Sebastian Faulks does P.G. Wodehouse no favors in Jeeves and the Weddings Bells. Intended as an homage to Wodehouse, the first Jeeves and Wooster novel since Wodehouse's last, Aunts Aren't Gentlemen (or The Cat-Nappers), in 1974, seems more like an insult. It lacks the ridiculously complicated plot Wodehouse was known for. More seriously, it lacks the wit.

Sometimes Faulks finds a word or a phrase that sounds authentic, as when he writes "Jeeves shimmied in with the tea tray," but rarely a paragraph or even a complete sentence. As for his chapters, they are too long and never seem to end with any incentive to begin the next one. Jeeves and Wooster novels were never dull, until now.

The early premise of the story is actually quite good. Circumstances oddly call for Jeeves, the manservant, to pretend to be an English lord, while poor Bertie Wooster must play his servant, a wonderful changing of roles that, unfortunately, Faulks never manages to milk for all of its potential humor. The plot, such as it is, involves Bertie trying to aid one of his chums in winning the love of his life and, of course, making a mess of it. Leave it to Jeeves to sort things out in the end, although the resolution seems like something Wodehouse would have never concocted had he written a hundred Jeeves and Wooster novels.

As I've written before, Faulks did a nice job when he paid a similar homage to Ian Fleming in his James Bond novel Devil May Care. His latest tribute novel fails to deliver. But perhaps this is really an homage to Wodehouse after all. It demonstrates that not just anyone, not even a writer as gifted as Sebastian Faulks, can do what he did.

Friday, November 28, 2014

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

Short book about a long silence

There's not much to A Fifty-Year Silence: Love, War and a Ruined House in France, as its young author, Miranda Richmond Mouillot, concedes with this summary on the very last page: "Armand and Anna fell in love, bought a house and never spoke again." Her 263-page book details her efforts to discover why Armand and Anna, her maternal grandparents, never spoke again.

There is a bit more to the story. Armand and Anna, both Jews, survived World War II in France, although other family members did not. They saw little of each other during the war. Afterward they married, bought that house and lived together long enough to have a daughter. Then Armand became a translator at the Nuremberg Trials, where he learned firsthand what the Germans did to the Jews. After that, silence. Armand stayed in France. Anna moved to the United States, where years later Miranda was born. Why her grandparents never spoke, yet in some odd way still seemed to love one another, weighed on her mind while she was growing up. Eventually she found that ruined house, spent time with her grandfather and began to piece together the story that neither grandparent wanted to talk about.

Because this story really doesn't amount to much, Mouillot fills out her book with details of her own life, including her romance with and eventual marriage to a Frenchman. She's a fine writer. Not everyone could make so much out of so little and still make it worth reading.

There is a bit more to the story. Armand and Anna, both Jews, survived World War II in France, although other family members did not. They saw little of each other during the war. Afterward they married, bought that house and lived together long enough to have a daughter. Then Armand became a translator at the Nuremberg Trials, where he learned firsthand what the Germans did to the Jews. After that, silence. Armand stayed in France. Anna moved to the United States, where years later Miranda was born. Why her grandparents never spoke, yet in some odd way still seemed to love one another, weighed on her mind while she was growing up. Eventually she found that ruined house, spent time with her grandfather and began to piece together the story that neither grandparent wanted to talk about.

Because this story really doesn't amount to much, Mouillot fills out her book with details of her own life, including her romance with and eventual marriage to a Frenchman. She's a fine writer. Not everyone could make so much out of so little and still make it worth reading.

Friday, November 21, 2014

A revolution at the movies

As in the case with most Academy Awards ceremonies, there was less symbolism to be extracted from the evening than morning-after analysts might have imagined, and even that applied only to the Academy's taste in movies, not to the country's.

The above quotation, found near the end of Pictures at a Revolution, a fascinating 2008 book about the five movies nominated for best picture in 1968, seems like an odd thing for Mark Harris to say, given that his entire book focuses on the symbolism of those five movies and the 1968 Academy Awards. His thesis is that what he calls New Hollywood began to take over from Old Hollywood that year. All five movies nominated -- In the Heat of the Night, The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner and Doctor Doolittle -- were American-made, following a long period of British dominance at awards ceremonies. Younger, liberal, independent film makers, greatly influenced by European directors, began to replace older, conservative studio heads.

