Each year one novel seems to stand out in my mind. One year it was Ann Patchett's State of Wonder, for example. Another year it was The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt. I am not talking about the best novel published that year, as I don't read nearly enough new novels to make a judgment like that, but just the best novel read that year.

Singling out one novel is tough this year, not because there were no outstanding novels but because there were so many.

Reading Jess Walter's Beautiful Ruins was a beautiful experience, even if it didn't wow me quite as much as Citizen Vince did the year before. Another Ann Patchett novel, an early one called The Patron Saint of Liars, impressed me greatly, as did Richard B. Wright's Clara Callan and two novels that actually were published in 2016, Sweet Caress by William Boyd and As Good as Gone by Larry Watson. The Jack Matthews novel reviewed here a couple of days ago, The Gambler's Nephew, was an incredible pleasure to read.

Not quite as good as these six, but still very good were The Sleepwalker's Guide to Dancing by Mira Jacob, Yellow Blue Tibia by Adam Roberts, The Land of Decoration by Grace McCleen and two thrillers by Joe R. Landsdale, The Thicket and Edge of Dark Water.

So it was quite a year for reading, and that doesn't even count such nonfiction pleasures as Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City, Robert L. O'Connell's Fierce Patriot and Neal Thompson's A Curious Man.

The choice is hard, but I am going to make it anyway. Here are my top three novels of the year:

1. The Patron Saint of Liars

2. The Gambler's Nephew

3. As Good as Gone

Friday, December 30, 2016

Wednesday, December 28, 2016

Best for last

|

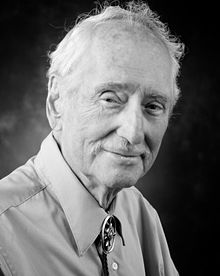

| Jack Matthews |

I took two creative writing classes taught by Matthews when I was a journalism student at Ohio University in the mid-1960s. He was about 40 then and had a book of short stories, Bitter Knowledge, and a book of poetry, An Almanac for Twilight, under his belt. Soon he was turning out novels like Hanger Stout, Awake!, Beyond the Bridge and The Charisma Campaigns, a favorite of mine. These were good novels, but not great, and despite a nomination for a National Book Award (for The Charisma Campaigns), he never achieved the literary big time. After 1983, although he continued to write both fiction and nonfiction books, these were published mostly by small presses and university presses.

Matthews died three years ago at the age of 88. His last novel, The Gambler's Nephew (Etruscan Press) was published in 2011, just two years before his death. So I didn't expect much when I started reading it a few days ago, yet I was blown away. This is an incredible novel that deserves more attention than it probably will ever receive.

The story begins in the 1850s in the Ohio River town of Brackenport, where a businessman named Nehemiah Dawes has such strong views about slavery and grave robbery that people tend to avoid him even if they agree with him. One day Dawes sees two men force a runaway slave into a boat to take him back to the other side of the river. Dawes has his gun with him and decides to back up his big talk by shooting one of the slavers. Instead he kills the young black man, yet doesn't receive as much as a stern talking to for his act. But when Dawes himself is found murdered, authorities are quick to hang a former employee, despite scant evidence of guilt.

Who is the protagonist in this novel? Matthews keeps us guessing. Until his death, it seems to be Nehemiah Dawes. Then the focus switches to his brother, to a young doctor and on and on to others, as main characters fade into the background. Much later we realize that the runaway slave, the "gambler's nephew" of the title, is the true protagonist, even though we never actually meet him in the story. Everything revolves around him, even when it doesn't seem to.

The novel, because of the voice of the mysterious narrator, seems lighter than it really is. We are tempted to read it with a smile, then may feel a trifle guilty when we realize where Matthews is taking us.

Whether or not The Gambler's Nephew is Jack Matthews's masterpiece, I will leave to the literary experts, if any of them bother to consider the question. But I will say that for a man in his 80s to produce a novel of such depth, power and grace is something amazing.

Monday, December 26, 2016

Quiz time

Each year at this time I like to ask myself a few questions, then answer them them using only the titles of books read during that year. The goal is to be as logical, as truthful and as humorous as possible, in that order of priority. So let's get on with the 2016 edition.

Describe yourself: A Curious Man

How do you feel? Still Here

Describe where you currently live: The Thicket

If you could go anywhere, where would you go? London

Your favorite form of transportation: Off the Grid

Your best friend is: Used and Rare

You and your friends are: Weirdos from Another Planet

What's the weather like where you are? Black Skies

What is the best advice you could give? Bring on the Girls!

Thought for the day: As Good as Gone

How would you like to die? The Good Goodbye

Your soul's present condition: The Way of the Heart

Most of these answers are logical, the main exception being Off the Grid as a form of transportation. The most blatant untruth is Black Skies to describe the weather. It is actually another sunny day here in Florida. And a couple of my answers make me smile, namely Weirdos from Another Planet, the title of a Calvin and Hobbes collection, and Bring on the Girls!, a P.G. Wodehouse book I plan to review in a few days. So I guess I deserve a passing grade.

Feel free to take this quiz yourself, using your own list of books read this year.

Describe yourself: A Curious Man

How do you feel? Still Here

Describe where you currently live: The Thicket

If you could go anywhere, where would you go? London

Your favorite form of transportation: Off the Grid

Your best friend is: Used and Rare

You and your friends are: Weirdos from Another Planet

What's the weather like where you are? Black Skies

What is the best advice you could give? Bring on the Girls!

Thought for the day: As Good as Gone

How would you like to die? The Good Goodbye

Your soul's present condition: The Way of the Heart

Most of these answers are logical, the main exception being Off the Grid as a form of transportation. The most blatant untruth is Black Skies to describe the weather. It is actually another sunny day here in Florida. And a couple of my answers make me smile, namely Weirdos from Another Planet, the title of a Calvin and Hobbes collection, and Bring on the Girls!, a P.G. Wodehouse book I plan to review in a few days. So I guess I deserve a passing grade.

Feel free to take this quiz yourself, using your own list of books read this year.

Friday, December 23, 2016

Creating traditions

The Tampa Bay Times has an article today about Festivus, the "holiday" created in a 1997 Seinfeld episode. Frank Costanza, George's father played by Jerry Stiller, announces, "At the Festivus dinner, you gather your family around, and you tell them all the ways they have disappointed you over the past year." It's sort of Thanksgiving in reverse, something people with a certain personality, or a certain sense of humor, might go for. And they do. Nearly 20 years later, Christopher Sparta tells us in his story, Festivus continues to be celebrated here and there. And today is Festivus.

Festivus works as an example of how popular culture shapes holiday celebrations. How we celebrate Christmas today, Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone write in Used and Rare, is heavily influenced by Charles Dickens and the incredible popularity of A Christmas Carol when it first appeared in 1843. "What before had been a one-day, quiet sort of holiday became an occasion for feasting and gifts, songs and games. Christmas cards, which had never been particularly popular before, suddenly became a fixture of the holiday," they write. "It was as though Charles Dickens had taught people how to rejoice and celebrate."

Since then popular culture has influenced the holiday in many ways. Another literary work, Clement Moore's "A Visit from St. Nicholas," written before the Dickens story, created lasting images of Santa Claus and his reindeer. A century later Gene Autry further shaped holiday celebrations with songs like Here Comes Santa Claus, Frosty the Snowman and Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Popular Christmas movies and A Charlie Brown Christmas have also had an impact.

Halloween, which has in recent decades developed into the second most popular holiday, is heavily influenced by popular culture. Just look at the favorite choices in costumes each year. Years ago the Detroit Lions made watching NFL football on television a part of the Thanksgiving tradition. Now there are three NFL games each Thanksgiving Day, and most of us consume too much football the way we consume too much turkey and pumpkin pie.

New traditions are being created all the time. Some will last, others won't.

