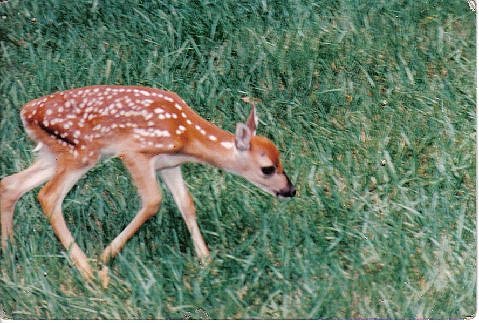

While driving through Oak Openings Park in northwestern Ohio a few weeks ago, I saw a deer by the side of the road. I stopped, expecting the deer to run, either across the road or back into the woods. Instead it just stood there. Then I noticed a tiny fawn standing behind it on unsteady legs. It looked like it may have been born just minutes before. I waited, and eventually the deer walked slowly across the road with the fawn wobbling behind, and they disappeared into the woods.

One of my dictionaries, the Oxford American, defines instinct as "an inborn impulse or tendency to perform certain acts or behave in certain ways." So perhaps it was instinct that caused that deer to move slowly across that road, when its normal instinct might have been to run in the presence of humans and their cars. And perhaps it was instinct that enabled that fawn to walk so soon after birth and to run soon thereafter.

We often think of instincts as something animals possess, not something humans have, too. In his book The Language Instinct, Steven Pinker argues that language, as his title suggests, is a human instinct. Not that we are born able to talk, as a deer is born able to walk. We do have to learn a language and a vocabulary, but we are born, he says, with the ability to use a language, any language, once we learn the basics.

As evidence he points to a typical three-year-old, whom he describes as "a grammatical genius -- master of most constructions, obeying rules far more often than flouting them, respecting language universals, erring in sensible, adultlike way, and avoid many kinds of errors altogether." He observes that children of this age are incompetent at most things, including activities seemingly less difficult than using proper grammar. Yet they can quickly learn to speak the most difficult languages, something most adults cannot do.

Pinker goes on to point out that human infants are born before their brains are fully developed, otherwise their heads would not be able to pass through the mother's pelvis. "If human beings stayed in the womb for the proportion of their life cycle that we would expect based on extrapolation from other primates, they would be born at the age of eighteen months," he says. "That is the age at which babies in fact begin to put words together." So just as that fawn could walk from the time of its birth, so in one sense, human babies can talk from the moment of theirs.

No comments:

Post a Comment