|

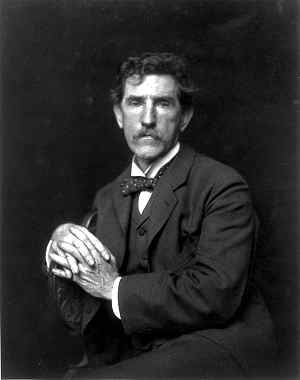

| Augustus Saint-Gaudens |

The answer to my question soon became evident. Washburne, who served in Paris during very turbulent times in the mid-19th century, kept a detailed journal in which he wrote about those times and his own significant role. Saint-Gaudens and, to a greater degree, his wife wrote excellent letters, which survive and provide great source material for any historian or biographer. Sargent and Cassatt apparently wrote less about their own lives, giving future scholars less to write about. What McCullough says about Sargent mostly comes from what friends and art critics said about him.

Winston Churchill was a great man, but I wonder if those long, in some cases multi-volume, biographies of his life are partly due to the fact that he wrote so much about himself, giving his biographers more material than they can fit into a single volume. Meanwhile, William Shakespeare, for all the great plays and sonnets he left behind, apparently wrote little about himself, giving biographers next to nothing to work with.

|

| Mary Chestnut |

Moving closer to home, if you should happen to discover a diary kept by your great-grandmother, or perhaps letters she wrote to a friend over decades, you will know much more about her life than that of any of your other great-grandmothers. Leaving a written record of your life, even if it's nothing more than writing your own obituary and putting it where your children will find it, improves the odds that you and your accomplishments will be remembered.

I wonder about historians and biographers of the future. Will e-mails, texts, blogs and Facebook pages, if they are even available for study, provide the same kind of source material that letters and diaries provide?

No comments:

Post a Comment