Gloomy Festivus everyone!

Festivus works as an example of how popular culture shapes holiday celebrations. How we celebrate Christmas today, Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone write in Used and Rare, is heavily influenced by Charles Dickens and the incredible popularity of A Christmas Carol when it first appeared in 1843. "What before had been a one-day, quiet sort of holiday became an occasion for feasting and gifts, songs and games. Christmas cards, which had never been particularly popular before, suddenly became a fixture of the holiday," they write. "It was as though Charles Dickens had taught people how to rejoice and celebrate."

Since then popular culture has influenced the holiday in many ways. Another literary work, Clement Moore's "A Visit from St. Nicholas," written before the Dickens story, created lasting images of Santa Claus and his reindeer. A century later Gene Autry further shaped holiday celebrations with songs like Here Comes Santa Claus, Frosty the Snowman and Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Popular Christmas movies and A Charlie Brown Christmas have also had an impact.

Halloween, which has in recent decades developed into the second most popular holiday, is heavily influenced by popular culture. Just look at the favorite choices in costumes each year. Years ago the Detroit Lions made watching NFL football on television a part of the Thanksgiving tradition. Now there are three NFL games each Thanksgiving Day, and most of us consume too much football the way we consume too much turkey and pumpkin pie.

New traditions are being created all the time. Some will last, others won't.

Gloomy Festivus everyone!

Wednesday, December 21, 2016

Snobbish book dealers

This wasn't like the other book fairs we'd been to and not just because of the books. The dealers behaved differently. The usual banter was missing. They were less accessible and friendly. They even dressed better. Often, they seemed to size you up to guess at your bank balance before they would even answer a question about something they had on display.

What Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone are describing in the above excerpt from their book Used and Rare is their visit to the New York Antiquarian Book Fair in 1996. They had been to other book fairs, but this one had a different atmosphere. They felt that they, with their modest bank account, weren't really welcome.

I mentioned in my review of this book last week that they didn't feel welcome in some used bookshops either. In one they were denied access to the rare book room each time they asked. The first time they were told the woman in charge of the room wasn't available. On other visits when that woman was at her desk, apparently doing nothing, she had ready excuses as to why they could not enter. Once she said she was about to leave for lunch, although the Goldstones remained in the shop looking at less rare books and the woman never left her desk.

Caution by dealers in rare books makes sense, even if rudeness does not. Valuable rare books lose value the more they are handled. When I sold my first-edition copy of Sue Grafton's A Is for Alibi a few years ago, the dealer who bought it told me he would have paid much more if the book and especially the dust jacket had been in better condition. Why, he wondered, had I loaned it out to friends? But who knew back then what the book would be worth today?

When I attend the Florida Antiquarian Book Fair each March, I notice the most valuable books are kept behind glass so they won't be handled by everyone who comes along with an interest in seeing them but no interest in spending the thousands of dollars necessary to purchase them. People like me, in other words.

The snobbishness the Goldstones encountered may even be understandable up to a point. Relatively few people spend big money for rare books, and most of these people are just interested in certain books by certain authors. They probably would never ask to just look around the rare book room as the Goldstones did. Thus the woman guarding the door knew the couple were not serious buyers, so why allow them in?

Yet as the Goldstones wandered deeper and deeper into the book world, they found themselves spending more and more money on books. It might have been smarter if some of those dealers had treated them less like tourists and more like potential customers. And if they knew the couple would one day write a book about them, perhaps they would have.

Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone, Used and Rare

|

| Nancy Goldstone |

I mentioned in my review of this book last week that they didn't feel welcome in some used bookshops either. In one they were denied access to the rare book room each time they asked. The first time they were told the woman in charge of the room wasn't available. On other visits when that woman was at her desk, apparently doing nothing, she had ready excuses as to why they could not enter. Once she said she was about to leave for lunch, although the Goldstones remained in the shop looking at less rare books and the woman never left her desk.

Caution by dealers in rare books makes sense, even if rudeness does not. Valuable rare books lose value the more they are handled. When I sold my first-edition copy of Sue Grafton's A Is for Alibi a few years ago, the dealer who bought it told me he would have paid much more if the book and especially the dust jacket had been in better condition. Why, he wondered, had I loaned it out to friends? But who knew back then what the book would be worth today?

When I attend the Florida Antiquarian Book Fair each March, I notice the most valuable books are kept behind glass so they won't be handled by everyone who comes along with an interest in seeing them but no interest in spending the thousands of dollars necessary to purchase them. People like me, in other words.

The snobbishness the Goldstones encountered may even be understandable up to a point. Relatively few people spend big money for rare books, and most of these people are just interested in certain books by certain authors. They probably would never ask to just look around the rare book room as the Goldstones did. Thus the woman guarding the door knew the couple were not serious buyers, so why allow them in?

Yet as the Goldstones wandered deeper and deeper into the book world, they found themselves spending more and more money on books. It might have been smarter if some of those dealers had treated them less like tourists and more like potential customers. And if they knew the couple would one day write a book about them, perhaps they would have.

Monday, December 19, 2016

Skipping Christmas novels

There was A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, of course, if that can be called a novel, and a few years ago I read A Week in December by Sebastian Faulks, which although it may be set in December could just as easily have been set in June. Maybe there have been others, but none come to mind. Yet I could name any number of Christmas movies I have seen, many of them more than once. We watched Love Actually again just a few nights ago.

Do a web search and you can find countless Christmas novels, so somebody must read them. Or perhaps they buy them as Christmas presents. If so, they probably won't be opened until Christmas Day and even if started that day may not be finished until February. And who wants to read a Christmas novel in February?

I think that may partly explain why most of us don't view Christmas novels with the same fondness as Christmas movies. If we start watching a Christmas movie before Christmas, we will finish it before Christmas. Novels take longer. And, with the possible exceptions of A Christmas Carol or O. Henry's The Gift of the Magi, we probably don't want to read the same Christmas story every year or every other year, the way we may experience It's a Wonderful Life or A Christmas Story or Love Actually.

"I don't hate the holidays, but most holiday books leave me cold," Colette Bancroft, book editor for the Tampa Bay Times, wrote in Sunday's edition. I feel the same way. Some holiday books are sappy. Others just look sappy. Even if the stories are terrific, the books seem dated by the time the Christmas tree comes down.

Thursday, December 15, 2016

Spokesmen for their generations

"A book in its moment has romance. The book business is a romance business. Sometimes the dealer tries to build the romance, but in general, for the right books, it's already there."

Some writers continue to be read and admired long after their deaths, while most others simply disappear from view. No one reads them, no one writes about them and, after enough time passes, no one remembers them. But why is this so? I have always assumed it was just a matter of cream eventually rising to the top. Just as scholars are able to examine political figures more objectively after the passage of time, perhaps the same is true of literary figures. Thus some writers grow in stature as the years pass, while lesser ones fade from the scene. But maybe that is not the whole story.

George Minkoff, one of the rare book dealers Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone, the authors of Used and Rare, encounter on their travels, poses an interesting theory to them. He suggests the literary world, without necessarily even thinking about it, chooses a spokesman for particular times and places. "Spokesmen have been chosen for their generations," Minkoff said. "Steinbeck for the depression, Hemingway for the great expatriate era, Faulkner for the South after The Birth of the Nation... and that's who everybody reads ... and who everybody wants to buy."

The writer who best represents a particular niche in history is most likely to be remembered or at least gets the most attention, goes this theory. Thus, although people may still read Thomas Hardy, Anthony Trollope and a few others, it is Charles Dickens who most of us first think of as best representing Victorian England.

If all this is true, we are left to wonder which writer of those living today will be the spokesman for this generation. Which book, of all those published within the past few years, is the book of the moment? Which one has romance? Which will be remembered long after the others have been forgotten?

