Three of the 19 chapter titles in Peter Padfield's new book Night Flight to Dungavel: Rudolf Hess, Winston Churchill, and the Real Turning Point of WWII take the form of questions. Two others contain the word question. In truth, the entire book asks more questions than it answers.

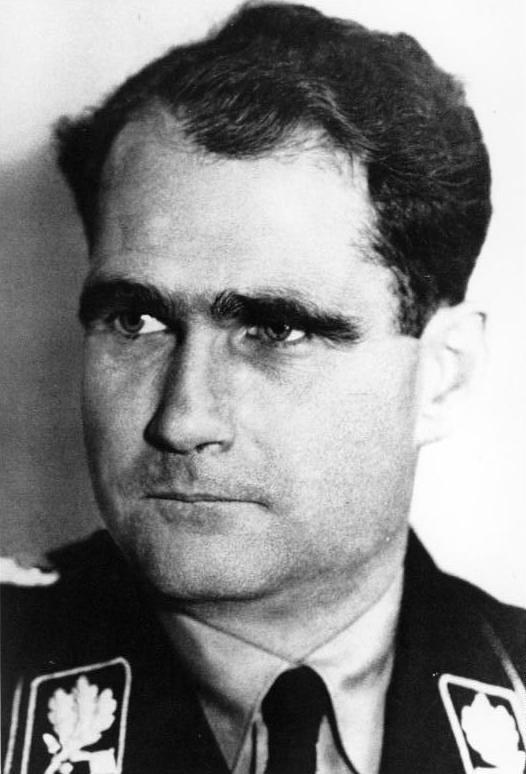

Why did Rudolf Hess, one of Hitler's top deputies, make a solo flight to Scotland in May of 1941? Was he really trying to negotiate a peace as he claimed? Did Hitler know about and approve his flight ahead of time? Did Prime Minister Winston Churchill know about it ahead of time? Did the British trick Hess into making the flight in the first place? Why was Hess kept prisoner until his death in 1987 long after Nazis convicted of greater war crimes had been released? Did he, a feeble 93-year-old, really die by his own hand? Or was he murdered as some evidence suggests? But if so, why and by whom?

Padfield asserts, as other historians have done, that Hitler did not really want a war with Britain. His goals were capturing a large chunk of Europe and thwarting the Communists to the east of Germany. There were many in Britain in 1941 who would have gladly accepted peace terms with Germany at this point, but Hitler did not count on Churchill, who was determined to resist the Nazis even if Britain had to do it alone. Hess apparently flew to Scotland hoping to contact high-ranking appeasers who might be able to overthrow Churchill and take control of the British government, then make peace on Germany's terms.

But why keep it all a secret to this day? Presumably the secrets, if revealed, would in some way blemish Britain's glorious history. Might members of British royalty, who after all came from Germany in the first place, have been among those striving to make peace with Hitler? Might Hess have revealed to the British government details about the planned mass extermination of European Jews that Churchill, for whatever reason, kept to himself?

A reader should not blame Padfield for not answering all the questions he asks in his book. Until the British government spills its secrets, no one will be able to answer these questions with any certainty. But the author might have presented the questions with more clarity than he does. During the middle part of the book he buries the reader in details that, for the ordinary reader at any rate, reveal little of interest. The best chapters are those at the beginning, where Padfield tells what is known about Hess's death, and the latter chapters, where he sums up and speculates about possible answers to many of these lingering questions.

No comments:

Post a Comment