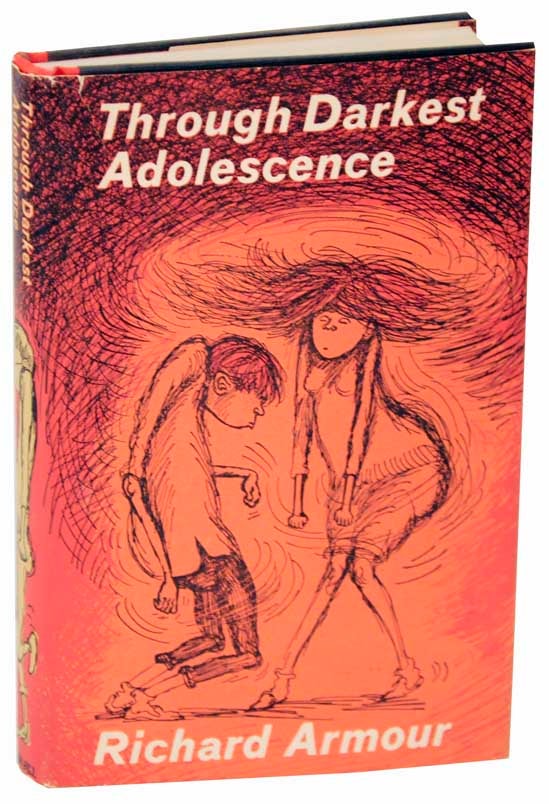

I was quite a number of pages into Through Darkest Adolescence, Richard Armour's comical lament about raising teenagers, before I realized that, since the book was published in 1963, I myself was one of those teenagers in question. From then on the book became a little more personal, even a little more amusing.

Armour is at his best in the opening chapter where he discusses adolescence as a disease, a disease that is not contagious and that you get only once, although it can hang on for several years. For a few people, he warns, it can last much longer, as among those people who act like teenagers well into middle age. After writing about some of the more serious symptoms of this disease, he concludes, "Some day a Dr. Salk will probably come along with a vaccine for adolescence. If so, the only question will be which Nobel Prize he should get -- the one for medicine or the one for peace."

From there, he moves on to such topics as getting a chance at the bathroom when there are teens in the house, teen parties, what to do when your kids are old enough to drive and problems related to cutting hair and straightening teeth. He uses his own son and daughter as examples, which must have embarrassed them terribly. However, since he was born in 1906, his kids may have been well into adulthood by 1963.

Armour wrote light verse to rival that of his contemporary, Ogden Nash. Unfortunately some of his poems are often wrongly attributed to Nash. We get a nice sampling of his verse scattered throughout this book. Here is one example:

We've only a teen-age daughter,

A two-legged creature indeed,

And yet from the shoes

She incessantly strews,

You'd think we've a centipede.

Armour's wit seems to fail him late in his book when he addresses the subjects of smoking and drinking. His strategy for discouraging these behaviors is to encourage his kids to smoke cigars and consume large quantities of alcohol on the theory that after this they will not want to smoke or drink at all. Of course, this strategy fails. None of this misbehavior, and I'm referring to that of the parent, seems funny now, and I doubt that it was funny even in 1963.

However I do recall that when I was a little boy my father offered me a sip of his beer. I cried loudly at the taste, and my mother came running from the kitchen, giving Dad a firm lecture when she found out what had happened. But I have never wanted a beer since. So maybe Armour's strange strategy might have worked if he had only tried it a decade earlier.

No comments:

Post a Comment