George Minkoff, bookseller, quoted in Used and Rare

Some writers continue to be read and admired long after their deaths, while most others simply disappear from view. No one reads them, no one writes about them and, after enough time passes, no one remembers them. But why is this so? I have always assumed it was just a matter of cream eventually rising to the top. Just as scholars are able to examine political figures more objectively after the passage of time, perhaps the same is true of literary figures. Thus some writers grow in stature as the years pass, while lesser ones fade from the scene. But maybe that is not the whole story.

George Minkoff, one of the rare book dealers Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone, the authors of Used and Rare, encounter on their travels, poses an interesting theory to them. He suggests the literary world, without necessarily even thinking about it, chooses a spokesman for particular times and places. "Spokesmen have been chosen for their generations," Minkoff said. "Steinbeck for the depression, Hemingway for the great expatriate era, Faulkner for the South after The Birth of the Nation... and that's who everybody reads ... and who everybody wants to buy."

The writer who best represents a particular niche in history is most likely to be remembered or at least gets the most attention, goes this theory. Thus, although people may still read Thomas Hardy, Anthony Trollope and a few others, it is Charles Dickens who most of us first think of as best representing Victorian England.

If all this is true, we are left to wonder which writer of those living today will be the spokesman for this generation. Which book, of all those published within the past few years, is the book of the moment? Which one has romance? Which will be remembered long after the others have been forgotten?

Wednesday, December 14, 2016

Adventures in the book world

There are books that tell readers how to go about collecting rare books, but Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone's Used and Rare: Travels in the Book World shows you how to do it. The disadvantage is that there is no index at the end to help one later find specific information, but the advantage is that you can follow along as two complete novices find their way into the somewhat exclusive world of book collectors.

How exclusive is it? The Goldstones tell us about about dealers who don't have signs on their doors, often because they operate their businesses out of their own homes, or who want to know how you found them, never mind that their numbers and addresses are in the phone book. The couple makes repeated visits to one bookshop and each time are denied access to the rare book room with one lame excuse or another. The authors name names, both those of the businesses and the people who work there. If names were changed to protect the guilty, we are not told.

The Goldstones convey information while at the same telling interesting, often humorous, stories about their travels from their Connecticut home to shops in surrounding states. They describe book auctions, conversations with dealers, both the helpful and unhelpful ones, and answer questions, like how does one tell if a book is really a first edition, that other beginning collectors are going to ask.

Unlike many collectors, the Goldstones are interested mainly in books they want to read or have read and want attractive copies on their shelves. They lack the resources to spend thousands of dollars on a single rare book, yet still want to build a collection that will be valuable to them. "The more we thought about it," they conclude, "the more we came back to our original view. You don't really need first editions at all. They are just affectations, excuses for dealers to run up the price on you, charge you a lot of money for something that doesn't read any better than any other edition."

As enjoyable as Used and Rare is, it can be annoying at times, as when these two people seem to think with a single mind. We find the sentence, "'We have this in paperback, but these stories are terrific,' one of us commented to the other." These writers have the ability to repeat entire conversations word for word, but they can't remember which of them made that statement? I don't mind that the Goldstones never argue, but do they always want to buy the same books and are they always willing to pay the same price? One gets the impression that one of these two people isn't really necessary. Or maybe hiring the babysitter wasn't really necessary. One of them could have just stayed home.

How exclusive is it? The Goldstones tell us about about dealers who don't have signs on their doors, often because they operate their businesses out of their own homes, or who want to know how you found them, never mind that their numbers and addresses are in the phone book. The couple makes repeated visits to one bookshop and each time are denied access to the rare book room with one lame excuse or another. The authors name names, both those of the businesses and the people who work there. If names were changed to protect the guilty, we are not told.

The Goldstones convey information while at the same telling interesting, often humorous, stories about their travels from their Connecticut home to shops in surrounding states. They describe book auctions, conversations with dealers, both the helpful and unhelpful ones, and answer questions, like how does one tell if a book is really a first edition, that other beginning collectors are going to ask.

Unlike many collectors, the Goldstones are interested mainly in books they want to read or have read and want attractive copies on their shelves. They lack the resources to spend thousands of dollars on a single rare book, yet still want to build a collection that will be valuable to them. "The more we thought about it," they conclude, "the more we came back to our original view. You don't really need first editions at all. They are just affectations, excuses for dealers to run up the price on you, charge you a lot of money for something that doesn't read any better than any other edition."

As enjoyable as Used and Rare is, it can be annoying at times, as when these two people seem to think with a single mind. We find the sentence, "'We have this in paperback, but these stories are terrific,' one of us commented to the other." These writers have the ability to repeat entire conversations word for word, but they can't remember which of them made that statement? I don't mind that the Goldstones never argue, but do they always want to buy the same books and are they always willing to pay the same price? One gets the impression that one of these two people isn't really necessary. Or maybe hiring the babysitter wasn't really necessary. One of them could have just stayed home.

Monday, December 12, 2016

Fame and food

On our first night in Daytona Beach, we stopped for what was for us a late dinner at Steve's Famous Diner along the beach. I had never heard of it before, not that there are not many famous people, places and things I have never heard about. Ever since I have been wondering about such questions as: Just how famous is Steve's Famous Diner? What is it famous for? (Could it be for the saltiness of the food?) How long has it been famous? Did it become famous before or after the restaurant was named?

On another vacation earlier this year in Gatlinburg, Tenn., a town that could be famous for the number of pancake houses on the major streets, we stopped at one where the sign proudly proclaimed their "famous pancakes." I had never heard of them either. The pancakes didn't taste any better to me than those served by Bob Evans, so I have no idea how these particular pancakes won fame.

Putting Google to work I find, farther down the Florida coast, Fireman Derek's World Famous Pies in Miami. Ever hear of them? Me neither. The Soup Cafe in South Orange, N.J., boasts "the world's most famous soups." Never heard of them. There seem to be a number of establishments that serve "famous chicken," "famous pizza" and so forth. Is fame, real or imagined, really the best way to sell food to hungry people? I liked Steve's Famous Diner for its location, decor and menu choices, even if the food itself was too salty. Its being famous did not impress me at all.

That which is truly famous does not need to advertise the fact. You never hear any references to "famous Lady Gaga" or "famous Brad Pitt" or "famous Hillary Clinton." Nor does KFC need to boast about "famous chicken" or Bob Evans about "famous pancakes." Fame is something that when you've got it, there's no need to brag about it.

On another vacation earlier this year in Gatlinburg, Tenn., a town that could be famous for the number of pancake houses on the major streets, we stopped at one where the sign proudly proclaimed their "famous pancakes." I had never heard of them either. The pancakes didn't taste any better to me than those served by Bob Evans, so I have no idea how these particular pancakes won fame.

Putting Google to work I find, farther down the Florida coast, Fireman Derek's World Famous Pies in Miami. Ever hear of them? Me neither. The Soup Cafe in South Orange, N.J., boasts "the world's most famous soups." Never heard of them. There seem to be a number of establishments that serve "famous chicken," "famous pizza" and so forth. Is fame, real or imagined, really the best way to sell food to hungry people? I liked Steve's Famous Diner for its location, decor and menu choices, even if the food itself was too salty. Its being famous did not impress me at all.

That which is truly famous does not need to advertise the fact. You never hear any references to "famous Lady Gaga" or "famous Brad Pitt" or "famous Hillary Clinton." Nor does KFC need to boast about "famous chicken" or Bob Evans about "famous pancakes." Fame is something that when you've got it, there's no need to brag about it.

