Joan Didion

|

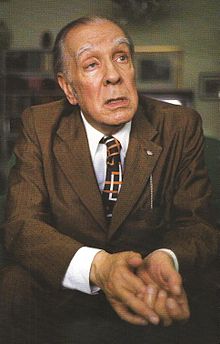

| Borges |

I never realized this was a sensitive issue with some writers until I heard novelist Ann Patchett speak at Kenyon College a couple of weeks ago. She made it clear that, for better or worse, she writes her own stories. Her characters are her own creation and they speak only the words she puts into their mouths.

I have since found a couple of quotations from other writers who, more heatedly, say much the same thing.

John Cheever said, "The legend that characters run away from their authors -- taking up drugs, having sex operations, and becoming president -- implies that the writer is a fool with no knowledge or mastery of his craft. The idea of authors running around helplessly behind their cretinous inventions is contemptible."

Vladimir Nabokov put it this way, "The trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is a old as the quills. My characters are galley slaves."

During her Kenyon lecture, Patchett rebelled against another notion that someone or something other than the author might be responsible for the final product. She told the story, also told by novelist Elizabeth Gilbert, about the time the two of them, close friends, were discussing works in progress. Patchett was at that time working on State of Wonder, and Gilbert mentioned she had abandoned her own novel set in the Amazon. When Patchett asked what Gilbert's story was about, Gilbert outlined a plot eerily similar to Patchett's own, about a medical researcher in Minnesota, having an affair with her boss, who must travel to the Amazon.

Gilbert's explanation for this uncanny coincidence was that good ideas travel around the globe looking for receptive minds to bring them to fruition. The Amazon idea first landed on Gilbert, who ultimately rejected it. So the idea moved on to Patchett, who turned it into a great novel.

Patchett cannot explain how she and her friend both had the same idea, but she finds Gilbert's explanation silly. If two people have the same idea at the same time, perhaps it is "an incredibly banal idea," she thought at the time. That can sometimes be true. I recall that back in the early Seventies, two novels about fires in skyscrapers came out at about the same time. They were The Tower by Richard Martin Stern, which I reviewed at the time, and The Inferno, by Thomas M. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson. The two novels were later combined into one movie, The Towering Inferno, which won some Oscars.

In science and discovery it is not that unusual for ideas to strike different people at the same time, as in the case of the invention of the telephone and the theory of evolution. Even so, Patchett and Gilbert both conceiving the same plot for a novel does seem astounding. Perhaps suggesting that ideas travel through space looking for a home, like believing characters write the story themselves, is just a way of explaining the unexplainable.

No comments:

Post a Comment