The ceremony in 1968, which was delayed by the death of Martin Luther King, reflected the struggle of the two camps, according to Harris. The Graduate and Bonnie and Clyde very much represented New Hollywood, while Doctor Doolittle, the only one of the five films to never break even, represented Old Hollywood. In the Heat of the Night, which won the award for best picture that year, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, were mostly Old Hollywood, but they both starred Sidney Poitier and both dealt with race relations, a timely topic even if the latter film was considered out of date by the time of its release.

Harris goes into exhaustive detail about the making of all five of those movies. Much of his information may be gathered from other sources, yet much of it is also based on his interviews with those involved in the productions. Among the tidbits he shares:

-- French directors Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard both considered directing Bonnie and Clyde. Instead Arthur Penn made the movie and got a nomination for his efforts. It may be a good thing Godard didn't take the job because he wanted to make the movie, set in Texas and surrounding states, in New Jersey in January.

-- Among actresses considered for the part of Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate were Doris Day, Jeanne Moreau, Patricia Neal and Ava Gardner. Anne Bancroft ultimately got the part. And the Simon and Garfunkel song Here's to You Mrs. Robinson was originally written to mention Mrs. Roosevelt.

-- Spencer Tracy's monologue at the end of Guess Who's Coming to Dinner took six days to shoot. Tracy was so ill at at the time he could work just a few hours each day. He died before the movie was released.

--Bosley Crowther, the longtime New York Times movie critic, lost his job because he panned Bonnie and Clyde again and again and again. He loved Cleopatra. Meanwhile, Pauline Kael got her job as film critic at The New Yorker because of an article she wrote praising Bonnie and Clyde.

Oliver!, made in Great Britain, won the Academy Award for best picture the following year, but it was the last British film to win until 1982 (Chariots of Fire). New Hollywood had taken over.

Mark Harris, Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood

The ceremony in 1968, which was delayed by the death of Martin Luther King, reflected the struggle of the two camps, according to Harris. The Graduate and Bonnie and Clyde very much represented New Hollywood, while Doctor Doolittle, the only one of the five films to never break even, represented Old Hollywood. In the Heat of the Night, which won the award for best picture that year, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, were mostly Old Hollywood, but they both starred Sidney Poitier and both dealt with race relations, a timely topic even if the latter film was considered out of date by the time of its release.

Harris goes into exhaustive detail about the making of all five of those movies. Much of his information may be gathered from other sources, yet much of it is also based on his interviews with those involved in the productions. Among the tidbits he shares:

-- French directors Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard both considered directing Bonnie and Clyde. Instead Arthur Penn made the movie and got a nomination for his efforts. It may be a good thing Godard didn't take the job because he wanted to make the movie, set in Texas and surrounding states, in New Jersey in January.

-- Among actresses considered for the part of Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate were Doris Day, Jeanne Moreau, Patricia Neal and Ava Gardner. Anne Bancroft ultimately got the part. And the Simon and Garfunkel song Here's to You Mrs. Robinson was originally written to mention Mrs. Roosevelt.

-- Spencer Tracy's monologue at the end of Guess Who's Coming to Dinner took six days to shoot. Tracy was so ill at at the time he could work just a few hours each day. He died before the movie was released.

--Bosley Crowther, the longtime New York Times movie critic, lost his job because he panned Bonnie and Clyde again and again and again. He loved Cleopatra. Meanwhile, Pauline Kael got her job as film critic at The New Yorker because of an article she wrote praising Bonnie and Clyde.

Oliver!, made in Great Britain, won the Academy Award for best picture the following year, but it was the last British film to win until 1982 (Chariots of Fire). New Hollywood had taken over.

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Naming the states

That so many place names in the United States, especially the names of states and rivers, were derived from indigenous American languages, rather than European languages, seems surprising. Sure we have state names like Rhodes Island, Virginia and Pennsylvania with obvious European roots, yet so many others were taken from Indian words, however corrupted those words may have been in the process.

