Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner and those who followed in their footsteps did not have nearly as many readers because they didn't write stories that were as emotionally accessible. That's why so many of them have, like Faulkner, moonlighted as Hollywood screenwriters or, like most literary writers today, taught creative writing courses in colleges to supplement their incomes.

It is probably still too soon to predict what the priorities of 21st century novelists will be. Will aesthetics continue to be valued above all else, or will there be another change of direction? The ideal, it seems to me, would be a balance between the readers' emotional, aesthetic and intellectual responses. When I think of the two 21st century novels I most admire so far, State of Wonder by Ann Patchett and The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt, I think that perfect balance has been very nearly achieved. Readers respond emotionally to these stories, which have both been best sellers, yet they respond intellectually and aesthetically, as well. Both novels contain enough ambiguity for literature professors to argue about for years, yet enough clarity to give satisfaction to ordinary readers. They are smart, they are beautifully written and they can bring a tear to the reader's eye. Sounds like literary perfection to me.

What happened to the novel at about the time of the First World War was happening to other art forms, as well. Poetry no longer had to rhyme. Paintings no longer had to look like anything. The old rules no longer applied to novels either.

Thomas C. Foster analyses this change in his book How to Read Novels Like a Professor. He suggests that novelists' priorities changed from the 19th century to the 20th. In the 19th century, writers sought first to win an emotional response from their readers and after that, in order, an intellectual response and an aesthetic response. Early in the 20th century this hierarchy reversed itself. Writers sought first an aesthetic response, then an intellectual response and an emotional response.

Nineteenth century writers weren't interested in creating art. They were trying to make a living. People were more likely to buy books, or the publications in which novels were serialized, when they could be emotionally involved in the lives of the characters. Writers like Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner and those who followed in their footsteps did not have nearly as many readers because they didn't write stories that were as emotionally accessible. That's why so many of them have, like Faulkner, moonlighted as Hollywood screenwriters or, like most literary writers today, taught creative writing courses in colleges to supplement their incomes.

It is probably still too soon to predict what the priorities of 21st century novelists will be. Will aesthetics continue to be valued above all else, or will there be another change of direction? The ideal, it seems to me, would be a balance between the readers' emotional, aesthetic and intellectual responses. When I think of the two 21st century novels I most admire so far, State of Wonder by Ann Patchett and The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt, I think that perfect balance has been very nearly achieved. Readers respond emotionally to these stories, which have both been best sellers, yet they respond intellectually and aesthetically, as well. Both novels contain enough ambiguity for literature professors to argue about for years, yet enough clarity to give satisfaction to ordinary readers. They are smart, they are beautifully written and they can bring a tear to the reader's eye. Sounds like literary perfection to me.

Monday, May 4, 2015

'Rear Window' on a train

Turning spectators into participants is one of the key tricks used by writers of thrillers. The audience, whether those reading a book or watching a movie, is made to feel as if they, too, could easily be drawn into something dangerous and exciting.

The classic example of this may be Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window, in which a man with broken leg and a pair of binoculars thinks his neighbor may have murdered his wife. Laura Lippman did something similar a few years ago with her short novel The Girl in the Green Raincoat in which a pregnant woman confined to her own home observes a woman wearing a green raincoat walk her dog each day. Then one day she sees the dog, but not the woman. Thus begins an investigation that ultimately brings a killer to her door.

A similar idea powers the biggest bestseller of the year so far, The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins. Rachel is a recently divorced, alcoholic young woman who has lost her job because of her drinking yet still pretends to be working by taking the train to London each day. As the trains slows down through the town where she once lived with her husband, now married to another woman, Anna, she observe their lives in the same house along the tracks where she was once so happy. She also observes nearby another house where, in her imagination, the perfect couple lives. She thinks of them as Jess and Jason, but their real names are Megan and Scott. And then one night, a night in which Rachel has gotten off the train there and drunkedly tried to contact her ex-husband, Megan disappears. Rachel thinks she may have seen something that may help solve the mystery, but because of her alcoholism, nobody believes her.

This is a cleverly constructed tale that appropriately keeps the suspense building. The novel has three narrators, Rachel, Megan and Anna. Unfortunately, each narrator tells her story in the same way, in present tense and with events broken down into morning and evening, like diary entries. Shouldn't different women tell their stories a little differently?

The classic example of this may be Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window, in which a man with broken leg and a pair of binoculars thinks his neighbor may have murdered his wife. Laura Lippman did something similar a few years ago with her short novel The Girl in the Green Raincoat in which a pregnant woman confined to her own home observes a woman wearing a green raincoat walk her dog each day. Then one day she sees the dog, but not the woman. Thus begins an investigation that ultimately brings a killer to her door.

A similar idea powers the biggest bestseller of the year so far, The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins. Rachel is a recently divorced, alcoholic young woman who has lost her job because of her drinking yet still pretends to be working by taking the train to London each day. As the trains slows down through the town where she once lived with her husband, now married to another woman, Anna, she observe their lives in the same house along the tracks where she was once so happy. She also observes nearby another house where, in her imagination, the perfect couple lives. She thinks of them as Jess and Jason, but their real names are Megan and Scott. And then one night, a night in which Rachel has gotten off the train there and drunkedly tried to contact her ex-husband, Megan disappears. Rachel thinks she may have seen something that may help solve the mystery, but because of her alcoholism, nobody believes her.

This is a cleverly constructed tale that appropriately keeps the suspense building. The novel has three narrators, Rachel, Megan and Anna. Unfortunately, each narrator tells her story in the same way, in present tense and with events broken down into morning and evening, like diary entries. Shouldn't different women tell their stories a little differently?

Friday, May 1, 2015

What do you call your sandwich?

I crave meatball sandwiches the way most people crave pizza. In fact, whenever I find myself in a pizza restaurant, I am most likely to order their meatball sandwich. The problem is, what should I call it? Most likely it is not listed as a meatball sandwich on the menu.

Most often such a sandwich is called a submarine, or simply a sub, yet it is termed something different in different parts of the country. In the Tampa Bay Area of Florida, where I am living for at least a few more days, it can be termed something different at different restaurants on the same street. This is probably because the area has residents who came from all over the country, and in fact from all over the world.

At Sage's, a little Italian restaurant in a small shopping center in Largo, they serve the best meatball sandwich I have ever tasted. It has a perfect combination of tasty meatballs, cheese and marinara sauce on a toasted bun that practically melts in your mouth. They call it a grinder, a term most common in New England. Some meatball sandwiches tend to fall apart easily. Theirs doesn't.

Nearby at Widow Brown's, they call their sandwich a hoagie. That's a term most common in Pennsylvania.

Most chain restaurants, such as Subway, Checkers and Firehouse Subs, call these sandwiches subs.

At Cristino's, a pizza place in Clearwater where my wife and I ate lunch a week ago, they serve a delicious meatball panini. West Shore Pizza, a local chain, lists several paninis on their menu, but for whatever reason, their excellent, but messy, meatball sandwich is called simply a meatball sandwich.

There are other terms for these sandwiches, among them heros, bombers, blimps and poor boys. Whatever they're called, I usually like them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)