Friday, December 9, 2016

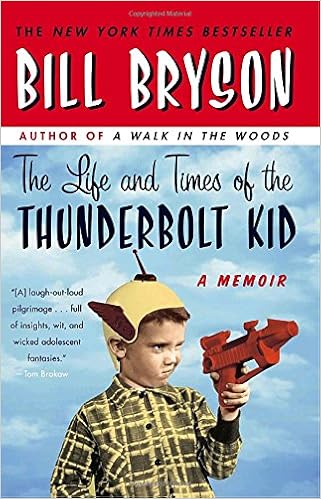

A great time to be a kid

In The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, Bill Bryson reminds those of us of a certain age what a privilege it was to grow up in the 1950s. Sure there was polio, the McCarthy hearings and the threat of nuclear annihilation, but those were things our parents worried about, not us kids. For children, it was a golden time. We were allowed, no encouraged, to wander around our neighborhoods most of the day -- my friend and I called it "exploring" -- and our parents never seemed to worry about us or even place limits on how far we could go or, as long as we didn't miss a meal, when we had to be back.

Bryson, a few years younger than me, spent his childhood in Des Moines, the son of one of the best baseball writers in America, never mind that Des Moines has never had a major league baseball team. Even so his father went to spring training every year and to the World Series every fall and won many writing awards. Bryson's mother, too, worked for the Des Moines Register, so if writing skill is something that can be inherited, which I doubt, we know where he got it from.

His memoir devotes attention to the toys of that era (who can forget electric football, Lincoln Logs and, my favorite, chemistry sets?), school, family vacations (like my own family, Bryson's didn't travel much, but even so we both made it to Disneyland somehow), early television, grandparents, the discovery of sex and other topics related to growing up.

Although he has never been known as a writer of fiction, Bryson strays close in this memoir, as when he tells of his adventures as his own superhero, the Thunderbolt Kid, or when he tells about a roller coaster "about four miles long, I believe, and some twelve thousand feet high." Exaggeration works in creating an amusing, sometimes outrageously funny, book.

"One of the great myths of life is that childhood passes quickly," Bryson writes. Indeed, time passes at glacier speed for children, if not for their parents, who like to tell each other how "they grow up so fast." I continue to marvel at how much I managed to pack into each day back in the 1950s, and it seems even more marvelous now at an age when if I can accomplish one thing in the morning and another thing in the afternoon, I think I have had a productive day. It was as if I, too, were the Thunderbolt Kid.

Bryson, a few years younger than me, spent his childhood in Des Moines, the son of one of the best baseball writers in America, never mind that Des Moines has never had a major league baseball team. Even so his father went to spring training every year and to the World Series every fall and won many writing awards. Bryson's mother, too, worked for the Des Moines Register, so if writing skill is something that can be inherited, which I doubt, we know where he got it from.

His memoir devotes attention to the toys of that era (who can forget electric football, Lincoln Logs and, my favorite, chemistry sets?), school, family vacations (like my own family, Bryson's didn't travel much, but even so we both made it to Disneyland somehow), early television, grandparents, the discovery of sex and other topics related to growing up.

Although he has never been known as a writer of fiction, Bryson strays close in this memoir, as when he tells of his adventures as his own superhero, the Thunderbolt Kid, or when he tells about a roller coaster "about four miles long, I believe, and some twelve thousand feet high." Exaggeration works in creating an amusing, sometimes outrageously funny, book.

"One of the great myths of life is that childhood passes quickly," Bryson writes. Indeed, time passes at glacier speed for children, if not for their parents, who like to tell each other how "they grow up so fast." I continue to marvel at how much I managed to pack into each day back in the 1950s, and it seems even more marvelous now at an age when if I can accomplish one thing in the morning and another thing in the afternoon, I think I have had a productive day. It was as if I, too, were the Thunderbolt Kid.

Wednesday, December 7, 2016

Is it time for lunch yet?

He commuted there every morning in a boat rowed by two oarsmen, had his dinner (what we would now call lunch) in a house on Sollers Point, and in the evening was rowed back to the nearby mainland ...

His mind was occupied with business matters, although he was fighting sleepiness from eating a substantial noontime dinner of pork chops, fried chicken, succotash, candied yams, stewed beets, green onions in vinegar, and hot buttered corn muffins.

I was sitting in a local restaurant about to start lunch one afternoon last week when I overheard the waitress say to the man at the next table, "Are you here for breakfast?"

That, plus the two lines above found in my recent reading has gotten me thinking about what we call the meals we eat. At one time people lucky enough to get three meals a day ate breakfast, dinner and supper. In rural communities in particular, the custom was to serve the biggest meal at noon, and that was called dinner. Michael Korda's biography of Robert E. Lee and the novel by Jack Matthews both describe terminology common in the middle of the 19th century. My rural 20th century parents called their noon meal dinner throughout their lives. When I went to school and later to work in the city, I got a lunch hour each day, and I began to think of the evening meal as dinner, not supper. This is not the case on Sundays and holidays, however, when my biggest meal usually comes in midday. Two weeks ago I ate Thanksgiving dinner at noon and had a light supper around 6 or 7.

Since my youth, terms for meals seem to have gotten more confusing in other ways. Take brunch, for example, a term popular with those who like to sleep in, especially on Sundays, or who want to skip breakfast but don't want to wait for lunch. In restaurants, however, brunch may be served until 2 p.m. or later, well after my usual lunch time.

Our words for our meals don't necessarily refer to the time of day, because that other man in the restaurant wanted breakfast at the same time I wanted lunch (and my father would have wanted dinner and somebody else might want brunch).

Nor do they necessarily refer to the kind of food being served. We associate eggs, bacon and pancakes with breakfast, but many of us like eggs, bacon and pancakes at other meals. I, in fact, am thinking about having pancakes, bacon and eggs today for lunch, even though I ate eggs and a biscuit for breakfast. We tend to associate home fries and hash browns with breakfast, french fries with lunch and baked or mashed potatoes with dinner, but there is plenty of variation on when people eat all kinds of potatoes. Some people like steak for breakfast, though when I have steak, unless it's in a sandwich, it had better be dinner.

Meanwhile people today work, sleep and eat at all hours. How can they keep straight which meal is breakfast, which is lunch and which is dinner? Here in Florida a lot of senior citizens are having dinner at around 4 in the afternoon, when some younger people are still having lunch (or breakfast). But is it even necessary that each meal have a name? Perhaps we will eventually get to the point where a meal is just meal and restaurants will serve you whatever you feel like whatever the time of day.

Michael Korda, Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee

Jack Matthews, The Gambler's Nephew

That, plus the two lines above found in my recent reading has gotten me thinking about what we call the meals we eat. At one time people lucky enough to get three meals a day ate breakfast, dinner and supper. In rural communities in particular, the custom was to serve the biggest meal at noon, and that was called dinner. Michael Korda's biography of Robert E. Lee and the novel by Jack Matthews both describe terminology common in the middle of the 19th century. My rural 20th century parents called their noon meal dinner throughout their lives. When I went to school and later to work in the city, I got a lunch hour each day, and I began to think of the evening meal as dinner, not supper. This is not the case on Sundays and holidays, however, when my biggest meal usually comes in midday. Two weeks ago I ate Thanksgiving dinner at noon and had a light supper around 6 or 7.

Since my youth, terms for meals seem to have gotten more confusing in other ways. Take brunch, for example, a term popular with those who like to sleep in, especially on Sundays, or who want to skip breakfast but don't want to wait for lunch. In restaurants, however, brunch may be served until 2 p.m. or later, well after my usual lunch time.

Our words for our meals don't necessarily refer to the time of day, because that other man in the restaurant wanted breakfast at the same time I wanted lunch (and my father would have wanted dinner and somebody else might want brunch).

Nor do they necessarily refer to the kind of food being served. We associate eggs, bacon and pancakes with breakfast, but many of us like eggs, bacon and pancakes at other meals. I, in fact, am thinking about having pancakes, bacon and eggs today for lunch, even though I ate eggs and a biscuit for breakfast. We tend to associate home fries and hash browns with breakfast, french fries with lunch and baked or mashed potatoes with dinner, but there is plenty of variation on when people eat all kinds of potatoes. Some people like steak for breakfast, though when I have steak, unless it's in a sandwich, it had better be dinner.