My own state, Ohio, got its name from an Iroquois word meaning "good river." Michigan comes from a Chippewa word meaning "great water." Massachusetts comes from an Algonquian word, the meaning of which remains unclear although "great hill" is often mentioned. Connecticut got its name from Quinnehtukqut, which means "beside the long tidal river." Oregon may have gotten its name from an Indian name for a river, the Ouragon. Continuing the theme of naming states after Indian words referring to rivers, Mississippi comes from Misi-ziibi, meaning "great river." Idaho was supposedly named for a Shoshone word meaning "gem of the mountains," but this was later found to be a hoax. It was just a made-up word. Oklahoma comes from a Choctaw phrase meaning "red people."

And so it goes. Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Kansas, Alaska and Alabama are among other states whose names had Indian origins.

One of the oddest state name stories may be that of Wyoming, which Elizabeth Little says in Trip of the Tongue "comes from the same language that was spoken in and around what is now New York City." It was first used as a place name in eastern Pennsylvania, where there are towns named Wyoming, Wyomissing and Wyomissing Hills. At least a dozen other states have Wyoming as a place name, as do Ontario, Canada, and New South Wales, Australia. The popularity of the place name, Little writes, has to do with a poem by Thomas Campbell, which contains the line, "On Susquehanna's side, fair Wyoiming!" The word means either "at the big river flat" or "large prairie place," depending upon whom you believe.

|

| Ohio River |

And so it goes. Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Kansas, Alaska and Alabama are among other states whose names had Indian origins.

One of the oddest state name stories may be that of Wyoming, which Elizabeth Little says in Trip of the Tongue "comes from the same language that was spoken in and around what is now New York City." It was first used as a place name in eastern Pennsylvania, where there are towns named Wyoming, Wyomissing and Wyomissing Hills. At least a dozen other states have Wyoming as a place name, as do Ontario, Canada, and New South Wales, Australia. The popularity of the place name, Little writes, has to do with a poem by Thomas Campbell, which contains the line, "On Susquehanna's side, fair Wyoiming!" The word means either "at the big river flat" or "large prairie place," depending upon whom you believe.

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

The remembered victim

It was the crime that people remembered, not the victim.

When I started reading Laura Lippman's 2010 novel I'd Know You Anywhere, I wondered how she was going to make a story -- and knowing Lippman, a riveting story -- when the crimes in question (the abduction and murder of a series of teenage girls) happened years before and the killer sits on death row awaiting his execution. I needn't have worried, for the author pulls it off beautifully, and without relying too heavily on flashbacks.

The key to Lippman's story is that one of Walter Bowman's victims survived. Elizabeth Lerner, now Eliza Benedict, is married and has two children of her own, including a troubled daughter about the same age as she was when she stumbled upon Walter burying one of his victims. He grabbed her and took her with him on his travels. Trying to survive, she cooperated in every way, even to the point of not attempting to escape when she had the chance and aiding in the abduction of another girl, Holly Tackett. Her testimony helped put Walter on death row, where he has been for the past 20 years. But now he has found her again and hopes he can manipulate her as did years before, this time to save his life.

Eliza, who had thought her role in Walter Bowman's murder spree had long been forgotten, finds herself not just pressured by Walter but also caught between two women with opposing agendas. Trudy Tackett, Holly's mother, still blames Eliza for living when her own daughter died, and she wants to make sure Eliza does nothing to keep Walter from his appointment with death. Meanwhile Barbara, a woman who devotes herself to helping violent convicts, pushes Eliza to go along with Walter's scheme. In an author's note at the end of the novel, Lippman writes, "I did my best to make sure that every point of the (death penalty) triangle -- for, against, confused -- was represented by a character who is recognizably human." That she does very well, and all three women are flesh-and-blood characters you can understand, whether you agree with them or not.

Laura Lippman, I'd Know You Anywhere

The key to Lippman's story is that one of Walter Bowman's victims survived. Elizabeth Lerner, now Eliza Benedict, is married and has two children of her own, including a troubled daughter about the same age as she was when she stumbled upon Walter burying one of his victims. He grabbed her and took her with him on his travels. Trying to survive, she cooperated in every way, even to the point of not attempting to escape when she had the chance and aiding in the abduction of another girl, Holly Tackett. Her testimony helped put Walter on death row, where he has been for the past 20 years. But now he has found her again and hopes he can manipulate her as did years before, this time to save his life.

