Transporting Africans to work as slaves in the American South and elsewhere was bad enough, but turning them into slaves in their own native land may have been even worse. Slave owners in Georgia or Mississippi at least had an incentive to keep their slaves alive and healthy because it cost money to replace them. When colonialists in Africa needed more workers, however, they just went out and captured them - or captured women and children to force men to work until they dropped from exhaustion.

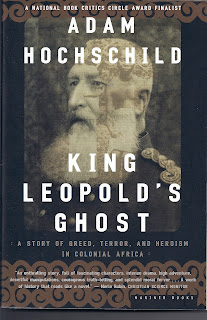

Transporting Africans to work as slaves in the American South and elsewhere was bad enough, but turning them into slaves in their own native land may have been even worse. Slave owners in Georgia or Mississippi at least had an incentive to keep their slaves alive and healthy because it cost money to replace them. When colonialists in Africa needed more workers, however, they just went out and captured them - or captured women and children to force men to work until they dropped from exhaustion.Through trickery and the expenditure of relatively little money, Leopold soon claimed ownership of the vast Congo. It wasn't actually Belgium's colony. It was his own, and all revenue from the colony went into his own pocket, even though he used the Belgian army to enforce his will there. He never visited the Congo himself.

First the colony produced large quantities of ivory, but the real wealth came from rubber. Rubber plants grew wild in the Congo. It just required someone to find those plants and harvest them. That arduous task was given to African workers, who were each given large quotas to fill if they valued their lives. Thousands upon thousands died, either from overwork or from murder.

For most of his life, ironically, King Leopold enjoyed a reputation for fighting against slavery. What he actually opposed was Arab slavery. He certainly had no objection to enslaving Africans himself, and he continued this brutal policy for decades. Mostly this was done in secret, although gradually over the years the secret began to leak out. Joseph Conrad wrote about it in his novel Heart of Darkness, missionaries told gruesome stories and a few journalists and crusaders worked hard to tell the truth to the world.

Yet even today, especially in Belgium, little is known about this sorry episode in history, although Hochschild's book has done much since 1998 to get the word out.

No comments:

Post a Comment