Are subtitles really necessary?

Good question.

When it comes to fiction, the answer is clearly no. A number of famous novels have had subtitles that have been all but forgotten. Thomas Hardy called his classic novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles: A Pure Woman. Nobody uses the subtitle when discussing the book. I would even call the subtitle a mistake. Let the reader decide whether Tess is a pure woman or not. Kurt Vonnegut called his famous novel Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade. Again the subtitle has been mostly ignored, although it does give scholars something to write about.

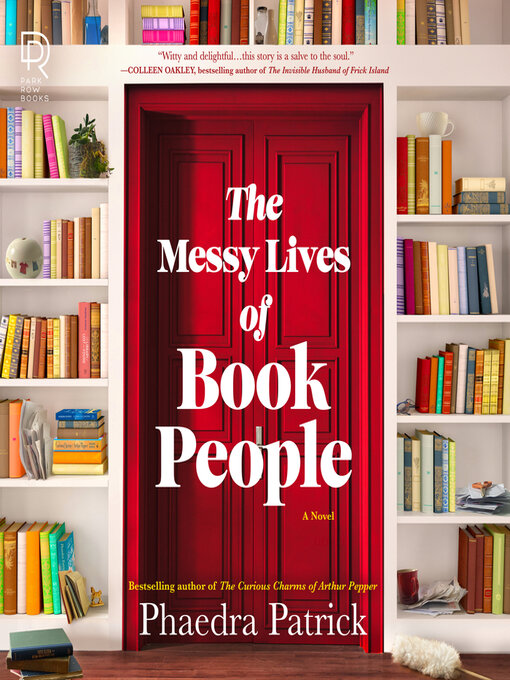

And of course the original title of Robinson Crusoe is The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner: Who lived Eight and Twenty Years, all alone in an un-inhabited Island on the Coast of America, near the Mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, wherein all the Men perished but himself. An Account how he was at last as strangely deliver'd by Pyrates. Written by Himself. Who needs all that?Most novels published today have the same subtitle: A Novel. It's not really a subtitle, of course, yet it is found under the title of most novels, letting readers know that they are holding fiction in their hands. That may not be necessary, but I am grateful for those words sometimes when it would not otherwise be clear if a book is a novel, a memoir or something else.

Subtitles are much more common in nonfiction, and for good reason. Nonfiction titles are often clever, but ambiguous. The subtitle usually gives a clearer picture of what the book is actually about. In that sense, it is a good thing.

The Great Bridge by David McCullough, which I reviewed here two days ago, carries the subtitle: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge. For those who do not recognize the bridge in the cover illustration, that subtitle serves a valuable purpose.

When biographies don't include the name of the subject in the title, a subtitle seems necessary. For example: American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell. That subtitle, in fact, seems more necessary than the title. When the subject's name is in the title, biographers often use the standard subtitle A Life, which serves much the same purpose as A Novel.

Objects of Our Desire makes a provocative title, but what is the book about? The subtitle gives us a better, if still obscure, idea: Exploring Our Intimate Connections with the Things Around Us.

When Witold Rybczynsi wrote City Life, he didn't think a subtitle was necessary. The two words in the title tell us enough, he apparently thought, although at first glance the book might be taken as a novel.

For most nonfiction books, subtitles are all but essential.