Eliza, who had thought her role in Walter Bowman's murder spree had long been forgotten, finds herself not just pressured by Walter but also caught between two women with opposing agendas. Trudy Tackett, Holly's mother, still blames Eliza for living when her own daughter died, and she wants to make sure Eliza does nothing to keep Walter from his appointment with death. Meanwhile Barbara, a woman who devotes herself to helping violent convicts, pushes Eliza to go along with Walter's scheme. In an author's note at the end of the novel, Lippman writes, "I did my best to make sure that every point of the (death penalty) triangle -- for, against, confused -- was represented by a character who is recognizably human." That she does very well, and all three women are flesh-and-blood characters you can understand, whether you agree with them or not.

Monday, November 10, 2014

Good stories vs. true stories

Good stories trump true stories. What happens with gossip also happens, more often than we might think, with history and the nightly news. Stories are told not necessarily because they are true but simply because they make good stories, which often means they conform with a particular bias.

Elizabeth Little comments on this power of good stories as it applies to language in her enchanting book Trip of the Tongue. The city of Puyallup, Wash., not far from Tacoma, obviously got its name from the Puyalllup Indian tribe from that area, but what does the word actually mean? The popular explanation is that the word means "generous people," and it is easy to see why that story would be popular. You can imagine what the local Chamber of Commerce might be able to do with it.

Yet Little found with a bit of research that the word actually means "bend at the bottom" or perhaps "bottom of the bend," which nicely describes where the city of Puyallup is located along a river. In other words, Puyallup, Wash., means about the same thing as South Bend, Ind. It's just harder to spell and harder to say and, because it is not an English word, opens the door for a better story.

Another example cited by Little has to do with the Chinese word for crisis. For years I have heard speakers point out that this word also means opportunity, the lesson being that a crisis, viewed in the right way, can also be an opportunity for positive change. That's a wonderful story, but Little points out that it's just not true.

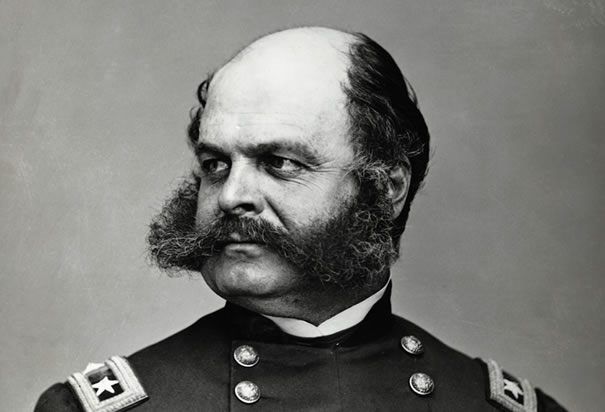

Little's comments made me think of a couple of common words that have both been attributed to Civil War generals: hooker and sideburns. The popular story is that the men serving under Major Gen. Joseph Hooker spent so much of their off-duty time in brothels that prostitutes came to be called hookers. Not true. The slang term has been in use at least since 1845, several years before the Civil War.

As for sideburns, the story has this word going back to Gen. Ambrose Burnside, known for the prominent whiskers on the side of his head. Happily, this story turns out to be true, showing that sometimes, at least, a good story can also be the true story.

Elizabeth Little comments on this power of good stories as it applies to language in her enchanting book Trip of the Tongue. The city of Puyallup, Wash., not far from Tacoma, obviously got its name from the Puyalllup Indian tribe from that area, but what does the word actually mean? The popular explanation is that the word means "generous people," and it is easy to see why that story would be popular. You can imagine what the local Chamber of Commerce might be able to do with it.

Yet Little found with a bit of research that the word actually means "bend at the bottom" or perhaps "bottom of the bend," which nicely describes where the city of Puyallup is located along a river. In other words, Puyallup, Wash., means about the same thing as South Bend, Ind. It's just harder to spell and harder to say and, because it is not an English word, opens the door for a better story.

Another example cited by Little has to do with the Chinese word for crisis. For years I have heard speakers point out that this word also means opportunity, the lesson being that a crisis, viewed in the right way, can also be an opportunity for positive change. That's a wonderful story, but Little points out that it's just not true.

|

| Ambrose Burnside |

As for sideburns, the story has this word going back to Gen. Ambrose Burnside, known for the prominent whiskers on the side of his head. Happily, this story turns out to be true, showing that sometimes, at least, a good story can also be the true story.