Meanwhile people today work, sleep and eat at all hours. How can they keep straight which meal is breakfast, which is lunch and which is dinner? Here in Florida a lot of senior citizens are having dinner at around 4 in the afternoon, when some younger people are still having lunch (or breakfast). But is it even necessary that each meal have a name? Perhaps we will eventually get to the point where a meal is just meal and restaurants will serve you whatever you feel like whatever the time of day.

Monday, December 5, 2016

Miracle worker

Judith McPherson, the 10-year-old narrator of Grace McCleen's impressive first novel The Land of Decoration, defines a miracle in an early chapter as "what you see when you stop thinking." Perhaps because she thinks too much, Judith begins to see herself as a miracle worker. At first her power seems a blessing, but it becomes more and more a curse because miracles, like wishes granted by genies, don't always work the way they are intended.

Her mother died after her birth, and Judith has been raised by her father, a simple laborer who is a part of a fundamentalist congregation with strict ideas about sin and punishment. Judith knows Father loved her mother, but she isn't so sure that he really loves her.

The introverted girl spends most of her time alone in her room, in which she creates what she calls the Land of Decoration, a phrase based on an Old Testament passage. She has made, in effect, her own little world made out of rubbish, complete with mountains, buildings, rivers and pipe-cleaner people. One day she covers her world with cotton snow, and the next day an early-season blizzard strikes her town. A couple of days later she does it again. From then on, anything she does in her Land of Decoration happens in the real world, even if not quite as she might have imagined it.

Much is going on Judith's life beyond the Land of Decoration. Her father decides to continue working even though most of his fellow workers go on strike. She is bullied at school, and when one of the bullies follows her home, her house becomes a target of vandalism by him and his friends. This drives her father, already under extreme pressure at work, into a panic, especially when the police seem incapable of stopping the nightly assaults on his property. When he builds a fence to protect the house, authorities come after him for his illegal fence.

And then there are her almost daily conversations with God, who seems more like a kooky uncle.

The trouble with stories like this is how to end them in a satisfactory way without everything being a dream or the product of a character's imagination. The usual solution is to obfuscate the conclusion so that readers haven't a clue as to what is going on. Until McCleen arrives at the dilemma point, her novel proves rich and wonderful. After that, well, I for one was left unsatisfied.

Her mother died after her birth, and Judith has been raised by her father, a simple laborer who is a part of a fundamentalist congregation with strict ideas about sin and punishment. Judith knows Father loved her mother, but she isn't so sure that he really loves her.

The introverted girl spends most of her time alone in her room, in which she creates what she calls the Land of Decoration, a phrase based on an Old Testament passage. She has made, in effect, her own little world made out of rubbish, complete with mountains, buildings, rivers and pipe-cleaner people. One day she covers her world with cotton snow, and the next day an early-season blizzard strikes her town. A couple of days later she does it again. From then on, anything she does in her Land of Decoration happens in the real world, even if not quite as she might have imagined it.

Much is going on Judith's life beyond the Land of Decoration. Her father decides to continue working even though most of his fellow workers go on strike. She is bullied at school, and when one of the bullies follows her home, her house becomes a target of vandalism by him and his friends. This drives her father, already under extreme pressure at work, into a panic, especially when the police seem incapable of stopping the nightly assaults on his property. When he builds a fence to protect the house, authorities come after him for his illegal fence.

And then there are her almost daily conversations with God, who seems more like a kooky uncle.

The trouble with stories like this is how to end them in a satisfactory way without everything being a dream or the product of a character's imagination. The usual solution is to obfuscate the conclusion so that readers haven't a clue as to what is going on. Until McCleen arrives at the dilemma point, her novel proves rich and wonderful. After that, well, I for one was left unsatisfied.

Friday, December 2, 2016

Books in boxes

It was wonderful unpacking a big box filled with books, even if we had mailed it to ourselves.

Opening almost any kind of package can provide a measure of excitement. This may even include taking items out of bags following a trip to the grocery store. For those of us who love books, nothing can quite match opening a box of books, even if, like Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone, we are the ones who placed the books in that box.

I ship books to myself every year following a winter in Florida. I reserve the limited shelf space in our Florida condo for books I have yet to read. Before returning to our much more spacious Ohio home, I place the books I've read over the winter into boxes and ship them home. These boxes await me at the post office upon my return. I may know what's in them, but even so I look forward to opening them and removing the books one by one.

A step up in the excitement level happens when ordering books from catalogs or through an Internet site, like Amazon. Here, too, I know what to expect, but I have yet to actually see these particular books or hold them in my hands. So simply opening the box, especially when it is a large box, can become the highlight of the day.

For nearly 40 years I reviewed books for a newspaper, and as incredible as it still seems to me, a variety of publishers actually sent me books on a regular basis. Some days my desk would be stacked with boxes of books, and rarely did I know what was inside these boxes. So I could experience something of the joy of a kid at Christmas almost every day. And as on Christmas morning, the contents of the package were often disappointing. Other times I felt like I had hit a jackpot.

Although retired from professional reviewing, I continue to receive usually one review copy a month through LibraryThing, so the excitement of receiving free books directly from publishers is not entirely a thing of the past.

Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone, Used and Rare

Opening almost any kind of package can provide a measure of excitement. This may even include taking items out of bags following a trip to the grocery store. For those of us who love books, nothing can quite match opening a box of books, even if, like Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone, we are the ones who placed the books in that box.

I ship books to myself every year following a winter in Florida. I reserve the limited shelf space in our Florida condo for books I have yet to read. Before returning to our much more spacious Ohio home, I place the books I've read over the winter into boxes and ship them home. These boxes await me at the post office upon my return. I may know what's in them, but even so I look forward to opening them and removing the books one by one.

A step up in the excitement level happens when ordering books from catalogs or through an Internet site, like Amazon. Here, too, I know what to expect, but I have yet to actually see these particular books or hold them in my hands. So simply opening the box, especially when it is a large box, can become the highlight of the day.

For nearly 40 years I reviewed books for a newspaper, and as incredible as it still seems to me, a variety of publishers actually sent me books on a regular basis. Some days my desk would be stacked with boxes of books, and rarely did I know what was inside these boxes. So I could experience something of the joy of a kid at Christmas almost every day. And as on Christmas morning, the contents of the package were often disappointing. Other times I felt like I had hit a jackpot.

Although retired from professional reviewing, I continue to receive usually one review copy a month through LibraryThing, so the excitement of receiving free books directly from publishers is not entirely a thing of the past.

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

The art of murder

|

| Thomas De Quincey |

It is another of De Quincey's writings, On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts (1827) that Morrell uses as a launchpad for his 2013 novel, the first in a series, Murder as a Fine Art. De Quincey wrote about the infamous Ratcliffe Highway killings of 1811. Morrell imagines that, decades later, the crimes by the Ratcliffe Highway killer are repeated, almost death for death, as if to rub them in De Quincey's face.

At first, De Quincey is himself considered a suspect in the new round of bloody murders. Soon, accompanied by his youngest daughter, Emily, he is assisting Detective Inspector Ryan and Constable Becker in trying to solve the crimes. Or perhaps they are assisting him, so sharp is his mind, at least when he has access to a steady supply of laudanum.

Morrell, a literature professor before he became a best-selling author of thrillers (beginning with First Blood), became a Thomas De Quincey scholar before beginning this series of novels, and it shows in the detail he provides about De Quincey and his times. Also, Morrell provides his readers with a short history lesson at the beginning of virtually every chapter, writing about the London police force, the popularity of laudanum as a pain reliever in De Quincey's day, the spread of cholera in London in the middle of the 19th century and other topics relating to his story.

