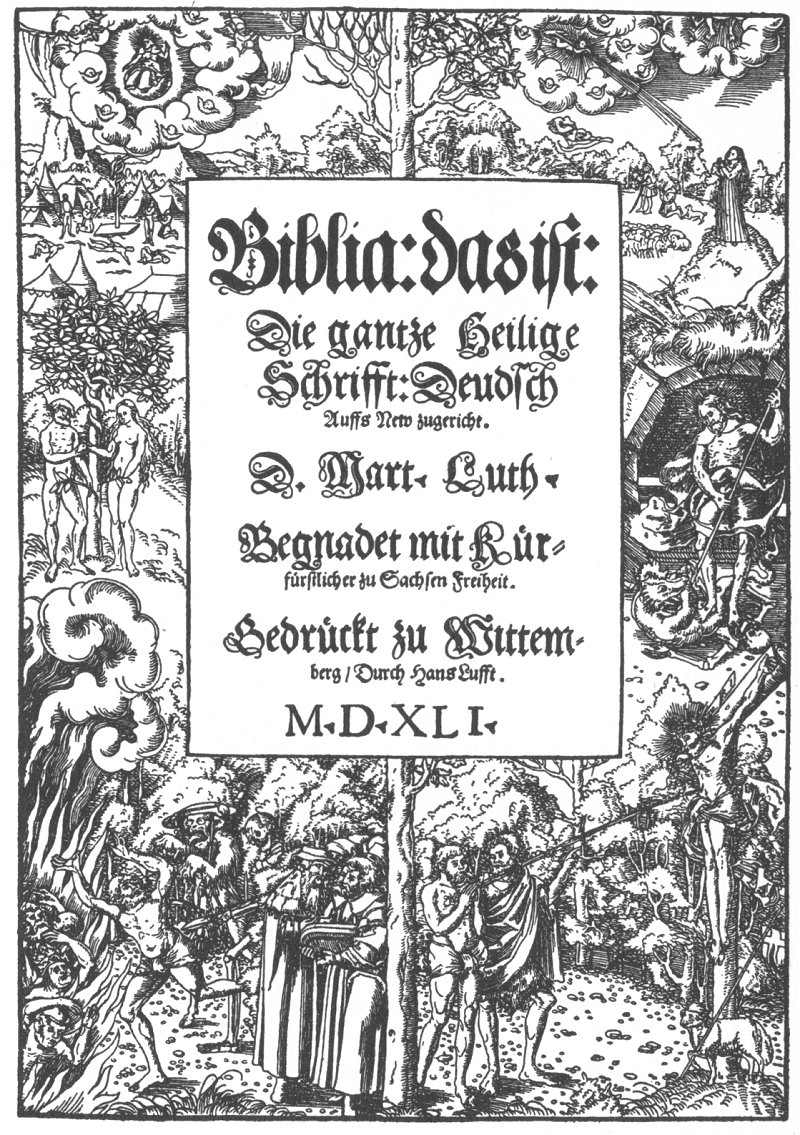

"The Luther Bible was to the modern German language what the works of Shakespeare and the King James Bible were to the modern English language. Before Luther's Bible, there was no unified German language."

"The Luther Bible was to the modern German language what the works of Shakespeare and the King James Bible were to the modern English language. Before Luther's Bible, there was no unified German language."Some might argue this was not necessarily a good thing because it led to the loss of many German dialects, and by unifying the language it unified the German people, perhaps contributing to two world wars that would follow many years later. Yet I think it's important to recognize how important the Bible has been in giving people around the world in giving people a written, unified language.

I know a man, once a guest in my home, who worked for many years among the Mam Indians in Guatemala, whose language had never been written down and was in danger of being driven to extinction by the dominant Spanish is that country until he began his work there in the 1970s. Publishing a Bible in the Mam language was among his first objectives.

"A demon always resides in the written word."

The above were the words of some German Christians, Nazi sympathizers, who first tried to remove "Israelite elements," such as the words Jehovah and Hosanna, from hymns, and later from the Bible itself. They sought a Christianity free of all Jewish influences, which turned out not to be possible. The demon, history demonstrated, resided elsewhere.

"Von Moltke and Bonhoeffer met for the first time during their trip to Norway, which had recently been handed over to Hitler by the Nazi collaborator Vidkun Quisling, whose surname became an improper noun, meaning 'traitor.'"

"Von Moltke and Bonhoeffer met for the first time during their trip to Norway, which had recently been handed over to Hitler by the Nazi collaborator Vidkun Quisling, whose surname became an improper noun, meaning 'traitor.'"I hadn't realized the origin of the word quisling was so recent.

"The next day, April 8, was the first Sunday after Easter. In Germany it is called Quasimodo Sunday."

No, Quasimodo Sunday was not named after Victor Hugo's hunchback of Notre Dame. Rather the character was born on the first Sunday after Easter and so was named Quasimodo. This word, Metaxas explains in a footnote, comes from two Latin words, quasi (meaning "as if") and modo (meaning "in the manner of"). The idea comes from the first words of I Peter 2:2, "as newborn babes," suggesting that for Christians, Easter represents a fresh start.

No comments:

Post a Comment