Friday, November 7, 2014

Who's in control?

I don't have a very clear idea of who the characters are until they start talking.

The notion that characters, in some sense, write their own stories is probably familiar to anyone who has listened to writers talk about their work. Usually there is at least one novelist at any gathering of writers who reflects on how characters tend to run away with the plot, taking it in new directions the author had never intended.

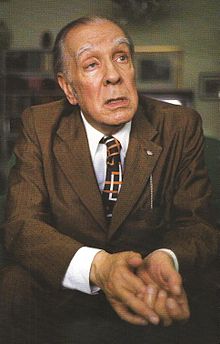

No less a writer than Jorge Luis Borges has said, "Many of the characters are fools and they are always playing tricks on me and treating me badly," suggesting that writing stories becomes something of a wrestling match in which the characters usually manage to pin the author.

I never realized this was a sensitive issue with some writers until I heard novelist Ann Patchett speak at Kenyon College a couple of weeks ago. She made it clear that, for better or worse, she writes her own stories. Her characters are her own creation and they speak only the words she puts into their mouths.

I have since found a couple of quotations from other writers who, more heatedly, say much the same thing.

John Cheever said, "The legend that characters run away from their authors -- taking up drugs, having sex operations, and becoming president -- implies that the writer is a fool with no knowledge or mastery of his craft. The idea of authors running around helplessly behind their cretinous inventions is contemptible."

Vladimir Nabokov put it this way, "The trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is a old as the quills. My characters are galley slaves."

During her Kenyon lecture, Patchett rebelled against another notion that someone or something other than the author might be responsible for the final product. She told the story, also told by novelist Elizabeth Gilbert, about the time the two of them, close friends, were discussing works in progress. Patchett was at that time working on State of Wonder, and Gilbert mentioned she had abandoned her own novel set in the Amazon. When Patchett asked what Gilbert's story was about, Gilbert outlined a plot eerily similar to Patchett's own, about a medical researcher in Minnesota, having an affair with her boss, who must travel to the Amazon.

Gilbert's explanation for this uncanny coincidence was that good ideas travel around the globe looking for receptive minds to bring them to fruition. The Amazon idea first landed on Gilbert, who ultimately rejected it. So the idea moved on to Patchett, who turned it into a great novel.

Patchett cannot explain how she and her friend both had the same idea, but she finds Gilbert's explanation silly. If two people have the same idea at the same time, perhaps it is "an incredibly banal idea," she thought at the time. That can sometimes be true. I recall that back in the early Seventies, two novels about fires in skyscrapers came out at about the same time. They were The Tower by Richard Martin Stern, which I reviewed at the time, and The Inferno, by Thomas M. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson. The two novels were later combined into one movie, The Towering Inferno, which won some Oscars.

In science and discovery it is not that unusual for ideas to strike different people at the same time, as in the case of the invention of the telephone and the theory of evolution. Even so, Patchett and Gilbert both conceiving the same plot for a novel does seem astounding. Perhaps suggesting that ideas travel through space looking for a home, like believing characters write the story themselves, is just a way of explaining the unexplainable.

Joan Didion

|

| Borges |

I never realized this was a sensitive issue with some writers until I heard novelist Ann Patchett speak at Kenyon College a couple of weeks ago. She made it clear that, for better or worse, she writes her own stories. Her characters are her own creation and they speak only the words she puts into their mouths.

I have since found a couple of quotations from other writers who, more heatedly, say much the same thing.

John Cheever said, "The legend that characters run away from their authors -- taking up drugs, having sex operations, and becoming president -- implies that the writer is a fool with no knowledge or mastery of his craft. The idea of authors running around helplessly behind their cretinous inventions is contemptible."

Vladimir Nabokov put it this way, "The trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is a old as the quills. My characters are galley slaves."

During her Kenyon lecture, Patchett rebelled against another notion that someone or something other than the author might be responsible for the final product. She told the story, also told by novelist Elizabeth Gilbert, about the time the two of them, close friends, were discussing works in progress. Patchett was at that time working on State of Wonder, and Gilbert mentioned she had abandoned her own novel set in the Amazon. When Patchett asked what Gilbert's story was about, Gilbert outlined a plot eerily similar to Patchett's own, about a medical researcher in Minnesota, having an affair with her boss, who must travel to the Amazon.