Murder as a Fine Art may be a violent novel, especially in the initial chapter, but it is an unusually fine mystery, one that may inspire some of us to seek out some of Thomas De Quincey's work.

Monday, November 28, 2016

Celebrate some words

Let's celebrate some centennials today, not of individuals, places or events but of words.

It can be difficult to be certain exactly when words were coined. Often they are used in conversation long before somebody writes them down, but not until they are written down in books or other publications can later scholars assign dates to them. Sol Steinmetz, in his book There's a Word for It (2010), provides lists of words coined, or at least put into print for the first time, every year from 1900 to 2009. So let's look at the words that appeared first in 1916, 100 years ago.

When I see lists of words arranged by their date of origin, I find myself dividing them into three groups in my mind: those I would have thought to be older, those I would have thought to be newer and those that sound about right. So allow me to do that now.

1916 words that seem older

Ambivalent, counterattack (used as a verb), dagnab it, dealership, goof, Midwesterner, multimillion and pastrami.

1916 words that seem newer

Carcinogenic, cryptobiotic, dysfunction, ecotype, environmentalist, homo-erotic, hush-hush, penny-pincher, princessy, punchline, Realtor and sex drive.

1916 words that seem about right

World War I was well under way in 1916, and certain words and phrases from that year appear to have grown out of that war. These include blimp, jarhead, munitioneer, national service, over the top, R.O.T.C., steel helmet and trip-wire.

Actually there are several other words on Steinmetz's list that I don't know where to place on one of my own. These include cuckoo-land, economy size, excludable, low-maintenance, photofinishing, profiteer and well-scrubbed.

Some of the words from 1916 we might have done very well without, but others, especially such handy gems as ambivalent and punchline, are certainly worth celebrating.

It can be difficult to be certain exactly when words were coined. Often they are used in conversation long before somebody writes them down, but not until they are written down in books or other publications can later scholars assign dates to them. Sol Steinmetz, in his book There's a Word for It (2010), provides lists of words coined, or at least put into print for the first time, every year from 1900 to 2009. So let's look at the words that appeared first in 1916, 100 years ago.

When I see lists of words arranged by their date of origin, I find myself dividing them into three groups in my mind: those I would have thought to be older, those I would have thought to be newer and those that sound about right. So allow me to do that now.

1916 words that seem older

Ambivalent, counterattack (used as a verb), dagnab it, dealership, goof, Midwesterner, multimillion and pastrami.

1916 words that seem newer

Carcinogenic, cryptobiotic, dysfunction, ecotype, environmentalist, homo-erotic, hush-hush, penny-pincher, princessy, punchline, Realtor and sex drive.

1916 words that seem about right

World War I was well under way in 1916, and certain words and phrases from that year appear to have grown out of that war. These include blimp, jarhead, munitioneer, national service, over the top, R.O.T.C., steel helmet and trip-wire.

Actually there are several other words on Steinmetz's list that I don't know where to place on one of my own. These include cuckoo-land, economy size, excludable, low-maintenance, photofinishing, profiteer and well-scrubbed.

Some of the words from 1916 we might have done very well without, but others, especially such handy gems as ambivalent and punchline, are certainly worth celebrating.

Friday, November 25, 2016

Literary prizes for songwriters?

A few weeks ago I mentioned folksinger Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in connection with Paul Simon's denial that he himself is a poet. I didn't get into the question of whether literary prizes should be given to songwriters. Let's do that now.

A fellow LibraryThing member argued in a discussion group that Dylan's "not a literary figure, he's a songwriter and there are plenty of venues that celebrate excellence in music." That is a good point. Is there a hall of fame for poetry the way there is for rock and roll music and country music? Are the National Book Awards televised the way the Grammys and other music award presentations are? And are there as many categories so that one writer can win multiple awards and many writers can win at least one? (Of course, because there are so many categories of Grammy Awards, poets and other literary figures have sometimes won them. Grammy winners have included Maya Angelou, James Dickey, Carl Sandburg and Rod McKuen.)

Yet just because a poem is set to music does not mean that it is no longer a poem. There was a time when virtually every literate person read poetry. Today relatively few people do, but they do listen to it. And so most of our poets, like those who wrote the psalms in biblical times, set their poetry to music. I argued in my Nov. 2 post that Paul Simon is a poet. I could make a similar case for Leonard Cohen, who died recently, Dar Williams and many other singer-songwriters.

The quality of the poetry should not be judged on the basis of the music or the voice of the singer or the writer's celebrity. If you are going to give literary prizes to songwriters, it had better be because the words themselves and the strength of their imagery make them deserving. It would not do to start handing out literary prizes to celebrities in the music world at the expense of those who write quality books and poems in relative obscurity. But an occasional Nobel Prize for a Bob Dylan? I have no problem with that.

A fellow LibraryThing member argued in a discussion group that Dylan's "not a literary figure, he's a songwriter and there are plenty of venues that celebrate excellence in music." That is a good point. Is there a hall of fame for poetry the way there is for rock and roll music and country music? Are the National Book Awards televised the way the Grammys and other music award presentations are? And are there as many categories so that one writer can win multiple awards and many writers can win at least one? (Of course, because there are so many categories of Grammy Awards, poets and other literary figures have sometimes won them. Grammy winners have included Maya Angelou, James Dickey, Carl Sandburg and Rod McKuen.)

Yet just because a poem is set to music does not mean that it is no longer a poem. There was a time when virtually every literate person read poetry. Today relatively few people do, but they do listen to it. And so most of our poets, like those who wrote the psalms in biblical times, set their poetry to music. I argued in my Nov. 2 post that Paul Simon is a poet. I could make a similar case for Leonard Cohen, who died recently, Dar Williams and many other singer-songwriters.

The quality of the poetry should not be judged on the basis of the music or the voice of the singer or the writer's celebrity. If you are going to give literary prizes to songwriters, it had better be because the words themselves and the strength of their imagery make them deserving. It would not do to start handing out literary prizes to celebrities in the music world at the expense of those who write quality books and poems in relative obscurity. But an occasional Nobel Prize for a Bob Dylan? I have no problem with that.

Wednesday, November 23, 2016

A writer who reads

Larry McMurtry, a prolific writer who also happens to be a prolific reader, surprised me when he observed in one of his books that many writers don't read all that much. Visiting in authors' homes and looking over their shelves, he said he often sees few books other than those they have written themselves or that have been sent to them by publishers hoping for some kind words to use as a blurb. I had always assumed that reading, whether for research or inspiration, was a prerequisite for writing.

One writer, other than McMurtry, who does read a lot is Laura Lippman. I have commented on this in past posts. Her crime fiction has numerous literary references, and in her personal appearances she often mentions books she has read. So when I read Baltimore Blues, her first Tess Monaghan novel, I decided to make note of her literary references. There turned out to be more than I expected.

She places three quotations at the front of the novel. One is from H.L. Mencken, "Of all escape mechanisms, death is the most efficient." Another comes from a letter written by a Baltimore doctor. later published in an 1873 book. The third consists of lines from A.E. Housman's poem, Terence, This Is Stupid Stuff. That Housman poem comes up twice in the 324-page novel, and another Housman poem is mentioned as well.

During the course of her story, she mentions, usually through her characters, Thomas Hardy, James Thurber's Walter Mitty character, John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity and Mildred Pierce (Cain, in fact, pops up again and again in the novel), W.H. Auden, W.B. Yeats, Ernest Hemingway, John Milton, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, A.S. Byatt, Edgar Allan Poe and Don Quixote.

In addition, Tess works part-time in her aunt's used bookshop, and the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore is referred to as "a place of wonders to Tess."

