Darrin Lunde,

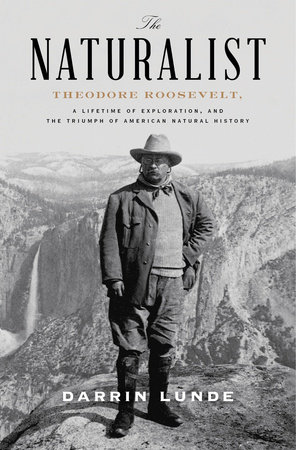

The Naturalist: Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of American Natural History

For a number of years I was a member of the Audubon Society by reason of subscribing to the magazine. I identified the group with protecting the environment and all forms of flora and fauna. I identified them with their annual bird count, as well. I recall then being a bit shocked when I read in a biography of James J. Audubon about how many birds he killed in his search for a few good specimens to mount as models for his paintings. The man we most identify with American birds slaughtered those birds in large numbers?

Lunde explains that the study of animals once meant killing them. Today scientists use cameras to observe animals and sophisticated equipment to track them and study them without actually harming them. Times had already begun to change during Roosevelt's time, slightly more than a century ago. His hunting practices were controversial even then, which is why he hunted very little as president. He left the White House, rather than seek another term, because he wanted to hunt big game in Africa.

Roosevelt loved outdoor adventure and he loved hunting. Because of his poor eyesight, he was a poor shot and did best when hunting large animals. It often took him numerous shots to down an animal, although that was partly due to the fact that he favored a less powerful gun than was ideal. Lunde doesn't whitewash any of this, but he does make the case that Roosevelt was also committed to natural history and to natural history museums, such as the Smithsonian. When he hunted, he usually sent the best specimens back to these museums in New York and Washington. If you visit them today you can still see some of the animals Teddy Roosevelt killed in Africa and in the American West.

Yet when he knew certain species were endangered, such as the American bison and the African elephant and white rhino, he was all the more determined to kill them while there were still some to kill, and not just so their carcasses could stand in museums. He yearned to hunt and kill them while he could. Lunde says Roosevelt killed five northern white rhinos, while his son, Kermit, killed four. "Most were shot as they rose from slumber."

When people talk about Theodore Roosevelt the naturalist today, they usually focus on his creation of national parks and wildlife areas when he was president. They say less about the rest because, if it was controversial a century ago, it is much more so today.

Lunde begins his book by explaining what he and Roosevelt have in common. They both grew up in New York City where they developed a keen interest in natural history. Both hunted and studied taxidermy. Both collected for museums. "Roosevelt and I may have both sought adventure, but our pursuit is no less real or sincere than that of a traditional scientist in a lab coat," he writes.

No comments:

Post a Comment