Gilbert's explanation for this uncanny coincidence was that good ideas travel around the globe looking for receptive minds to bring them to fruition. The Amazon idea first landed on Gilbert, who ultimately rejected it. So the idea moved on to Patchett, who turned it into a great novel.

Patchett cannot explain how she and her friend both had the same idea, but she finds Gilbert's explanation silly. If two people have the same idea at the same time, perhaps it is "an incredibly banal idea," she thought at the time. That can sometimes be true. I recall that back in the early Seventies, two novels about fires in skyscrapers came out at about the same time. They were The Tower by Richard Martin Stern, which I reviewed at the time, and The Inferno, by Thomas M. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson. The two novels were later combined into one movie, The Towering Inferno, which won some Oscars.

In science and discovery it is not that unusual for ideas to strike different people at the same time, as in the case of the invention of the telephone and the theory of evolution. Even so, Patchett and Gilbert both conceiving the same plot for a novel does seem astounding. Perhaps suggesting that ideas travel through space looking for a home, like believing characters write the story themselves, is just a way of explaining the unexplainable.

Wednesday, November 5, 2014

The ideal reader

Read as many of the great books as you can before the age of 22.

Last Friday in a post called "A skeptic's view of literature," I observed that for most of us, if we have read the great books or the classics at all, it was likely back when they were assigned reading for high school or college classes. We read them because we had to read them. After our formal education ends, if we read at all (and many college graduates never again open a book) it is much more likely to be something by Michener than Shakespeare or Tolstoy.

Yet two quotations, including the one from James Michener above, make me consider that there may be more to our reading of classics in our youth than just the reading required for English classes. A few days ago while reading an essay on despair by Joyce Carol Oates in the book Deadly Sins, I found this line, "Perhaps the ideal reader is an adolescent: restless, vulnerable, passionate, hungry to learn, skeptical and naive by

turns; with an unquestioned faith in the power of the imagination to change, if not life, one's comprehension of life."

Both Michener and Oates suggest those years before full adulthood may be the best time to read important literature, the best time to absorb it, to be influenced by it and inspired by it. More importantly, it may be the time in our lives when we are the most open to it, the most willing to read these books even when they are just recommended reading, not required reading.

Go into any large bookstore and you are likely to find a table of important books, both old and recent, that seems to be there primarily for adolescent readers. It is probably located in the young adult section of the store. These are not necessarily books that have been assigned in area schools. More likely they are just books adolescents, more than adults, will be drawn to.

I recall that it was in those years before graduation from college that I read so many books that were not necessarily great books but were nevertheless books I had heard about and wondered about, books I thought it might be valuable to read. These included such books as Lord of the Flies, 1984, Brave New World and most of the works of Steinbeck and Salinger. Perhaps it was then, more than any other time of my life, when I was, as Oates suggests, the ideal reader.

James Michener

Yet two quotations, including the one from James Michener above, make me consider that there may be more to our reading of classics in our youth than just the reading required for English classes. A few days ago while reading an essay on despair by Joyce Carol Oates in the book Deadly Sins, I found this line, "Perhaps the ideal reader is an adolescent: restless, vulnerable, passionate, hungry to learn, skeptical and naive by

turns; with an unquestioned faith in the power of the imagination to change, if not life, one's comprehension of life."

Both Michener and Oates suggest those years before full adulthood may be the best time to read important literature, the best time to absorb it, to be influenced by it and inspired by it. More importantly, it may be the time in our lives when we are the most open to it, the most willing to read these books even when they are just recommended reading, not required reading.

Go into any large bookstore and you are likely to find a table of important books, both old and recent, that seems to be there primarily for adolescent readers. It is probably located in the young adult section of the store. These are not necessarily books that have been assigned in area schools. More likely they are just books adolescents, more than adults, will be drawn to.

I recall that it was in those years before graduation from college that I read so many books that were not necessarily great books but were nevertheless books I had heard about and wondered about, books I thought it might be valuable to read. These included such books as Lord of the Flies, 1984, Brave New World and most of the works of Steinbeck and Salinger. Perhaps it was then, more than any other time of my life, when I was, as Oates suggests, the ideal reader.