All this is in a murder mystery that could be classified as light reading. Best of all, these many literary references contribute to the plot without getting in the way.

|

| Laura Lippman |

She places three quotations at the front of the novel. One is from H.L. Mencken, "Of all escape mechanisms, death is the most efficient." Another comes from a letter written by a Baltimore doctor. later published in an 1873 book. The third consists of lines from A.E. Housman's poem, Terence, This Is Stupid Stuff. That Housman poem comes up twice in the 324-page novel, and another Housman poem is mentioned as well.

| W.H. Auden |

In addition, Tess works part-time in her aunt's used bookshop, and the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore is referred to as "a place of wonders to Tess."

All this is in a murder mystery that could be classified as light reading. Best of all, these many literary references contribute to the plot without getting in the way.

Monday, November 21, 2016

The first Tess Monaghan

Laura Lippman has written a dozen Tess Monaghan mysteries. I had read a couple of them with pleasure, but I was eager to read the very first in the series, Baltimore Blues, published in 1997. It reveals how Tess, like Lippman herself a former Baltimore newspaper reporter, becomes a private investigator.

It's not by design. Having lost her reporting job when her newspaper folded, she works part-time in her Aunt Kitty's bookstore and looks around for a new job, maybe a new career. Then her workout buddy Rock offers to pay her to follow his girlfriend, Ava Hill, who has been acting strange lately. It seems like easy work, but Tess's efforts end up getting Rock accused of murdering a lawyer she suspects of having an affair with Ava. Then Rock's lawyer hires Tess to work for the defense team with some investigative work, to play Paul Drake to his Perry Mason.

Tess turns out to be a better detective than she thought at first, although still not good enough to actually solve the case until the killer, thinking she knows more than she actually does, comes after her.

Despite the ending, something of a cliche in detective fiction, Baltimore Blues makes enjoyable reading. The characters, especially Tess Monaghan, are vividly drawn, the story moves at a steady pace and the side stories actually add interest rather than seeming like filler. So I'm glad I sought out Baltimore Blues. Now I must find a copy of Charm City.

It's not by design. Having lost her reporting job when her newspaper folded, she works part-time in her Aunt Kitty's bookstore and looks around for a new job, maybe a new career. Then her workout buddy Rock offers to pay her to follow his girlfriend, Ava Hill, who has been acting strange lately. It seems like easy work, but Tess's efforts end up getting Rock accused of murdering a lawyer she suspects of having an affair with Ava. Then Rock's lawyer hires Tess to work for the defense team with some investigative work, to play Paul Drake to his Perry Mason.

Tess turns out to be a better detective than she thought at first, although still not good enough to actually solve the case until the killer, thinking she knows more than she actually does, comes after her.

Despite the ending, something of a cliche in detective fiction, Baltimore Blues makes enjoyable reading. The characters, especially Tess Monaghan, are vividly drawn, the story moves at a steady pace and the side stories actually add interest rather than seeming like filler. So I'm glad I sought out Baltimore Blues. Now I must find a copy of Charm City.

Friday, November 18, 2016

Where do writers come from?

The best American writers have come from the hinterlands -- Mark Twain, Theodore Dreiser, Jack London, Hemingway, Faulkner, Wolfe, Steinbeck. Most of them never even went to college.

The title of Edward Abbey's last book, written or rather compiled at the end of his life, is more than a metaphor, He spent much of his life in the wilderness of the American West. He had an aversion to citified, over-educated people, so it was perhaps natural that he admired those American writers who were more rural than urban, more self-educated than college-educated.

But was he right? Do the best writers come from the hinterlands? Have the best writers avoided college? He compiled quite a list of great American writers, but one could also compile an impressive list of great American writers who grew up in cities like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles and who attended college and, in some cases, taught college courses.

What Abbey perhaps should have said is that where one is from or how much education one has received has nothing, or virtually nothing, to do with writing talent. Either you've got it or you don't.

To pay the bills, many gifted writers teach college creative writing classes. These classes may help talented students become better writers, mostly by giving them incentive to actually write and then giving them feedback on what they have written. But if you can't write well on the first day of class, chances are you are still not going to be able to write well on the last day of class.

Because great writers are born, not made, they are likely to be born anywhere. At the time the writers on Abbey's list were born, there were probably more Americans born in rural areas than in urban areas. So that's where most of the best writers came from. Today more babies are born and raised in cities, so most great writers living today and in the future will probably be more urban. Also, more young people attend college today than at the time Twain, London, Faulkner, etc., lived. So more writers are going to be college-educated.

All of this means nothing. Great writers can show up anywhere at anytime. They probably should learn to read and write at some point, but after that, education doesn't matter much either.

Edward Abbey, A Voice Crying in the Wilderness

But was he right? Do the best writers come from the hinterlands? Have the best writers avoided college? He compiled quite a list of great American writers, but one could also compile an impressive list of great American writers who grew up in cities like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles and who attended college and, in some cases, taught college courses.

What Abbey perhaps should have said is that where one is from or how much education one has received has nothing, or virtually nothing, to do with writing talent. Either you've got it or you don't.

|

| Thomas Wolfe |

Because great writers are born, not made, they are likely to be born anywhere. At the time the writers on Abbey's list were born, there were probably more Americans born in rural areas than in urban areas. So that's where most of the best writers came from. Today more babies are born and raised in cities, so most great writers living today and in the future will probably be more urban. Also, more young people attend college today than at the time Twain, London, Faulkner, etc., lived. So more writers are going to be college-educated.

All of this means nothing. Great writers can show up anywhere at anytime. They probably should learn to read and write at some point, but after that, education doesn't matter much either.

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

When the lights go out

For the most part, public reaction to the possibility of a massive cyberattack has not even risen to the level of apathy.

A power outage lasting a few minutes or even a couple of hours can be an annoyance or an inconvenience. It might even be fun lighting candles and sitting together in the dark for a short time. I recall one outage that served as a nice excuse to take my wife out of town for dinner. But what if the power went out over a large, multi-state area for weeks, even months. How would most of us -- dependent upon electric power for staying warm (or cool), preparing food, doing our jobs and communicating -- survive? Imagine the chaos. Imagine the potential for violence. Imagine the suffering and death.

Ted Koppel does more than imagine all this in his new book Lights Out. He asks the tough questions, often of those in the energy industry and government who have yet to take such questions seriously.

Koppel refers to the Internet as "a weapon of mass destruction." Already, we know, hackers in Russia, China, North Korea, Iran and elsewhere have created havoc downloading supposedly secure files and shutting down websites. It may only be a matter of time before someone manages to shut down a massive power grid. Why fly airliners into skyscrapers when terrorists can do so much more damage a half a world away just by punching in the right code on a keyboard? It is only a matter of figuring out how to do it.

The energy companies, still largely self-regulated, continue to give a higher priority to profit than security, the author says. Meanwhile Congress, bogged down in politics, has other priorities, as well. Writes Koppel, "the individual can't do anything and the government won't do anything."

Actually there is something the individual can do. So far, those self-reliant folks in places like Wyoming and members of the Mormon church are the best prepared, not because they expect terrorists to cut off their power but just because being ready for disaster is what they do. Koppel devotes three of 20 chapters to the Mormon practice of stockpiling enough food and other supplies to last a year.

It's an example most of us could follow if we would only buy a little extra food and other supplies during each trip to the market and store it under beds and behind sofas. If the lights ever do go out like Ted Koppel warns us they will, such stockpiles could save our lives.