Monday, November 3, 2014

Sin in the city

The first notable thing about Gary Krist's new book, Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans, may be its subtitle. The main title speaks of sin, yet between sex and murder lies jazz. Jazz?

Well, yes. It turns out that when reformers tried to clean up New Orleans early in the last century, their first target was not prostitution, gambling, booze, corruption or even gangland murders, but dancing. They didn't want women, at least not white women, in places where that new music, sometimes called jazz and sometimes jass, was being played by black musicians. Jazz, played by the likes of Jelly Roll Morton and a still very young Louis Armstrong, drew white audiences to clubs where black musicians played, and reformers found this as objectionable as anything else that was going on in Storyville.

An editorial in the Times-Picayune called "jass" a "form of musical vice" and said, "Its musical value is nil, and its possibilities of harm are great."

Storyville, named for Sidney Story, a New Orleans alderman, was a district of the city where vice was officially tolerated for a number of years. There was also a smaller area that became known as Black Storyville, but black musicians and a few black prostitutes were permitted in Storyville, just not black clientele. The area flourished and fortunes were made by those who owned the businesses, but Storyville was eventually crushed by those seeking reform. Prohibition, which became federal law at the close of World War I, put the final nail in Storyville's coffin. This did not end the sin in New Orleans, of course. It just went into hiding.

Most of the best jazz musicians fled New Orleans, finding more tolerant audiences in Chicago and elsewhere.

As for murder, there was plenty of that in New Orleans at the turn of the century, much of it associated with Italian mobsters. The most feared murderer at the time, the so-called Axeman, was never caught, and his identity remains a mystery to this day, although Krist suspects those killings, too, were mostly gang-related. A burly man broke into homes in the middle of the night and attacked people in their beds with an axe. Most, but not all, of the victims were Italians who owned small grocery stores.

Books about sin and the city have a lure, just like sin and cities themselves. I am thinking particularly of Karen Abbott's Sin and the Second City and Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City, both about Chicago. Krist himself wrote City of Scoundrels, also about Chicago. And just a couple of days ago I saw a similar book about Steubenville, Ohio. Empire of Sin may not be the best book of this kind, but it does make fascinating reading.

Well, yes. It turns out that when reformers tried to clean up New Orleans early in the last century, their first target was not prostitution, gambling, booze, corruption or even gangland murders, but dancing. They didn't want women, at least not white women, in places where that new music, sometimes called jazz and sometimes jass, was being played by black musicians. Jazz, played by the likes of Jelly Roll Morton and a still very young Louis Armstrong, drew white audiences to clubs where black musicians played, and reformers found this as objectionable as anything else that was going on in Storyville.

An editorial in the Times-Picayune called "jass" a "form of musical vice" and said, "Its musical value is nil, and its possibilities of harm are great."

Storyville, named for Sidney Story, a New Orleans alderman, was a district of the city where vice was officially tolerated for a number of years. There was also a smaller area that became known as Black Storyville, but black musicians and a few black prostitutes were permitted in Storyville, just not black clientele. The area flourished and fortunes were made by those who owned the businesses, but Storyville was eventually crushed by those seeking reform. Prohibition, which became federal law at the close of World War I, put the final nail in Storyville's coffin. This did not end the sin in New Orleans, of course. It just went into hiding.

Most of the best jazz musicians fled New Orleans, finding more tolerant audiences in Chicago and elsewhere.

As for murder, there was plenty of that in New Orleans at the turn of the century, much of it associated with Italian mobsters. The most feared murderer at the time, the so-called Axeman, was never caught, and his identity remains a mystery to this day, although Krist suspects those killings, too, were mostly gang-related. A burly man broke into homes in the middle of the night and attacked people in their beds with an axe. Most, but not all, of the victims were Italians who owned small grocery stores.

Books about sin and the city have a lure, just like sin and cities themselves. I am thinking particularly of Karen Abbott's Sin and the Second City and Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City, both about Chicago. Krist himself wrote City of Scoundrels, also about Chicago. And just a couple of days ago I saw a similar book about Steubenville, Ohio. Empire of Sin may not be the best book of this kind, but it does make fascinating reading.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)