Ted Koppel. Lights Out

A power outage lasting a few minutes or even a couple of hours can be an annoyance or an inconvenience. It might even be fun lighting candles and sitting together in the dark for a short time. I recall one outage that served as a nice excuse to take my wife out of town for dinner. But what if the power went out over a large, multi-state area for weeks, even months. How would most of us -- dependent upon electric power for staying warm (or cool), preparing food, doing our jobs and communicating -- survive? Imagine the chaos. Imagine the potential for violence. Imagine the suffering and death.

|

| Ted Koppel |

Koppel refers to the Internet as "a weapon of mass destruction." Already, we know, hackers in Russia, China, North Korea, Iran and elsewhere have created havoc downloading supposedly secure files and shutting down websites. It may only be a matter of time before someone manages to shut down a massive power grid. Why fly airliners into skyscrapers when terrorists can do so much more damage a half a world away just by punching in the right code on a keyboard? It is only a matter of figuring out how to do it.

The energy companies, still largely self-regulated, continue to give a higher priority to profit than security, the author says. Meanwhile Congress, bogged down in politics, has other priorities, as well. Writes Koppel, "the individual can't do anything and the government won't do anything."

Actually there is something the individual can do. So far, those self-reliant folks in places like Wyoming and members of the Mormon church are the best prepared, not because they expect terrorists to cut off their power but just because being ready for disaster is what they do. Koppel devotes three of 20 chapters to the Mormon practice of stockpiling enough food and other supplies to last a year.

It's an example most of us could follow if we would only buy a little extra food and other supplies during each trip to the market and store it under beds and behind sofas. If the lights ever do go out like Ted Koppel warns us they will, such stockpiles could save our lives.

Monday, November 14, 2016

Authors by the score

It's not every day one gets the chance to see, hear and even speak with any of dozens of authors, but that has been my good fortune two Saturdays in a row. On Nov. 5 I attended the Buckeye Book Fair in Wooster, Ohio, where numerous writers with Ohio connections sat in large rooms to sign books, greet fans and attempt to recruit new readers. A week later I was at the Tampa Bay Times Festival of Reading at the University of South Florida in St. Petersburg, where writers, most of them with Florida connections, lectured at eight different locations across the campus.

I passed up such notables as Michael Connelly, Brad Meltzer, Joyce Maynard, Robert Olen Butler, Michael Koryta, Ace Atkins and Tim Dorsey, opting instead to listen to novelists Caroline Leavitt and Amor Towles. Years ago I read and reviewed Leavitt's novel, Into Thin Air, but I have yet to read either of the novels by Towles. I think I may give A Gentleman in Moscow a try, however, for it sounds intriguing. Here is a bit of what these two writers had to say.

"We have come to expect more accuracy from our novelists than our presidential candidates," Towles said. He may have been joking, but the timely comment seemed right on just a few days after two blatant liars each received millions of votes. Towles said any variation from historical fact in his novels draws comment from his readers, yet historical fact is not his objective. "I'm not a historical novelist," he said. "I'm a novelist." He tells stories that may be set in a particular time and place, but these stories are intended only as fiction, not reality.

Towles said his practice in writing both Rules of Civility and A Gentleman in Moscow was to write the first draft while doing doing virtually no research. Then he did whatever research was necessary to add detail and correct any blatant errors. Other writers may devote months or even years to research before even starting to write.

As for Caroline Leavitt, she spoke about how an early novel, the one I read, was successful and how she thought she was on her way. Then novel after novel failed, not necessarily because the books were bad but because publishers went out of business and editors left for other jobs. Finally she signed a contract with Algonquin and has had a string of best-sellers, including her latest, Cruel Beautiful World.

Leavitt's talk was inspirational, along the lines of, "You can do anything you want to do as long as you never give up." She seemed a little disappointed there were not more frustrated writers there for her to inspire.

Regarding her latest book, the most interesting thing she said, something I had never heard before, was that Charles Manson, yes that Charles Manson, co-wrote one of the songs on a Beach Boys album. Now she is a writer who does research.

I passed up such notables as Michael Connelly, Brad Meltzer, Joyce Maynard, Robert Olen Butler, Michael Koryta, Ace Atkins and Tim Dorsey, opting instead to listen to novelists Caroline Leavitt and Amor Towles. Years ago I read and reviewed Leavitt's novel, Into Thin Air, but I have yet to read either of the novels by Towles. I think I may give A Gentleman in Moscow a try, however, for it sounds intriguing. Here is a bit of what these two writers had to say.

"We have come to expect more accuracy from our novelists than our presidential candidates," Towles said. He may have been joking, but the timely comment seemed right on just a few days after two blatant liars each received millions of votes. Towles said any variation from historical fact in his novels draws comment from his readers, yet historical fact is not his objective. "I'm not a historical novelist," he said. "I'm a novelist." He tells stories that may be set in a particular time and place, but these stories are intended only as fiction, not reality.

Towles said his practice in writing both Rules of Civility and A Gentleman in Moscow was to write the first draft while doing doing virtually no research. Then he did whatever research was necessary to add detail and correct any blatant errors. Other writers may devote months or even years to research before even starting to write.

|

| Caroline Leavitt |

Leavitt's talk was inspirational, along the lines of, "You can do anything you want to do as long as you never give up." She seemed a little disappointed there were not more frustrated writers there for her to inspire.

Regarding her latest book, the most interesting thing she said, something I had never heard before, was that Charles Manson, yes that Charles Manson, co-wrote one of the songs on a Beach Boys album. Now she is a writer who does research.

Thursday, November 10, 2016

The democracy of time

There are only two kinds of books -- good books and the others. The good are winnowed from the bad through the democracy of time.

I like Edward Abbey's phrase "the democracy of time." America just elected its next president. Some folks are celebrating, while others are protesting in the streets. But it will be years, even decades, before "the democracy of time" determines whether the choice made by voters on Tuesday was a good one or a bad one. Abraham Lincoln is today almost universally regarded as a great president, yet at the time he was a controversial figure. It takes time to look at things objectively.

So what about books? Does the same rule apply? Probably so. Herman Melville's Moby-Dick drew scant attention when Melville was still alive. Today it is regarded as a classic. Meanwhile, most bestsellers fade from view within a few years. Does anybody still read The Bridges of Madison County?

Yet I am not so sure "the democracy of time" is always right, any more than the democracy of the ballot box or the bestseller list is. Sometimes outstanding books are ignored when they are first published and are still ignored 50 or 100 years later. Some books that are bestsellers today may deserve to still be bestsellers decades from now.

Abbey himself seemed to be of two minds on this question. In the same book he writes, "Books are like eggs -- best when fresh," suggesting that new books, not those that have stood the test of time, are the ones to read. He also wrote, "Most of the literary classics are worth reading, if you've nothing better to do," suggesting that those books deemed great through "the democracy of time" aren't really all that great.

Edward Abbey, A Voice Crying in the Wilderness

|

| Edward Abbey |

So what about books? Does the same rule apply? Probably so. Herman Melville's Moby-Dick drew scant attention when Melville was still alive. Today it is regarded as a classic. Meanwhile, most bestsellers fade from view within a few years. Does anybody still read The Bridges of Madison County?

Yet I am not so sure "the democracy of time" is always right, any more than the democracy of the ballot box or the bestseller list is. Sometimes outstanding books are ignored when they are first published and are still ignored 50 or 100 years later. Some books that are bestsellers today may deserve to still be bestsellers decades from now.

Abbey himself seemed to be of two minds on this question. In the same book he writes, "Books are like eggs -- best when fresh," suggesting that new books, not those that have stood the test of time, are the ones to read. He also wrote, "Most of the literary classics are worth reading, if you've nothing better to do," suggesting that those books deemed great through "the democracy of time" aren't really all that great.

Wednesday, November 9, 2016

Buried secrets

Buried secrets are brought to light in Silence of the Grave, one of the early entries in Arnaldur Indridason's successful series of Icelandic mysteries.

A skeleton is found after, shockingly, a little boy is seen teething with a human finger bone. The skeleton, discovered with one hand reaching up as if reaching from the grave, appears to have been in the ground for decades. It also gives the appearance of murder.